使用谷歌翻译在下一列的顶部。

गूगल अगले स्तंभ के शीर्ष पर अनुवाद का प्रयोग करें.

Google sonraki sütunun üstünde Çevir kullanın.

Используйте Google Translate на вершине соседней колонке.

گوگل اگلے کالم میں سب سے اوپر ترجمہ کا استعمال کریں.

National Interest, March/April 2009

Milt Bearden

Milton Bearden is a retired CIA officer who managed the cia’s covert assistance to the Afghans from Pakistan during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. He also served in Hong Kong, Switzerland, Nigeria, Sudan and Germany.

As the United States settles into its . eighth year of military operations in . Afghanistan, and as plans for ramping up U.S. troop strength are under way, we might reflect on an observation made by the Chinese military sage, Sun Tzu, about twenty-five hundred years ago:

In military campaigns I have heard of awkward speed but have never seen any skill in lengthy campaigns. No country has ever profited from protracted warfare.

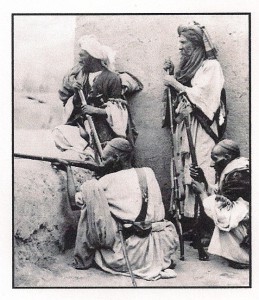

These words tell the tale of the string of superpowers that have found themselves drawn into a fight in the inhospitable terrain we now call Afghanistan. Their stories of easy conquest followed by unyielding rebellion are hauntingly similar, from the earliest accounts of Alexander’s Afghan campaign, when, in 329 bc, the great warrior found the struggle longer, more brutal and more costly than his battle in Persia. And through six centuries the Mughals never managed to bring the Afghans to heel, and most certainly not the Pashtuns. Of course, there were also the disastrous expeditions of Britain and the Soviet Union. Now it is up to the Obama administration to try to change the long odds in what will become America’s longest war.

Perhaps the failure of empires in Afghanistan is merely destiny. Each has largely made the same mistakes as its forebears, above all underestimating the Afghans. The premier historian on Afghanistan, the late Louis Dupree, explained how the occupation of Afghan territory by foreign troops, the placing of an unpopular emir on the throne, the harsh acts of occupier-supported segments of the Afghan population against their Afghan enemies and the reduction of the subsidies paid to the tribal chiefs all led to imperial demise.

The United States may not yet have reached that point where it is just another occupation force facing a generalized resistance, but it is getting close. It is, indeed, much as the Mughals who came before, facing a Pashtun insurgency in the east and south of Afghanistan, where invaders historically fail. In Hamid Karzai they have placed an unpopular leader at the helm. The ineffective U.S. aid programs have done little to subsidize potential allies. And so America finds itself pursuing the failed plan of so many ambitious states of the past.

Afghanistan, though never conquered, has rarely found itself without a potential occupier to hold at bay. And all of those empires have fallen victim to Dupree’s four banes. Alexander may have been the first to almost lose his kingdom to the Afghan battlefield, but many followed. This may be the starkest case of Obama’s need to learn from history. After centuries of unrelenting but ultimately failed attempts at conquest, early in the nineteenth century, as imperial Russia expanded its influence in central Asia and as Britain consolidated control of the Indian subcontinent, Afghanistan (much like its occupiers) found itself a victim of circumstance once again. Russia and Great Britain set themselves on a collision course. Afghanistan lay between them as the fulcrum of the “Great Game” of espionage, diplomacy and proxy conflict that would play out over the rest of the century.

The First Anglo-Afghan War of 1839–1842 sprang from British India’s need to protect its western flank. Certain that Russia intended to encroach on its empire, in December 1838 the British governor general of India declared the Russian-favored emir of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammed Khan, “dethroned,” and launched British forces into Afghanistan. Entry was easy, and after a leisurely march through Kandahar and Ghazni, British forces reached Kabul in August 1839 and placed their man, Shah Shuja, on the throne. The first fatal error.

By 1841 British forces in Afghanistan faced a murderous rebellion led by the deposed emir’s son. On January 1, 1842, three years after their invasion, a combined force of sixteen thousand five hundred British and Indian troops began its retreat from Kabul under an agreement of safe conduct. The passage was anything but safe, however, as the retreating forces came under persistent attack by Pashtun Ghilzai warriors in the snowbound mountain passes on the hundred-mile route to Jalalabad. In one of the most crushing defeats in the empire’s history, the remnants of the British column were massacred about thirty-five miles from Jalalabad. The sole survivor of the march was an army surgeon. Shah Shuja was assassinated four months later. In 1878, the British would repeat these mistakes in a brief war that would end with another humiliating defeat at Maiwand, about fifty miles northwest of Kandahar, where Afghans killed around one thousand British and Indian troops.

