PDF (15 Pages): Dover Steele PSA April 2014

Dover, R & Steele, RD (2014) Intelligence and National Strategy? Rethinking Intelligence: Seven Barriers to Reform, Paper presented the UK Political Studies Association Annual Conference, Manchester (14 Arpil 2014).

ROBERT STEELE: An Open Source Agency would be helpful but I was naive to expect the US IC to want to do the right thing — or any Cabinet Member to actually want decision-support. Had I known in 1994 what I know today, I would have taken this approach in the first place as a second track, demonstrating the value of decision-support across each of the eight tribes, none of whom do holistic analytics and true cost economics decision-support now. With this piece we begin a new 20-year campaign to teach the willing how do the right thing instead of the wrong things more expensively (Ackoff, 2004). I am looking for a single university that will fund my PhD proposal and also launch a campaign to raise $100 million to create a School of Future-Oriented Hybrid Governance and a World Brain Institute.

Full Text Below the Fold

Intelligence and National Strategy?

Rethinking Intelligence: Seven Barriers to Reform

Robert Dover & Robert David Steele1

2013 will come to be seen as a key year in the historical development of intelligence as a government-led practice, and in the understanding and development of the relationship between government and the citizenry on both sides of the Atlantic. Whilst the classic balance between security and privacy has been an oft cited trope within intelligence studies and those who comment upon it, 2013 has provided a catalyzing moment for the political reform of intelligence activity. We have drawn our terms of reference to include both the US and British intelligence communities due to the closely bounded nature of these two sets of institutions and their interlocking activities (Scott, 2012).

This paper begins with the premise that intelligence is an important and integral part of the bureaucratic processes that account for the term ‘government’, and that many of the areas, issues and practices that fall outside of the focus for intelligence studies – such as electoral politics, opinion polling and international political economy – actually have a large impact upon intelligence practice. We also start from the assumption that any study of intelligence should necessarily fall wider than the classic intelligence studies concerns of narrowly defined processes, architecture or historical case-studies of failure. This paper therefore seeks to re-think the term ‘intelligence’, and to contextualize it within wider political and bureaucratic processes, grounding the intelligence community in its core functions and away from the wider roles it has – we believe – erroneously acquired.

On both sides of the Atlantic the foundational contexts for this rethinking of intelligence are comparable. There is a wide-spread public discontent with the established parties within both the US and British electoral systems, and a growing disconnection, therefore, with the government (of any color) as a relevance to the lives of ordinary individuals (Adams, Green, & Milazzo, 2011). All too often the activities of governments are described in terms of them being a hindrance or intrusion into everyday life as opposed to being facilitative, enabling or supportive. In the UK this discontent has developed over a long period and modern historians and chroniclers would suggest a panoply of dates, and a similar spread of issues. A consistent theme of financial inappropriateness that the popular press has described as ‘sleaze’ has tarnished the reputation of Parliament since the mid-1990s, but it has had the effect of distancing the electorate from their representatives (Whiteley, Sanders, Clarke, & Stewart, 2013). In turn, this has had the effect of distancing the electorate from government activity. We cannot point to causation, but strongly suggestive correlations. For instance, the sustained criticisms of the British government’s use of intelligence to justify the 2003 Iraq war strongly impacted on the 2013 decision not to go to war with Syria, despite the vastly superior intelligence and rationale for conducting military operations. So throughout this paper, there is a watermark which questions the popular legitimacy of much intelligence activity. We argue that this is partly due to the relative health of our democratic systems, and partly due to specific pieces of conduct of those communities. If flawed intelligence processes reduce the legitimacy of the government, neither the government nor the public are well-served.

The second foundational element is the state of government finances on both sides of the Atlantic. The historically high deficits a nd corresponding measures to control these deficits have generated considerable commentary as to where the burdens should fall to reduce the level of indebtedness: should these fall on additional taxation, or on cuts (which proportionately impact on the lower socio-economic groupings). Mixed in with this have been widespread commentary about the use of intelligence to support trade and business activity, the use of intelligence to identify, contain and roll-back political dissent (Lubbers, 2012) and the over-reaching of those agencies to do so. We argue that these factors have coalesced to move the intelligence community from being part of ‘us’ to an outsider position as ‘them’.

