Peacekeeping Intelligence Leadership Digest 1.0[i]

Robert David Steele

Ben de Jong, Wies Platje, and Robert David Steele, PEACEKEEPING INTELLIGENCE: Emerging Concepts for the Future (OSS International Press, 2003), pp. 201-225.

Executive Summary

The Brahimi Report, in combination with documented field experience from numerous UN peacekeeping missions, and the memoirs and published statements of recent secretaries-general, make it clear that the time has come to establish strategic, operational, and tactical intelligence concepts, doctrine, and tables of organisation & equipment (TO&E) for intelligence support to UN decisions at every level. This Peacekeeping Intelligence (PKI) Leadership Digest 1.0 integrates key expert insights, and represents a first step in the long-overdue establishment of UN competency in the craft of intelligence.

Introduction

Possibilities for Failure

Purpose and Structure of the PKI Leadership Digest 1.0

Figure 1: Overview of the PKI Leadership Digest 1.0

Strategic Intelligence

Strategic Collection

Strategic Processing

Strategic Analysis

Strategic Security

Notional Strategic Organisation

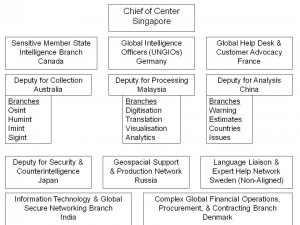

Figure 2: Strategic Intelligence Secretariat, United Nations

Operational Intelligence

Operational Collection

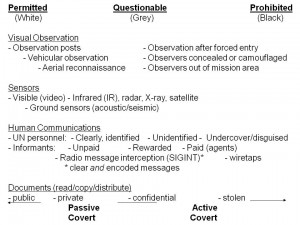

Figure 3. Information-Gathering Spectrum from Permitted to Prohibited

Operational Processing

Operational Analysis

Operational Security

Tactical Intelligence

Tactical Collection

Tactical Processing

Tactical Analysis

Tactical Security

Concluding Observations

Endnotes

Full Text Online for Ease of Automated Translation

Introduction

Peacekeeping Intelligence (PKI) is substantially different from combat intelligence, which the military is accustomed to, or law enforcement intelligence, which some but not all police forces understand. It requires, above all, a different mind-set on the part of the commander and his staff, as well as all personnel, both officer and enlisted. Indeed, it introduces civilian personnel, and non-governmental personnel, into the actual day-to-day collection, processing, and analysis of raw information from multiple sources. It relies very heavily on open sources of information as well as substantially more direct observation and elicitation from varied indigenous sources and largely by non-intelligence personnel, military police and normal infantry patrols, inter alia.

Peacekeeping intelligence is different from national intelligence in one other important way. As Hugh Smith has stated so eloquently:

The concept of ‘UN intelligence’ promises to turn traditional principles of intelligence on their heads. Intelligence will have to be based on information that is collected primarily by overt means, that is, by methods that do not threaten the target state or group and do not compromise the integrity or impartiality of the UN. It will have to be intelligence that is by definition shared among a number of nations and that in most cases will become widely known in the short and medium term. And it will have to be intelligence that is directed towards the purposes of the international community.[ii]

Fortunately, in the 40 years since the first Military Information Branch sought to protect UN peacekeepers at risk in the Congo, there have been dramatic changes in the international information and intelligence environments. The Internet, beginning in the mid-1990’s and exploding into global prominence at the beginning of the 21st Century, has made rapid access to vast volumes of information possible from literally anywhere. The implosion of the Soviet Empire, and the emergence of Russia as an interested party in the stabilisation of the Muslim crescent along Russian Southwest border, has had one extraordinary benefit for UN peacekeepers: the release into the public domain of Russian military combat charts, all with cultural features and contour lines, at the 1:50.000 scale, and for ports and capital cities, at the 1:10.000 level. Coincident with the release of the Russian military maps there has been a great leap forward in commercial imagery, with French 10-metre, Indian 5-metre, Russian 2-metre, and American 1-metre satellite imagery now being easily available and even better, easily directed toward any particular target at any particular time.[iii]