The Soviets would follow the failed British playbook a century later, embarking on their own Afghan adventure on Christmas Eve, 1979. Their decision to move a “limited contingent of Soviet forces” into Afghanistan was based on cooked intelligence that argued America was plotting to use Afghanistan to threaten Russia’s central-Asian republics. Really a cover-up for the Soviet Union’s own imperial agenda for Afghanistan, these claims supported the doctrines of their aging and ailing leader, Leonid Brezhnev. And so the invasion was launched. The Soviet foray was brutally efficient. The troublesome Afghan leader, Hafizullah Amin, was assassinated; Kabul was secured; and “their emir,” Babrak Karmal, was installed at the helm of the Afghan government. Another false leader placed atop the throne. It seemed easy, and it initially looked as if the politburo had called it right; they would be in and out of Afghanistan almost before anyone noticed. Certainly, President Jimmy Carter must be too preoccupied with his hostage crisis in Iran to give much thought

to Afghanistan, or so the Kremlin thinking went.

Not quite. Carter reacted decisively. He cancelled a number of pending agreements with the ussr, ranging from wheat sales to consular exchanges, set in motion the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics and quietly signed a presidential finding tasking the CIA to organize assistance, including lethal aid, to the Afghan people in their resistance to the Soviet invasion.

By the fifth year of their war, the Soviet 40th Army had grown from its original limited contingent to a countrywide occupation force of around one hundred twenty thousand troops. Again, here was an outside state foolishly attempting to occupy Afghan territory. As Soviet forces grew, so did the Afghan resistance; by the mid-1980s there were around two hundred fifty thousand full- or part-time mujahideen. Soviet efforts were beginning to falter, and, in 1986, the new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, declared Afghanistan a “bleeding wound.” He gave his commanders a year to turn it around. They didn’t, and by the end of the 1986 fighting season, the Soviet position had deteriorated further. When the snows melted in the high passes for the new fighting season of 1987, diplomatic activity intensified. A year later, on April 14, 1988, the Geneva Accords ending Soviet involvement in Afghanistan were signed. The Soviets were out of Afghanistan nine months later.

In the nine years of their Afghan adventure, the Soviet Union admitted to having lost around fifteen thousand troops killed in action, several tens of thousands wounded and tens of thousands more dead from disease. The Afghan population had suffered horrendous losses—more than a million dead, a million and a half injured, plus 6 million more driven into internal and external exile. The costs to the ussr, however, would soar with the breathtaking events that followed their February 15, 1989, retreat. In May, Hungary opened its border with Austria without fear of Soviet intervention; a month later came the election of Polish Solidarity leader Lech Walesa, bringing an end to Communist rule in Poland; throughout the summer of 1989, the people of East Germany took to the streets until, on the night of November 9, 1989, the Berlin wall was finally breached. The world had only just digested the events in Berlin when Vaclav Havel carried out his “velvet” revolution in Czechoslovakia a month later. Three hundred twenty-nine days after the Berlin wall fell, Germany was reunited inside NATO, and the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact were on deathwatch. Their Afghan campaign was indeed the death knell for the Soviet Union. But Afghanistan too would plague the United States a short time later.

Superpower stories of easy conquest in Afghanistan followed

by unyielding rebellion are hauntingly similar.

With the world’s attention focused almost entirely on the historic events in Eastern Europe, scant attention was paid to the drama unfolding in Afghanistan at the end of the cold war. There was no looking back by senior levels of the administration of George H. W. Bush. All energies were consumed by the denouement of the Soviet Union and its aftermath. The neglect would be a grave error.

No one accounted for the fact that during the Soviet occupation, the call to jihad had reached all corners of the Islamic world, attracting Arabs young and old and with a variety of motivations to take up arms against the invaders of an Islamic country. There were sincere volunteers on humanitarian missions; there were adventure seekers on paths of glory; and there were Salafist psychopaths. As the war dragged on, some Arab states emptied their prisons of their own scourges and sent them off to the Afghan jihad with the hope that they would never return. Altogether, over ten years of war as many as twenty-five thousand Arabs may have passed through Pakistan and Afghanistan.

As the 1990s began with great hope elsewhere in the world, a new post-cold-war construct took shape in Afghanistan—the failed state. Though the Soviets had quit the country in 1989, it would not be until April 1992 that the mujahideen would finally take Kabul. Almost immediately, ancient hatreds and ethnic rivalries drove events. Absent the presence of that single unifying factor that had survived the test of history—foreign armies on Afghan soil—the state failed. Intrastate conflict took on a new brutality, until the population was ready for any path to security.