The third foundational point is then the revelations of Edward Snowden concerning the US National Security Agency and the UK’s equivalent, the Government Communications Headquarters as signals and electronic intelligence facilities, that were shown to have put together systems of surveillance that were vastly misaligned with public understanding of surveillance activities, and appeared to have also run out of alignment with what legislators thought they had enacted into law, and which they thought they had overseen through scrutiny committees. On the US side, these revelations have prompted the President to initiate a review of current intelligence custom and practice, and thus this moment of acute and publicly played out shock provides a permissive backdrop to a scholarly rethinking of intelligence, and indeed the role of government in these activities (Obama, 2014).

This paper introduces and discusses seven core barriers to reform that have allowed the respective intelligence communities to cost the US taxpayer some $75bn per annum and the UK taxpayer circa £17bn per annum, while avoiding accountability for systemic and specific failures. Neither intelligence community on either side of the Atlantic has been effectively held to account for acts that many commentators judge that fit within the internationally recognized parameters of crimes against humanity: from the rendition and torture programs (carried out with impunity) (Grey, 2006), to extra-judicial killings via unmanned aerial vehicles or drones across Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia (Medea & Ehrenreich, 2013), to the deeply intrusive, warrantless and persistent surveillance of citizenry ‘at home’ (Ball & Ackerman, 2013).

1) Secrets are intelligence

One of the most persistent features of the discourse around intelligence is that secrets equate to intelligence. Various grandees and scholars of intelligence have all proffered variations on this theme, be it that government information is intelligence (Kent, 1949), that privileged government information is intelligence (Dover, 2007), that secret government information is intelligence (Herman, 1996) and that secret government information that leads to the tasking of a government asset is intelligence (Ferris, 2005), and that intelligence is an umbrella term for government activity in the secret space (Gill & Phythian, 2012). The collection of information (be it covertly or via open source methods) is a technical exercise. Warehousing data, which is the predominant activity of the intelligence community currently is not, we think, intelligence. A definition of intelligence that both makes it clear what the range of activities is and should be is helpful to the cause of successfully reforming intelligence activity so that it more fully contributes to securing the national interest of both countries. Thus, we advance a definition of intelligence that equates it to ‘decision support’.

Decision-support creates an output, something tangible that has the capacity to be measured. The impact of decision-support on a decision can be both measured in the immediate moment and for its enduring impact over time. Intelligence communities on both sides of the Atlantic maintain a position that everything that carries a classification (the information that has been collected, the means by which it was collected, the purpose for which it was collected) is intelligence, when in actual fact the vast majority of this activity is nothing more than classified information. It is technical in the nature by which information is secured via automated processes, through which the overwhelming majority of it is unprocessed and unanalyzed: it is collected and stored because the technical wherewithal exists to do so. This is a data-centric approach, rather than one guided the core values or interests of the state. By way of evidence for this assertion, General Tony Zinni, USMC has stated (at the time he was the Commander In Chief of the US Central Command or CINCENT), “At the end of its all, classified intelligence provided me, at best, with 4% of my command knowledge.”2 When General Zinni was later asked to explain how he had come to this view, he outlined how he and his immediate advisors had determined that 80% of their useful intelligence was from open source material, collected using open source methods, and within the final 20% that was provided by secret sources and methods, 80% of that final element was of a lesser utility than those provided by open sources, once these were engaged.

When President Harry Truman created the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1947 he was seeking to create a centralized and objective creator of decision-support – an organization that could process and integrate into wider government all the usable information that was being collected across the US government. The misalignment between Truman’s intentions and how the CIA operated ultimately led him to write an open letter in The Washington Post calling for a re-examination of the CIA:

“..every President has available to him all the information gathered by the many intelligence agencies already in existence. The Departments of State, Defense, Commerce, Interior and others are constantly engaged in extensive information gathering and have done excellent work. But their collective information reached the President all too frequently in conflicting conclusions. At times, the intelligence reports tended to be slanted to conform to established positions of a given department. This becomes confusing and what's worse, such intelligence is of little use to a President in reaching the right decisions. Therefore, I decided to set up a special organization charged with the collection of all intelligence reports from every available source, and to have those reports reach me as President without department “treatment” or interpretations. I wanted and needed the information in its “natural raw” state and in as comprehensive a volume as it was practical for me to make full use of it. But the most important thing about this move was to guard against the chance of intelligence being used to influence or to lead the President into unwise decisions — and I thought it was necessary that the President do his own thinking and evaluating… For some time I have been disturbed by the way CIA has been diverted from its original assignment. It has become an operational and at times a policy-making arm of the Government…I never had any thought that when I set up the CIA that it would be injected into peacetime cloak and dagger operations. Some of the complications and embarrassment I think we have experienced are in part attributable to the fact that this quiet intelligence arm of the President has been so removed from its intended role that it is being interpreted as a symbol of sinister and mysterious foreign intrigue” (Truman, 1963)