Partly as a result of the dramatic changes in information technology and the availability of what is now called open source information (OSIF), there has occurred a Revolution in Intelligence Affairs (RIA), and an independent discipline, Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) has emerged, both to meet the needs of organisations that are either nor permitted to, or that voluntary eschew resort to, clandestine and covert means of acquiring information, and to enhance the understanding of nations, the Member States of the UN, that have relied on spies and secrecy for so long that they have in many cases lost touch with the real world.[iv] The real world is a world in which tribes rather than armies—criminal gangs rather than political parties—environmental conditions rather than treaties—are the dominant forces that determine whether an areas is stable or unstable, governable or ungovernable. For many national intelligence organisations, the instability of the Third World has been of little concern, and they have no established covert collection assets that can really be brought to bear. Hence, OSINT emerges as a very viable foundation for peacekeeping intelligence.[v]

OSINT is so viable that the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), seeking a solution for the challenge of establishing a common appreciation of threats of common concern to NATO and to the Partnership for Peace (PfP) countries, made a commitment to test and develop OSINT as a standard means of meeting NATO requirements. Many do not realise that NATO is actually similar to the UN in that is does not have its own dedicated intelligence capabilities, but has been forced in the past to rely on whatever intelligence the allied powers might wish to share. OSINT represents independence.

Today, as the UN considers how best to implement the recommendations of the Brahimi Report[vi], there are three distinct courses of action for any UN leader or Force Commander desiring to substantially improve the possibilities of success for existing and future UN missions addressing complex emergencies:

1) Structure. The Brahimi Report is brilliantly on point when it emphasises the urgency of creating a permanent decision-support structure at the strategic level, while also stressing the importance of being able to mobilise the appropriate mix of experts in advance of mandates being defined, for operational peacekeeping missions. With 75.000 UN peacekeepers deployed around the world, there should be established organic intelligence units for every mission at the operational level, and no fewer than 250 intelligence professionals at the strategic level (UN Headquarters).[vii]

2) Training. There is an urgent need to establish a complete intelligence training curriculum at all three levels of peacekeeping: strategic, operational, and tactical. Such a curriculum must be able to teach the proven process of intelligence[viii], along with a deep understanding of the many open as well as national sources that can be drawn upon to prepare for and guide peacekeeping operations under varying conditions of risk.[ix]

3) Open Sources. As NATO has done so well at defining OSINT possibilities for coalition operations[x] we will not emphasise the utility nor the details of OSINT, but rather the cost. The heart of OSINT is that it connects the proven process of intelligence with the purchase of legally and ethically available open sources, among which the most important are Russian military combat charts with contour lines at the 1:50.000 level, commercial imagery, tribal orders of battle and anthropological studies, business intelligence on incoming small arms, mercenary hires, and so on. If the UN is to devise a global architecture for proper but legal and ethical intelligence support to strategic decisions about United Nations policies, negotiations and accommodations with Member States, engagements with varied complex emergencies, and subsequent support to missions at the operational and tactical level, then the UN must, quite simply, recognise that there is no element of its budget more important than that which is set aside for the procurement of legal, ethical, open sources of information.

In combination—open sources, training in the proven process of intelligence, and dedicated structure loyal to the UN leadership and responsive to the needs of the UN—these three new capabilities will not only resolve the existing intelligence deficiencies that have been allowed to accumulate, but they will substantially enhance the ability of UN leaders to be effective in their relations with Member States, their crafting of mission mandates, and their oversight of ongoing peacekeeping missions.[xi] Once fully implemented, a UN intelligence structure may possibly enable preventive diplomacy, long a cherished objective of this most important universal organisation.[xii]

Possibilities for Failure

PKI will often fail at the strategic level, either by a failure to perceive deteriorating conditions that will require intervention, such as was the case with the Belgian failure to prepare for the transition in the Congo[xiii], or, if an intervention is known to be needed, well before the Commander reaches the scene, from a failure of the United Nations and the Member States to arrive at a correct estimate of the situation, in turn resulting in an inadequate or erroneous mandate. A more subtle failure is one of over-extension or irrelevance unrecognised. As one contributor noted, the three main UN missions in the Middle East are routinely ratified each year, with little debate (nor strategic evaluation) of their utility. When such forces disintegrate or deteriorate to the point that they are concerned only with guarding their own security, the UN mission has failed.[xiv]

PKI may fail next at the operational level, where a lack of understanding of the differences between normal military intelligence and PKI will result in poor decisions about what to load and what to ‘leave on the pier’. Digital cameras not normally included in Tables of Equipment (ToE), ‘mall radios’ and cellular telephones in quantity, unclassified computers that can be used to establish a wide-area network (WAN) that includes the varied local authorities and many non-governmental organisations, are but a few examples of what could be and should be introduced into PKI planning by the Commander before departing home base. The other major failure that will occur at the operational level is one of historical or contextual misunderstanding of the belligerents, the issues, or the key personalities.