Rising almost mystically from the chaos, what was soon to be America’s enemy, the Taliban (meaning Islamic students or seekers), formed under the leadership of a one-eyed cleric from Maiwand. Almost exclusively a Pashtun movement, the Taliban swept easily through eastern Afghanistan, bringing relief to the people from brigands controlling the valleys and mountain passes. By 1996, the Taliban had seized Kabul, and the Afghan people seemed to accept their deliverance. The West fleetingly saw the Taliban as a source of order and a possible tool in a modern replay of the Great Game—the race to market the energy riches of central Asia. But the optimism was short-lived, and Afghanistan continued its downward spiral as the Taliban overreached in its quest for total control of the state. The movement’s human-rights record and treatment of women drew international scorn, and with the exception of diplomatic recognition from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Pakistan, Afghanistan was in complete isolation. Its failure as a state of any recognizable form was total.

Against this failed-state backdrop, the old Afghan Arab troublemakers—who had witnessed close hand the Soviet folly in Afghanistan a decade earlier—drifted back into the country. The Arab jihadists had returned. Among them was the son of a Saudi billionaire, Osama bin Laden.

America’s fate was sealed. Bin Laden had settled in Khartoum after a failed attempt to bring about change in his Saudi homeland. It was in Sudan that he became consumed by his brooding enmity toward the United States, a hatred that had been defined by the Gulf War and the presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia. In 1996, responding to U.S. and Saudi pressure, Sudan expelled bin Laden. He moved to Afghanistan—the last stop on the terror line—where his seething hatred of the United States would take its deadly shape, first with an attack on the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and then again on September 11, 2001, in a blow of unimaginable boldness and immeasurable devastation.

The United States reeled. Four weeks later, on October 7, 2001, small contingents of CIA officers and U.S. Army Special Forces troops linked up with elements of the Northern Alliance and other Afghan anti-Taliban groups, and, supported by U.S. and British air and missile strikes, kicked off the United States’ war in Afghanistan. The response seemed right to most observers; it looked easy, even entertaining, to a stunned nation looking for payback in the early days of Operation Enduring Freedom, as the Afghan action was called. U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld became a matinee idol as he briefed the press on the U.S. operations, sometimes using romantic footage of U.S. troopers and CIA officers in cavalry charges, galloping across the Shomali Plains on Afghan ponies. An eerie repetition of history began to unfold on the fields of Afghanistan.

At the outset it was almost entirely a war prosecuted by cia paramilitary teams and special-operations forces with air support. There was little need for large-scale army or marine forces. The goals of the invasion seemed reasonable: capture or kill Osama bin Laden and other al-Qaeda players behind the attack on 9/11; remove al-Qaeda’s Taliban supporters from power; and then set things right in an Afghanistan the United States and the West had abandoned after the Soviets quit the field a dozen years earlier.

Things stayed on schedule, at first. By mid-November the Taliban had slipped out of Kabul, and Northern Alliance forces moved quickly to fill the vacuum. Within days, the Taliban was collapsing like a house of cards, and on December 7 their leader, Mullah Omar, escaped encirclement at Kandahar and withdrew to the mountains of nearby Oruzgan Province. The last Taliban-held city fell and the movement ceased to exist as a political or military force, at least for the moment. The Taliban had been dispersed in all directions.

Large numbers of the Pashtun Taliban had slipped across the Durand Line, a border between Afghanistan and Pakistan that they and their forebears had ignored. Another legacy of the violent past, it was a demarcation made by the British out of the frustration of their two failed wars against the Afghans almost a century earlier. It was a border that served the nineteenth-century needs of Great Britain, but it artificially separated the Pashtun tribes, whose numbers today total around 40 million, with about 25 million on the Pakistani side of the zero line (as the Durand Line is also called) and around 15 million on the Afghan side. The Pashtuns’ tribal linkages have always trumped the demarcation, and by the end of 2001 a reestablishment of the Pashtun safe haven in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (fata) that had so tormented the Soviets was under way.

But still the Americans were fooled into seeing an easy victory ahead. In early December 2001, the noose had tightened on Osama bin Laden at Tora Bora in the White Mountains of eastern Afghanistan near Pakistan’s Kurram Agency, one of the districts in the fata. Yet, in a sequence of events still hotly debated by those on the ground at the time, bin Laden slipped away and made his journey into Pakistan’s tribal areas. In the last seven years there have been few, if any, credible sightings of him in Afghanistan or Pakistan, though it has become conventional wisdom that he is somewhere in the fata.

The United States may not yet have reached that point

where it is just another occupation force facing a

generalized resistance, but it is getting close.