The majority of the information used by the CIA is open source in nature. It is difficult to evidence this point, save for the public pronouncements of multiple Directors of Central Intelligence (DCI). Much of the operational and normative verve of the CIA that Truman was so concerned about originated in the intellectual reparations sought from vanquished enemies from the second war (Yeadon, 2008). In a move that is resonant with that which occurred after 9/11, the core missions of the US intelligence community, in particular, were bent towards a self-serving budgetary expansionist focus upon the threat from communism from 1947 onwards, and then from Jihadism from 2001 onwards. The consequence of this focus was to distract the intelligence community away from its responsibility and the need to provide decision support, and from a need to adequately respond to complexity in the international system, and in assessing threats (Fuller & Snyder, 2009). Instead it became an action arm, a regime change arm, often mis-guided for lack of the very intelligence it was supposed to be producing. Only now is there an emergent academic literature that seeks to understand formal complexity (the tendency of threats and internation al system to disequilibrium) which strongly suggests that the approach of governments to understanding threats and developments in the international system are premised on factors that are not intrinsically part of the analytical problem (Cairney, 2012). Stephen Marrin describes this phenomenon as ‘information push’ (Marrin, 2009), whilst Loch Johnson quoted President Carter in saying, ‘the intelligence community itself set its own priorities as a supplier of intelligence information’ (Johnson, 1986). And thus in the intelligence community setting the requirements for what they think the policy community should be interested in, or what they wish policy makers to be interested in rather than be agents of decision support, the community is reduced to collecting, analyzing and disseminating product of their choice, whilst making a narrative claim that this is serving the policy community and the interests of the electorate. Such a problem has been long identified in the margins by producers as well as commentators, the careful ‘delineation’ of the intelligence producer from the policymaking process to avoid partiality in the production of intelligence (Forbush, Chase, & Goldberg, 1976). Our contention would be – therefore – that the intelligence community has become a player on the political stage in its own right, a norm entrepreneur, guided by multiple bureaucratic imperatives to seek marginal outcomes to justify budgetary, human and technical resource and in a Keynesian way to maintain the supportive industries around the intelligence community.

2) The collection of secrets for the Core Executive justifies the entire activity

Along with “if you only knew what we know,”, which became a core part of British Prime Minister Blair’s case for the war against Iraq (Phythian & Pfiffner, 2008) “secrets for the Prime Minister or President” (Andrew, 1996) is the line of last resort ultimate get out of jail free card, both here and across the developed world. The US intelligence community has argued in Congressional testimony and published commentaries that the circa $75 billion annual spend is fully justified solely on the basis of information provided to the President (Lowenthal, 2012). Similar claims are made in the UK around the resource allocated to the Single Intelligence Account (the unified intelligence budget for all the principle agencies), but in the UK such justifications are made by the executive level politicians accountable for the activity (e.g.: the Prime Minister, the Home Secretary and the Foreign Secretary), rather than the justification being levelled by the agencies themselves. This is partly a difference in political and organizational culture, but also is intended to be read as positioning the UK agencies as servants of the Crown, whereas it appears to be better accepted that US agencies are actors in their own right. However, the claim that all intelligence activity is justified because of the information supplied to the executive, be it the President in the US, or the Prime Minister, National Security Committee and individual ministers in the UK is partly undermined by the growing list of incidences where the product delivered was later shown to be critically inaccurate, or where agencies were the cipher for foreign influence or where expansion into policy areas was counterproductive – be it in terms of the quality of product that could be achieved from this perspective or the political fallout from the presence of the intelligence community working on those issues.

If we focus on the US intelligence spend in the first instance, the circa $75 billion per annum figure equates to around $205 million per day on a straight line equation. Excluding the capital spend on buildings and computing architecture (for example), the typical consulting rate for Ivy League Professorial faculty is $2000 per day, which in turn equates to 102,500 professorial consultancy days, per day: the sheer quantity of world-class open source information that equivalences across from the government’s intelligence budget is impressive in absolute and relative terms. The core issue for intelligence reform is, therefore, whether the $205 million a day as currently obligated provides value for money when mapped across the need to provide functions such as decision support, providing competitive advantage in the international system, horizon scanning for international challenges and threats, responding to aggression from adversaries (another form of decision support) and understanding competing cultures. So, whilst the information revolution has provided us with an unparalleled access to knowledge drawn from across the globe, this has yet to be appropriately harnessed by the government level intelligence community which has remained wedded to its existing methods and organizational architecture.

