Could anything have checked America’s mad rush to war in Iraq in 2003, driven as it was by a cabal of neoconmen intent on cynically manipulating the trauma of 9-11 to achieve a different agenda?

Perhaps (1) if Colin Powell had the courage to resign on principle rather than allowing himself to be pressured into giving his disgraceful imitation of Adlai Stevenson's performance at the UN during the Cuban Missile Crisis, or almost certainly (2) if the UK Prime Minister Tony Blair sided with France, Germany, and Russia and the majority of Europeans in opposing the Iraq war. Of course, no one will ever know, but Powell enjoyed immense moral stature at the time, and without his cheerleading, the veneer of Bush’s and Cheney’s moral authority would certainly have been far weaker. The case of Blair, aka Bush’s poodle, is more complex: If the UK sided with Europe, Bush would have been isolated and the march to war very likely might well have been still born.

But a large number, perhaps a majority, of the English people do not see themselves as being Europeans. And the English elites, like Blair, trust instead in using the UK’s “special relationship” with the US to punch above their weight in world affairs. Viewed narrowly, the UK-US special relationship has roots in WWII, but the UK’s proud sense of separateness from Europe reaches back at least a 1000 years in history and is grounded in its island geography. The English have never resolved the question: Are they part of Europe? The UK’s tepid membership in the EU illustrates the point.

The below op-ed by Immanuel Wallerstein argues that European question is again coming to forefront of British politics and pressure to leave the EU is mounting. Moreover, the question is being complicated by the growing regional tensions in Northern Ireland, Wales, and especially Scotland.

One issue not addressed by Wallerstein is how the rising forces of regionalism relate to the EU vis-à-vis England. Would an independent Scotland, for example, prefer to remain in the EU for reasons of economic benefits of the free trade area, access to developmental loans, and having a hedge against English revanchism?

This is not an idle concern: If one believes the leaders of the Scottish Nationalist Party, who want to hold a referendum on seceding from the UK 2014 but have also made it clear they want an independent Scotland to remain in the EU.

My guess is that the UK will do what it does best: muddle thru. But we live in interesting times and strange things can happen.

Britain's Search for a Post-Hegemonic Identity

Immanuel Wallerstein, Agence Global, 01 Jun 2013

Once upon a time, the sun never set on the British Empire. No more! In 1945, Winston Churchill famously said: “I have not become the King's First Minister to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.” But in fact that is exactly what he did. Churchill knew the difference between bombast and power.

Ever since 1945, Great Britain has been trying, with considerable difficulty, to adjust to the role of erstwhile hegemonic power. One has to appreciate how difficult this is, both psychologically and politically. It seems today as if the dilemmas of its political strategy have finally imploded, and it is faced with choices that are all bad.

Great Britain emerged from the Second World War as one of the Big Three — the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain. It was however the weakest of the Big Three. The strategy it chose was to become the junior partner of the United States, the new hegemonic power. This was called, in Great Britain at least, the “special relationship” it claimed it had with the United States.

The most important benefit Great Britain obtained from this special relationship was the immediate transfer of nuclear technology, permitting Great Britain to be, from that point on, a nuclear power. The United States did not by any means make a similar gesture to the Soviet Union, much less to France. The United States was seeking a global nuclear monopoly shared only by its junior partner. Of course, as we know, this global monopoly was undone first by the Soviet Union, then by France and China, and then later by a number of other states.

In continental western Europe, the first steps toward Franco-German reconciliation began as the European Coal and Steel Community. It included six nations — France, Germany, Italy, and the Benelux trio of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxemburg. It did not include Great Britain. These first steps towards the European Union of today were at the time encouraged by the United States, as a mode of making possible the incorporation of the western parts of Germany into what would become the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

It is not sure that British leaders appreciated this new continental European structure. One of the ways Great Britain seemed to react was to attempt a geopolitical stance independent of the United States. It joined forces with France and Israel to attack Nasser's Egypt. The United States was pursuing at the time another strategy in the Middle East, and therefore lost no time to rap the knuckles of Great Britain and insist that it withdraw its troops. This was humiliating for Great Britain, but it also reminded them of the limits of their ability to be independent of the United States.

After this, however, the United States began to encourage Great Britain to join the continental structures. In part, this was because the United States was beginning to worry about a French-inspired relative independent position of these structures. From the U.S. point of view, Great Britain could help prevent this. Such an entry had a particular advantage from a British point of view. Great Britain's last remaining vestige of its erstwhile hegemony was the continuing major role of the City of London in world finance. Great Britain needed access to the European markets to guarantee this role.

The problem for Great Britain today is that all the choices before it are bad. Great Britain wishes to insist that it is still a major military power. But the very same government that is asserting this is also reducing expenditure upon and the size of its armed forces, as part of its austerity program.

The biggest problem for Great Britain today is that the rest of the world will simply not consider it to be a very important geopolitical and financial actor anymore. Being ignored is not the happiest fate for an erstwhile hegemonic power.

Immanuel Wallerstein, Senior Research Scholar at Yale University, is the author of The Decline of American Power: The U.S. in a Chaotic World (New Press).

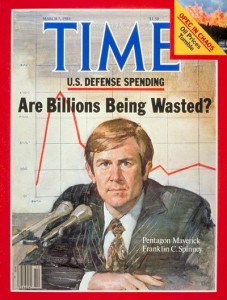

Phi Beta Iota: Yellow highlights are from Chuck Spinney. The era of empire based on lies and theater is over. Emergent is a restored era of tribalism and regionalism based on transparency, truth, and trust such as the United Nations will never achieve. NATO is at a cross-roads — if it heeds Admiral Stavrides' wisdom with respect to Open Source Security, it will embrace the BRICS and strive to create OSE?M4IS2 as a global to local model for open source everything and local to global and back multinational information sharing. More likely is that the UK and US empires will fragment rapidly over the next decade, and the BRICS will emerge as a new form of global to local hybrid “soft” empire that fully leverages the information advantage that continues to escape the US and UK.

See Also:

Multinational, Multiagency, Multidisciplinary, Multidomain Information-Sharing and Sense-Making