PKI will often fail at the tactical level, because neither military nor law enforcement nor national intelligence forces as normally trained, equipped, and organised, are sufficient or appropriate for dealing with what William Shawcross calls ‘a world of endless conflict’, where humanitarian assistance—meant to stabilise a society—actually creates and perpetuates black markets that empower warlords and criminals.[xv] PKI requires an ability to establish orders of battle (OOB) for non-state actors; an ability to cast a much wider human intelligence network with much greater indigenous language capabilities than is the norm; and an ability to share sensitive information with a wide variety of coalition and non-governmental counter-parts who are ineligible for any sort of ‘clearance’ in the traditional sense of the word.

PKI will frequently fail at the technical level, in part because traditional military equipment, including intelligence collection equipment, is not suited for operation in urban areas; for distribution down to the squad level; or for focusing on targets that do not ‘emit,’ do not wear uniforms or even carry visible arms, and do not ride in conventional military vehicles with clear markings and known characteristics. Conventional militaries are not trained, equipped, nor organised for being effective in ‘small wars’.[xvi]

PKI is, in short, a vastly more challenging endeavour than most military, law enforcement, or national intelligence professional could possibly imagine.

Purpose and Structure of the PKI Leadership Digest 1.0

The purpose of this ‘PKI Leadership Digest 1.0’ is to provide an orientation for any UN leader, either civilian or military, by distilling the book into 35 pages (47 with notes). The Digest’s organisation is shown below.[xvii]

| Collection | Processing | Analysis | Security | |

| Strategic | ||||

| Operational | ||||

| Tactical |

Figure 1: Overview of the PKI Leadership Digest 1.0

Strategic Intelligence

At the strategic level, there are three co-equal objectives: first, to discern early warning of potentially catastrophic conflicts, both internal and regional, such as would warrant preventive peacekeeping[xviii]; second, to inform the leadership of the UN on a day-to-day basis and during special encounters such as have been common with respect to the efficacy of the sanctions on Iraq; and third, to prepare the SRSG and the Force Commander and their staffs for deployment on a peacekeeping mission.[xix] The preparation is in turn divided into two parts: the exclusively strategic part requires that the Security Council devise and approve a mandate for the mission. The appropriateness of this mandate, the soundness of the strategic appreciation that underlies this mandate, will determine, before a single Blue Beret is deployed, the possibilities of mission success or failure.[xx] The second part, what one might call the strategic-operational transition, brings together and devises intelligence in support of two groups: the operational command element, which must begin to define its concept of operations and requisite force structure, logistics, and recommended rules of engagement[xxi]; and the Security Council and supporting Departmental elements (e.g. for peacekeeping or humanitarian affairs), who must ultimately approve the operational plan by confirming the specific forces and rules of engagement proposed by the Force Commander and concurred in by the SRSG.

It is at this time and this level that the SRSG and Force Commander should make a strong personal commitment to championing the inclusion of organic intelligence capabilities within all assigned forces.[xxii]

At the same time, at this strategic level, the SRSG and the Force Commander should be obtaining the preliminary mandate and operational funded needed to acquire the basic geospatial information needed to both plan the strategic aspects of the deployment, and to support the operational and tactical needs of the mission once in-country. Generally this means the acquisition of at least one full set of the 1:50.000 Russian military combat charts with contour lines for the entire operational area as well as the 1:10.000 Russian charts for ports and capital cities. These are generally also available in digital form for direct integration into aviation and artillery mission support software systems. Ideally the SRSG and Force Commander should also open negotiations with both SPOT Image (FR) and Space Imaging (US) regarding the availability of lower cost archival imagery (generally less than three years old) as well as directed imagery. The US National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) can be of assistance in this regard.[xxiii] Attention should be given at this stage not only to fulfilling the immediate strategic planning needs, but to ensuring that the Force Commander will have continuing access to commercial imagery and such other geospatial services (e.g. commercial imagery post-processing and target analysis to be done by the provider, with the finished products then digitally transmitted to the operational intelligence staff).[xxiv]

The UN peacekeeping mission is much more likely to succeed if strategic intelligence is available in quality and quantity, and if the forces and rules of engagement are proposed upwards rather than downwards. It merits emphasis that one reason the UN must have its own strategic intelligence structure is because the larger troop contributing nations generally have not had intelligence assets focused on the ‘lower tier’ countries where complex emergencies develop, while the smaller troop contributing nations tend not to be able to afford structured intelligence collection, even in areas of immediate interest.[xxv]

In the course of devising the strategic mandate, both the Security Council and the SRSG/Force Commander must consider the reality that the military peacekeeping endeavour is only the security umbrella for a much more complex mix of civilian actors.[xxvi] Therefore, both parties should ensure that the mandate clearly addresses the desired chain of command and relationships among the various UN parties, and that a strategy is devised that provides for intelligence support to all UN elements and for integrated operational planning across civil-military lines once the mission is underway.