There are three principle weaknesses with the established and embedded approach to government intelligence:

Firstly, only an estimated ten percent of the budgets of US and UK intelligence communities is spent on the analytical community.3 Given the importance of analytical work to intelligence and decision support, this is a disproportionately small percentage. There has also been a limited discussion within think-tank and research institutes around the quality of the analytical pool: the average age of the analytical pool has reduced markedly since 2000, often leaving newly graduated officers in positions of considerable influence, whilst experienced officers have either faced redundancy (certainly in the case of Sovietologists, which now would seem an error given the activism of the Russian state and the paucity of analytical expertise on Russia) or have sought careers on better terms outside of government circles. The private security market place is now busy with former intelligence officers and analysts seeking to apply and sell their methods into new challenges.

Secondly, intelligence communities have been resistant to the notion that they can deal openly with outsiders. The rationale for this is based around a risk aversion surrounding possible leakages, or vulnerabilities in getting openly close to unvetted sources of knowledge and expertise. The predominating taxonomy that works within the intelligence community looks at those of utility outside the community as those providing information against the wishes of the object (traitor), a source being listened to or surveilled (a target), or an external contractor (hired help). The focus on this exploitative and exclusionary taxonomy means that the intelligence community is ineffective in its quest to harvest knowledge from external nodes of information in the open source space, including: academic, civil society, commerce especially small business, government especially local, law enforcement, traditional and new media, military, and non-government/non-profit third sector. But as the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council pilot study held by one of this paper’s authors demonstrated, with appropriate controls academic experts can provide open source insights and challenge to a government community.4 The problems – even of commissioning scholars who would not pass clearance for government employment – are not insurmountable, nor are they particularly burdensome.

Thirdly, the principle output the American intelligence community provides the President is the President’s Daily Briefing (PDB), and a collection of (often counterproductive) covert action programs (e.g.rendition, special measures, and unmanned aerial vehicles). Colin Powell, at the time privy to the PDB, says in his memoir My American Journey, that he found the Early Bird published within the Pentagon – the compendium of relevant news from around the world – to be more useful (Powell, 2003). But outside of these examples it has been noted on both sides of the Atlantic that the role of the intelligence analyst has been reduced from providing analysis to focusing on providing a rolling log of events or news. Such a position does not provide decision support at all, at the same time that no other capability is mandated to achieve the desired end of timely, relevant, reliable decision-support.

We would propose that the legislators and the governments of the US and UK should be concerned with four key approaches to the evaluation of intelligence. These four approaches are: 1) evaluating processes; 2) evaluating the purpose; 3) evaluating sources and 4) evaluating the utility. For each of these approaches sits values and specific action points. So, in terms of evaluating process there is a need to evaluate the collection, processing, analysis and delivery of information, whilst holding the values that sit behind the core purpose of intelligence, that of decision support to the fore. Such an overview should also be cognizant of the temporal and spatial issues surrounding information. When evaluating the utility of intelligence, the value set employed should be focused around the timeliness, precision, effect and through-life cost of intelligence, whilst a precise evaluation would include a view of the utility of intelligence when mapped against the view of the target, the view of recipient, from the perspective of maximizing the utility for the public and for the practitioner. An evaluation of the sources should include a relative weighting and utility against information that could be drawn in from all open source avenues, without geographical, linguistic or temporal restriction. When evaluating the purpose of intelligence, there should be an evaluation that starts with the values of clarity, diversity and integrity of purpose and intelligence. Such an evaluation should also consider the extent to which the state seeks to use intelligence machinery to garner various kinds of advantage and forewarning in the international system.