Meanwhile, a gathering of prominent Afghans was convened at the Hotel Petersberg, across the Rhine from Bonn, under the auspices of the United Nations. On December

22, 2001, an Afghan Interim Authority, comprised of thirty members, was established, with Hamid Karzai at its head. Thus, within ninety days of the terrorist attack on America, just reprisals had been seemingly executed. The Taliban had been overthrown, a ruling body for Afghanistan had been chosen, a constitution was in train, elections planned, and, we were assured, Osama bin Laden was steps away from capture or death.

It had all seemed so easy that by 2002 vital military resources were being redirected from Afghanistan to the Bush administration’s new target, Iraq.

However, the United States had committed the cardinal sins of empire. Fastforward seven tough years, and the experience of the latest superpower to venture into Afghanistan looks like that of all of those who came before. The admonition against placing an unpopular emir on the Afghan throne was breached at the outset. The “unpopular emir” cachet, in the eyes of the Pashtuns, originally fell to the Northern Alliance leaders placed in high positions in the Afghan government. While Hamid Karzai was not the “unpopular emir” at the beginning of his tenure, he is achieving that distinction now. He is viewed as able to remain in office only with U.S. protection. And then there were the harsh acts of the U.S.-supported segments of the Afghan population against their Afghan enemies, which have also worked against the United States. Tales of massacres of Pashtun Taliban prisoners in the north by our Northern Alliance allies are now part of Pashtun legend, fuelling their code of revenge. Dupree’s counsel against reducing subsidies paid to the tribal chiefs can best be understood here in the utter failure of the foreign-assistance packages for Afghanistan—of the more than $30 billion in

programmed aid, little has made it beyond the dark recesses of foreign contractors and NGOs. And of course, in the meantime, America had occupied Afghan territory.

There is an unrelenting insurgency—we call it the Taliban, though that is a dangerous oversimplification. It is in effect a Pashtun insurgency, made up of, indeed, Taliban, but also angry Pashtuns, criminal bands and paid gunfighters. Rural Afghanistan is engulfed in the opium trade, with poppy cultivation accounting for about 53 percent of the 2008 Afghan gdp, last estimated at $7.5 billion and accounting for over 90 percent of the world’s illicit heroin production. The corruption spawned by the drug trade has permeated all levels of the Afghan government, severely limiting its ability to deliver services or security even in some parts of Kabul. Most affected by the corruption may be the Afghan National Police, forcing hopes for improved security to recede even more.

Cynical Afghans derisively refer to Karzai as “the mayor of Kabul,” and whispers of his family’s involvement in the drug trade are growing louder. U.S. casualties have surged from an even dozen in 2001 to 155 in 2008. Coalition casualties have risen above one thousand. Across the zero line in Pakistan’s fata, always part of any war against the Pashtuns, conditions are dire. Islamabad is fully involved in the conflict now. fata is a war zone, with the Pakistan Army taking higher casualties than coalition forces in Afghanistan. Further afield in Pakistan, the so-called “settled areas” of the North-West Frontier Province, prominently the picturesque Swat Valley, are under mounting threat of “Talibanization,”

though in many cases the Pakistani Taliban is little more than teenage punks with guns, paid around $8 per day from drug money flowing in from Afghanistan. Attacks against U.S.- contracted convoys through Pakistan to Afghanistan have increased, blocking the flow of vital food and fuel supplies to coalition forces, and forcing the United States to seek deals with Russia and the central-Asian countries to the north of Afghanistan for alternate supply routes. It is difficult to understate the irony in that or to overestimate the potential political costs of cutting a deal with Vladimir Putin, the successor to those who launched the most recent and brutal occupation of Afghanistan, and lost their empire in the process.

Suicide bombings have killed large numbers of Pakistani civilians and senior military officers, as well as assassinating former–Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto as she campaigned for office just over a year ago. U.S. complaints that Pakistan is “not doing its part” fail to take into account that its army is organized and trained to defend against India, an adversary with which it has fought three very real wars; it is not constituted to carry out the counterinsurgency we demand. Such criticism also misses the fact that Pakistan is understandably reluctant to carry out counterinsurgency operations when doing so amounts to engaging in a civil war. Finger wagging won’t change that, particularly when most Pakistanis are convinced that it’s only a matter of time before the United States abandons them in the field once again.