As the Brahimi Report points out, policy-makers tend to assume best-case conditions when dealing with worst-case behaviour, and this is most dangerous. Both in Ireland and in Bosnia, for example, best-case conditions were assumed, there was no significant intelligence investment authorised, and as a result, the force commanders were severely disadvantaged and opportunities for containing or improving the situation were over-looked, for lack of proper strategic and operational intelligence resources.[xxvii] Speaking of Bosnia, General Sir Roderick Cordy-Simpson has stated quite clearly, ‘…we did not understand the conflict when we deployed’.[xxviii]

In addition to providing for proper operational conditions, the UN headquarters must plan for a prolonged strategic intelligence endeavour, both in relation to negotiations at the strategic level, including sustained monitoring of embargoes and sanction enforcement by the various Member States, and in relation to strategic-level calculations intended to stabilise ‘highly factionalised situations’.[xxix]

There are several forms such a strategic intelligence activity might take. Among the competing models are those of a ‘think tank’, a ‘joint intelligence centre’ that actually processes and analyses information directly, and a ‘joint intelligence committee’ along the lines of the British model, with the authority to task the various Member States, and to pass judgement on the varied products received in response to its taskings, but without a large specialist staff of its own.[xxx]

A combination of a modest strategic ‘co-ordination’ activity at UN headquarters, with standing regional intelligence centres staffed by the Member States in those regions, with a UN liaison presence, offers another alternative for nurturing a non-intrusive but affordable global intelligence network that relies predominantly on open sources of information and shared multi-cultural analysis.[xxxi]

In the long term, the strategic intelligence competency of the UN is going to depend on whether or not the total culture, and especially the culture of the New York bureaucracy, can be modified to fully integrate intelligence qua tailored knowledge discovery, discrimination, distillation, and decision-support into the ‘art’ of UN diplomacy, negotiation, and operations.[xxxii] More than one observer, but General Cammaert especially, has emphasised the urgent need for the establishment of specialised UN intelligence training centres and specific intelligence courses in support of each of the core UN missions and their key personnel.[xxxiii] Such training is not only required for operational forces, but for the bureaucrats in the various UN headquarters and agencies. It will take fully twenty years to grow a new culture at the UN, one that is both committed to individual competence, and respectful of intelligence as a legal ethical foundation for information decision-making. A regular training program for entry-level, mid-career, and senior executives is vital if this transition from one culture to another is to succeed.[xxxiv]

It merits comment that the lower levels of UN intelligence competency will not be as effective if they are not appreciated at the strategic level. As General Cammaert notes, had the UN in New York understood that the intelligence on the planned genocide in Rwanda was reliable, the outcome may have been considerably more positive.[xxxv]

Finally, at all levels, intelligence may be considered a form of ‘remedial education’ for policy-makers, commanders, staffs, and belligerents.[xxxvi] The proven process of intelligence, drawing primarily on expert open sources both within and external to the mission Area of Responsibility (AOR), can craft ‘learning modules’ for use within negotiations and between parties. At a higher level, overt intelligence analysis can be channelled through the Department of Public Information and to the public, ensuring that UN concerns and perceptions, based on very sound, objective, and non-partisan intelligence, constitute the foundation for the international dialog about the complex emergency being addressed on behalf of all Member States.

Strategic Collection

As a general rule, all of the raw information needed to make sound strategic decisions can be found through open sources. Open sources have been found by the most sophisticated Member States to provide at much as 80% of the inputs to ‘all-source’ intelligence on genocide, terrorism, and proliferation, three topics not normally assumed to be ‘open’. The key for the UN is to combine a planned and adroitly managed mix of purchased commercial services including academic studies, legal traveller observations, and commercial imagery, with a deliberate collection plan that identifies specific information needs and then mandates appropriate legal and ethical collection efforts to satisfy those needs.