As many commentators have noted, a key flaw in the prevailing system of intelligence is the critical disconnect between the managerialism of meeting key performance indicators generally associated with fully spending one’s assigned budget, versus being committed to the advancing the cause of the nation, serving the needs of a complex, sophisticated and developed government, operating in an international (and indeed domestic) environment that can be characterized as being riven with complexity. So, far from it being the case that only the core executive requires decision support, it can be clearly identified that Cabinet Secretaries (US), Junior Ministers (UK) and further down to bureau and branch chiefs and their individual country or topic desk officers. The reality of Departments of State (UK) and Cabinet Departments (US) do not do “decision-support,” nor do they do strategic planning, programming, and budgeting as would be practiced – for example – by military professionals. Departments of State and Cabinet departments (as well as intelligence agencies) are primarily concerned with “budget share” constancy and the protection of their stakeholder interests: as we would term it job security rather than national security. Neither Congress nor the Houses of Parliament in the UK receive intelligence support across the authorizing, oversight, and appropriations functions, all of which are dependent on the Congressional Research Service (CRS) in the US and the Parliamentary researchers. Both of these organisations do a highly credible job in the context of their resourcing and remit – but neither produces “decision-support” per se, at the same time that both Parliaments are susceptible to alternative information feeds from lobbyists and interest groups, which are not seeking to provide decision support in the national interest.

3) Only government agencies know how to do intelligence

If intelligence is defined as secrets for the executive (be it the Prime Minister and Cabinet, or the President) then the respective communities discharge their responsibilities ably. The US community has been particularly susceptible to a form of military-industrial-complex whereby a secondary (but important) driver has been the need to keep circulating financial through-put, and GCHQ’s involvement in NSA programmes has brought a little of this tendency to the UK. The absence of effective accountability and oversight on both sides of the Atlantic merely serves to exacerbate this tendency where it exists and the pursuit of a pure science inquiry (eg developing technology, techniques and surveillance because it can be done, rather than that it serves a useful national security purpose for it to be done). The absence of adequate political oversight (although it is not clear that political oversight even in an intrusive form is particularly useful), and transparent audit processes has contributed to the current perception of the intelligence services having ‘gone rogue’. We argue that intelligence should be defined as decision-support, and that this support should be factored in at the strategic, operational, tactical, and technical levels. There is considerable evidence of individual analysts and officers attempting to do just this within their respective agencies and from an individual perspective of trying to effect positive change. But systemically the intelligence community should be seeking to do the following:

a. Develop requirements and manage all-source collection and all-source production consonant with a complex analytic model that integrates the predominant threats to humanity (not just narrow national threats), across core policy areas.

b. Produce intellectually deep and broad intelligence essential to defining national security strategy, which then informs the military and security planning processes.

c. Produce timely diverse intelligence (decision-support) essential to force structure acquisition, and in terms of the hyper-competitive threat across sectoral areas including engineering and trade and in terms of designs, materials, industry partners, supply chain vulnerability, and so on. This activity should also include a level of work akin to counterintelligence against those who seek to diminish home interests in this way.

d. Produce timely culturally sensitive and accurate intelligence (decision-support) for complex operations.

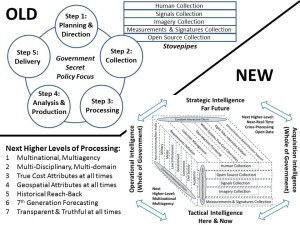

Some of these concerns and indeed critiques of intelligence community activity are not new. Indeed, criticism of ‘old’ ways of working, including a reliance on the intelligence cycle, of institutional silos and stovepipes and on producing synthetic intelligence product that mostly then is archived are as they were when these critiques began to gain traction. The following figure was created by one of this paper’s authors (Steele) to demonstrate an alternative way of conceptualizing the intelligence process, as it should be, rather than as it is.

Figure one: A reconceptualization of intelligence.

4) The value of secret technical collection is overstated

As much as ninety-five percent of the raw intelligence collected by the NSA and GCHQ never gets processed, that is analyzed in a wider context beyond merely storing it for potential future use. One of the startling revelations of the Snowden scandal and its aftermath was that it had been assessed that the population wide surveillance had yet to result in a terrorist plot being spoiled. It would be reasonable to conclude – at that point – that either the program was effective, or that its purpose is not counterterrorism? If we move from signals and electronic intelligence to imagery intelligence it should also be of concern that the western world still does not possess 1:50,000 combat charts (military maps with contour lines and cultural features) for an estimated eighty percent of the world. During the Somalian operations, US forces are still today obliged to use Soviet produced 1:100,000 charts. When Bosnia and Kosovo were a designated combat zone in the 1990s, seven laptops with digital maps were the best the US National Geospatial Agency (NGA) could do – some of these realities are beyond parody and given the consequences of the operations into tragedy also. Whilst some of these observations might fall into the category of being somewhat lurid, they serve to highlight that whilst the capabilities of the intelligence community are constantly referred to in terms of being ubiquitous, they are – in many important respects – less than those that could be found, for example, in universities. The key problem is in how to utilize on the considerable intellectual capital that is possessed by universities, third sector organizations and so on, for this intelligence effort.