So what now? The Obama administration has been quick to learn that Afghanistan is anything but “the good war.” In his earliest discussions with his military advisers, Obama has also learned that Afghanistan is not Iraq, and that neither an Iraq-style surge nor a replication of the so-called Anbar Awakening is readily transferable to Afghanistan—where the tribal structure, topography, level of education, national economy and development are totally different from conditions in Iraq. Per capita GDP in Afghanistan, at about $350, is one tenth that of Iraq; adult literacy is 25 percent compared to about 75 percent in Iraq; and the actual population pool for the Afghan insurgency spans the Durand Line and is around 40 million Pashtuns. In appointing Richard Holbrooke as his special envoy to Pakistan and Afghanistan, the president has acknowledged that the two countries are one theater of conflict. This is progress.

The Obama administration has been quick to learn

that Afghanistan is anything but “the good war.”

But the first problem with U.S. planning begins with the idea that increasing America’s military footprint is enough. Campaign rhetoric about ramping up U.S. troop presence by another three brigades is being challenged, and properly so. Former commander of the International Security Assistance Force (isaf ) in Afghanistan, General Dan McNeill, in a moment of candor last June, estimated that it would take four hundred thousand troops to pacify Afghanistan. He may have been right. And those numbers are not possible. Critics also point out that a fundamental redefinition of the mission is more important than troop numbers. If the troop increase means more of the same type of operations, there will be no advantage gained. More gunfighters means more gunfights, and there has never been evidence to suggest that outsiders can wear down an Afghan insurgency through rising body counts. Even sending in additional special-operations forces has its problems, since there is a growing recognition in military circles that any case, will be pulling out over the next two years. It should not be forgotten that the ussr maintained one hundred twenty thousand troops in Afghanistan for nearly a decade, and still lost. Perhaps Defense Secretary Robert Gates had it right when in his January 27 testimony on Capitol Hill he said that “if we set ourselves the objective of creating some sort of central Asian Valhalla over there, we will lose. . . .”

Then there is the question of how to deal with the militias. Discussion of arming Afghanistan’s militias has led to little in the way of consensus. Many Afghans and some old Afghan hands say it won’t work because it has never worked before, that it will lead to more conflict and that militias armed by outsiders can never be controlled. Others say it is worth a try. Both may be right.

The militia solution always surfaces when a foreign enterprise in Afghanistan faces failure; and, yes, militias armed by outsiders have ended up fighting each other in the past. During the 1980s militias repeatedly turned on their Soviet armorers, or otherwise betrayed them. Indeed, Soviet-armed militias in eastern Afghanistan became quartermasters for the CIA, selling their weapons to the mujahideen for hard CIA cash, while saving the CIA huge transportation costs to boot. The Soviets paid the freight.

But the United States, inevitably, will arm some militias. The question will be how many and where and how? Some recommend giving the Karzai government a hand in the process. That should be carefully thought through, as it may only end up increasing the intramural fighting. If militias must be raised, the United States had better do it in concert with traditional tribal-leadership systems that have been nearly destroyed by thirty years of warfare on both sides of the zero line. The United States must also concurrently work with Pakistan to help regenerate the traditional tribal system in the fata as a companion effort to arming militias in Afghanistan.

President Karzai may not be happy with U.S. involvement in a militia program; nor will he view the militias we raise as his natural allies. He will be right. The idea of an Afghan presidency designed somehow to control all of Afghanistan was built into the system when the interim government was established in Bonn in 2001. It was a mistake then, as now. The new administration and the new special envoy should correct this as they cajole into existence a presidency with natural Afghan limits and begin to work out new relationships with the outlying governors who hold real power outside Kabul. Whenever Afghanistan has been “well ruled” in the past, those at the helm in Kabul understood their limitations in dictating to the provinces. That balance will have to be reestablished.

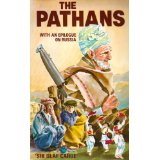

In taking these steps, the United States should not expect any long-term gratitude from the militias it arms. At best we should hope that they might restore an old order as they beat back the nihilist upstarts on either side of the border. The arms flows should be structured to prompt continuing good behavior—a tall order, but not an impossible one. The last British political agent in the fata, Sir Olaf Caroe, was able to keep the tribes “quiet” during his tenure (in the 1930s and 40s) by rewarding “good” behavior with a continued flow of cash and arms. Caroe’s The Pathans should be read by all involved in this challenge, maybe even before picking up the new Petraeus doctrine on counterinsurgency.

As with all of the other problems the new administration faces, Afghanistan and Pakistan need new, even radical, rethinking if the United States is ever to reverse a failing enterprise. The only certainty about Afghanistan is that it will be Obama’s War, as surely as Iraq is Bush’s War and Vietnam was Lyndon Johnson’s War. The president’s new team for Afghanistan and Pakistan has been dealt a losing hand, but if anyone can turn the tables, they just might be able to do it.

Copyright The National Interest, shared by author in the public interest in full text so as to enable Google Translate.