It is important to avoid confusing planned direct collection that is legal, with covert collection that is intrusive. The activities of private military contractors (PMC) are a case in point. Deliberate overt collection efforts can be devised, both in the home country of the PMC and in the country receiving their training, to carefully calibrate the degree and nature of the support being provided. The point is that such information does not get delivered to the UN by Member States who are sponsoring the covert support, nor does it appear in the newspaper. A professional intelligence organisation within the UN must structure and manage the process of collection.

At this level, with an independent collection capability that relies exclusively on open sources of information[xxxvii] the UN will find itself liberated from both dependence on such intelligence as the Member States might choose to provide, and from the indecision that attends those who lack sufficient information to make a decision with confidence that they have at least a reasonable appreciation of the complex matter at hand. It is especially important in the early years that UN strategic collection emphasise both commercial imagery and local photography (both air-breather and hand-held). A picture really is worth 10.000 words, and proper pictures will go a long way toward overcoming the inherent attitude in the New York offices of the UN that all intelligence is inherently manipulative and often wrong.[xxxviii]

By the same token, little appears to have been done to turn the vast global presence of the UN into a coherent decision-support network. More than one observer has noted the extraordinary reach and inherent expertise of the many UN agencies, most of which seem to feel that they are autonomous entities that do not need to respond to direction or inquires from New York. A common training course on intelligence, and a global electronic database of UN employees and their subject matter as well as their cultural and foreign area knowledge could over time become a very powerful tool for legal direct collection.[xxxix]

‘A force commander needs planning information on roads, terrain negotiability, infrastructure, hazards such as minefields and of course tactical positions and strengths of belligerents.'[xl] If the strategic element does not put this together before the mandate is devised, the Force Commander will be at a severe disadvantage from day 1.

At the strategic or UN headquarters level, the military information structure should be planned for worst-case scenarios, and include human intelligence and counterintelligence specialists, foreign area specialists, access to satellite imagery and national databases, and all necessary funds and equipment for both obtaining and exploiting (processing and analysing) geospatial information from many sources.[xli]

Language skills for the mission area are a special concern. Although some nations such as Norway and Sweden have made a strategic commitment to maintain personnel fluent in key languages (for instance, Swahili, which made a real difference in the Congo operation)[xlii], most nations do not take foreign languages as seriously as they should. It would be worthwhile, at this point in the process, to have a single staff officer designated as the Language Liaison Officer (LLO), with the specific responsibility of immediately identifying four groups of language-qualified professionals:

1) Intelligence specialists

2) Non-intelligence specialists

3) Private sector parties available for in-country posting

4) Individuals in any capacity who could be contracted to provide either voice or document translation services via remote means (i.e. ‘on call’).

An on-going aspect of strategic intelligence, one requiring every bit of diplomatic skill and persistence, is that of constantly negotiating and monitoring and nurturing inter-agency information exchanges within individual Member States, and among Member States.[xliii] In essence, as the sole party with over-arching responsibility for a particular peacekeeping mission, it falls to the UN in New York, and its liaison officers to the capital cities of individual troop contributing and adjacent Member States, to play the role of ‘nanny’ in gently but persistently ascertaining if there is information to be shared, and then facilitating the sharing both at the strategic level, and downwards to the Force Commander. If the UN chooses to establish a ‘world-class’ strategic intelligence cadre, these individuals will bring with them a form of global access and global credibility with the various individual national intelligence agencies that may in many instances overcome obstacles to intelligence sharing that emanate from the policy level with its domestic political calculations rather than the needs of the UN, always foremost.

Finally, in the area of strategic collection, the UN can, quite literally, break new ground by pursuing the vision of ‘seven standards for seven tribes’. This vision—a logical descendant of the original concept of noosphere by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and then of the ‘world brain’ by H. G. Wells—puts forward the notion that in the age of information, globalisation, and increased inter-dependence, there are actually seven intelligence tribes, not only the one national intelligence tribe generally recognised by every government. The other six intelligence tribes are those associated with the military, law enforcement, business, academia, NGO’s and media, and religions or clans as well as citizens. By establishing an Internet-based means for harnessing the distributed intelligence of the seven tribes, the UN can become, in effect, the ‘hub’ for the global brain, and can devise new means of rapidly identifying, contracting for, and leveraging relevant knowledge on a ‘just enough, just in time basis’. The seven standards, addressing global open source collection, multi-media processing, analytic toolkits, analytic tradecraft, defensive security and counterintelligence, personnel training and certification, and leadership (with culture development implicit in leadership) are consistent with the new push by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) to use standards as a means of facilitating the global information society.[xliv]

Strategic Processing

A major advantage of open sources is that they can be shared with every nationality as well as with non-governmental participants in the planning process for addressing complex emergencies. One positive function that a UN intelligence secretariat could offer is that of a ‘service of common concern’ for digitising, translating, and making available online all available information, including geospatial information, that is relevant to the planned mission.