So, if one wanted to make a market assessment of the value of the intelligence community’s secret technical collection effort, it might not amount to a significant percentage of the capital outlaid for it. A move towards capitalizing on open source strands would not only improve the technical quality of the intelligence but also the value for money equation that is often at the forefront of policy makers minds. We argue that there are myriad in efficiencies generated by understandable security concerns: the analyst should be a citizen of the world and well-connected and yet simultaneously closely controlled and disconnected. Whilst this tension is never likely to disappear, a reorientation of disposition towards counterintelligence and connectivity could be usefully worked through.

5 & 6) A Challenging Thought: Government and Elected Representatives do not need intelligence

The entire Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System (PPBS) is fact-independent. Whilst there is an industrial effort to solve problems as they occur and to scan horizons for future threats, these are done within a tightly constrained institutional and cultural framings. Without a critical reorientation of these pre-sets, and of the cultural framing to intelligence, then intelligence will remain a secrets generating activity, rather than one which usefully supports decisions and contributes to the national interest.

As regards Congress and Parliament, both have research arms, and both take seek out and receive advice and information from qualified outside sources. But neither have an intelligence function, and the process of receiving evidence or testimony from outsiders is sporadic and often subject to the vagaries of personal connection and contacts. So, in formal governance terms, crucial components of the governance of the respective nations are done without access to rigorous intelligence process or intelligence-led decision-support. The capacity of elected representatives to make consistently sound judgments, or to check and balance the judgments of the respective executives is therefore hindered by the absence of a decision support capacity. Consequently, to paraphrase Chuck Spinney, the situation present now is amateur hour. That is, decisions done in our name and funded by taxpayer money can be often judged to be antithetical to the national interest, because they are not done to an appropriately rigorous standard and are informed by interested single-issue lobby groups rather than by an objective element or a public network.

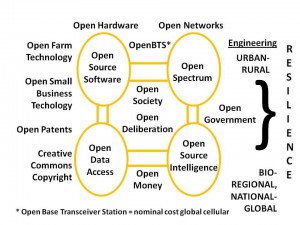

One of our conclusions is that both the American and British intelligence systems would benefit from a variation of an Open Source Agency (see figure below), an executive body that would service the security community and elected officials by providing Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) while also nurturing the various open source technologies so as to achieve a universal and affordable, inter-operable, and scalable ability to share information and make sense across all boundaries. This would allow them to operate from a common foundation of best truths. In December 2004, a UN High Level Panel reported on Threats, Challenges, and Change. (UN, 2004) This group listed poverty as its top global threat, followed by infectious disease and environmental degradation. Terrorism and interstate conflict came as the eight and tenth on the cascading list of priorities, which is – of course – the stock trade of intelligence agencies. The optimal response to this threat assessment is the creation of a global intelligence commons on the principle threats, whilst refining national intelligence capabilities towards complex adaptive systems that supports both the executive and elected officials.

Figure 2. An Open Source Ecology

7) The public does not need intelligence – the government will do it for them

We leave for another time the most important false premise of our present relegation of the craft of intelligence to the uncertain ties (or perhaps false certainties) of current government practices. One can certainly posit a need for decision-support – for the application of the proven practice of intelligence, which is to say, requirements definition, collection management, source discovery and validation, multi-source fusion, machine and human analysis, and compelling actionable presentation of tailored responses to precise questions from specific individuals or small groups – among academics, civil society organizations including labor and religion, commerce including small businesses, government at the local and provincial levels, law enforcement in all its forms, the military and particularly in relation to acquisition, and among non-governmental or non-profit organizations.

The evolving craft of intelligence, in our view, is at the end of the beginning, at the end of its gestation in the iron crib of government (Steele, 2013). The craft of intelligence is a public craft, a craft that is most personal, most political, for it is the epitome of human understanding, the pinnacle of the applied humanities, melding the lessons of history, the morals of culture, and scientific inquiry, to the utility of decision-support.

NOTES:

1 This paper is the product of an ongoing collaboration between Dr Robert Dover (Loughborough University), and Robert David Steele

(http://phibetaiota.net/) a former CIA clandestine service case officer. This is a dialog that is rare today in academia, with this joint academic version of the argument we are beginning what we hope will be a twenty-year advance in the evolving craft of ntelligence. The paper itself represents an ‘intelligent firstpass’, and will be further refined before publication.

2 As cited in Robert Steele “Open Source Intelligence” (Strategic) in Loch Johnson (Ed), Strategic Intelligence: The Intelligence Cycle (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007), Chapter 6 pp. 96-122.

3 There is no single point of reference for this calculation, based on multiple expert opinions including Office of Management and Budget (OMB) opinions. It is generally established that 70% of the total budget is spent on contractors, and that the majority of the budget is spent on technical collection – clandestine human collection is a tiny fraction of the total, and the processing of the technical collection is miniscule – on the order of 5% at best. Within the totality of millions of people and over 2,500 compartmented collection programs, the analysis endeavor comprised of CIA and DIA analysts, analysts at the service intelligence centers, and analysts at the theater or regional commands, could not possibly be greater than 10%.

Bibliography

Adams, J., Green, J., & Milazzo, C. (2011). Has the British Public Depolarized Along With Political Elites? An American Perspective on British Public Opinion. Comparative Political Studies, 507-530.

Andrew, C. (1996). For the President's Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and the American Presidency from Washington to Bush. London: Harper Collins.

Ball, J., & Ackerman, S. (2013, August 2). NSA loophole allows warrantless search for US citizens' emails and phone calls. The Guardian.

Cairney, P. (2012). Complexity Theory in Political Science and Public Policy. Political Studies Review, 346-358.

Dover, R. (2007). For Queen and Company – The Role of Intelligence in the UK’s Arms Trade. Political Studies , 638-708.

Ferris, J. (2005). Intelligence and Strategy: Selected Essays. Abingdon: Routledge.

Forbush, R., Chase, G., & Goldberg, R. (1976). CIA intelligence support for foreign and national security policy making. Studies in Intelligence.

Fuller, R., & Snyder, J. (2009). Ideas and Integrities: A Spontaneous Autobiographical Disclosure. New York: Lars Muller Publishers.

Gill, P., & Phythian, M. (2012). Intelligence in an Insecure World 2nd Edition. London: Polity Press.

Grey, S. (2006 ). Ghost Plane: The Untold Story of the CIA's Secret Rendition Programme. London: Hurst & Company.

Herman, M. (1996). Intelligence Power in Peace and War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, L. (1986). Making the Intelligence Cycle Work. International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 1-23.

Kent, S. (1949). Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy. New York: Princeton University Press.

Lowenthal, M. (2012). Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy 5th Ed. New York: Sage.

Lubbers, E. (2012). Secret Manoeuvres in the Dark: Corporate and Police Spying on Activists. London: Pluto Press.

Marrin, S. (2009). Intelligence Analysis and Decision Making. In P. Gill, S. Marrin, & M. Phythian, Intelligence Theory: Key Questions and Debates (pp. 131-150). Abingdon: Routledge.

Medea, B., & Ehrenreich, B. (2013). Drone Warfare: Killing by Remote Control. London: Verso.

Obama, B. (2014, January 17). Remarks by the President on Review of Signals Intelligence. Retrieved from The Whitehouse: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/01/17/remarks-president-review-signals-intelligence

Phythian, M., & Pfiffner, J. (2008). Intelligence and National Security Policy Making on Iraq: British and American Perspectives. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Powell, C. (2003). My American Journey. New York: Ballantine Books.

Scott, L. (2012). Reflections on the Age of Intelligence. Intelligence and National Security, 617-624.

Steele, R. (2013). The Evolving Craft of Intelligence. In R. Dover, M. Goodman, & C. Hillebrand, Routledge Companion to

Intelligence Studies. Abindgon: Routledge.

Truman, H. (1963, December 22). Limit CIA Role to Intelligence. The Washington Post, p. A11.

UN. (2004). A More Secure World: Our Shared Responsibility. New York: United Nations.

Whiteley, P., Sanders, D., Clarke, H., & Stewart, M. (2013). Why Do Voters Lose Trust in Governments? Public.‘Citizens and Politics in Britain Today: Still a Civic Culture? (pp. 1-38). London: LSE.

Ueadon, G. (2008). The Nazi Hydra in America: Suppressed History of a Century. New York: Progressive Press.