With the advent of the Internet, standards associated with web-based information entry and access become important. Coding information with Extended Mark-Up Language (XML), and agreeing on standard ways of adding meta-tags for countries, topics, dates, and locations (XML Geo) will considerably facilitate the exploitation of all available information by various parties.

‘…the UN has little competency in analysis, scenario building, and prediction. Desk officers do virtually none of this, being overloaded with simple information gathering and a minimal of organising’.[xlv] If the UN were to consider some innovative processing solutions, perhaps consulting with George Soros, Ted Turner, and, right in New York, David Cohen, the former CIA manager who is now the Deputy Commissioner for Intelligence for the New York Police Department, as well as Goldman Sachs and other major organisations that have taken processing to its highest level, some gains could be achieved in this area, and open sources could be weighted, clustered, sorted, and visualised automatically, freeing up staff to do more human analysis.

Strategic Analysis[xlvi]

It is vital that the analysis prepared on behalf of the Secretary-General be truly independent analysis reflecting the strategic needs of the UN as a whole, rather than the desires of a specific department or a specific Member State whose analyst on secondment has been directed to come to a specific conclusion. As General Frank van Kappen notes, in his experience, the number of reported refugees and the severity of their reported condition often had less to do with reality and more to do with the specific policy being pursued by individual Member States providing the information to the UN.[xlvii]

Although the UN is a universal organisation with global responsibilities, no one appears to expect it to fulfil a strategic intelligence mission of ‘Global Coverage’. Instead, the expectation appears to be that the UN will embrace the concept of intelligence at all levels, will establish a structure for strategic intelligence as the Brahimi Report suggests, and then, on a case by case basis, surge up it capabilities, perhaps by temporarily hiring specialists who have exactly the right foreign area and subject-matter knowledge for a specific contingency.[xlviii]

By the same token, UN analysis may be rejected by Member States. General Cammaert has cited the refusal of the USSR to speak to Dag Hammarskjold regarding the Congo; the efforts of the US to discredit U Thant on Vietnam; the problems Boutros-Ghali encountered in Bosnia and Rwanda.[xlix] While no Member State desires to deal with a UN that assumes supra-national authorities, there is some considerable value in UN analysis, based exclusively on open sources of information, that can be shared with the public and achieve a credibility with the public across the international community. For the UN, insightful analysis that is trusted by the public could become the equivalent of ‘the Pope’s divisions’.[l]

One means of being effective at the strategic level is to make innovative use of modelling and simulation. Emerging analytic techniques and tools that are ‘off the shelf’ and therefore not costly, could provide UN intelligence with an advantage in its dealings with national intelligence bureaucracies that have been resistant to change away from the old industrial and Weberian model of information processing along factory lines.[li]

Strategic Security[lii]

Although the UN is proscribed from engaging in clandestine and covert actions, it has a need to track any such actions that come to its attention, and in some cases to object and ask a Member State to cease such actions. At the same time, as the UN has long known, but discovered with renewed force in March 2003, it is itself the target of covert operations by a Member State, and has over the course of several months been deceived both tactically and strategically by ostensibly validated secret source material. A security function is needed, not just in terms of protecting the integrity of the UN decision-process, but in terms of critically evaluating all that is put before the UN from the Member States.

At the same time, the UN has a responsibility to protect the confidences of its sources, both those ‘in confidence’ from the private sector and those that are officially secret from Member States—while also protecting the integrity of its deliberations. This means that the UN must, as an immediate and global priority, establish commonly respected and accepted means for moving sensitive information securely among its various elements.[liii] The importance of establishing a reliable trusted means for communicating and protecting sensitive information cannot be under-stated, if the UN is to become a ‘smart’ organisation possessing increased capabilities for receiving, delivering, and exchanging sensitive intelligence.[liv]

Some authorities question the possibility of the UN ever establishing a reliable ‘security clearance’ process, simply because of the constant change in seconded personnel and the wide variety in nationalities passing through various positions.[lv] In the case of UN intelligence, it may be that some combination of permanent military cadre and permanent civilian cadre who are investigated or ‘vetted’ can be used to manage the minority of the information that is sensitive.[lvi] It is important to stress that while security is important, easily 80% to 90% of the information that the UN must process in order to make sound strategic decisions is unclassified and intended to be publicly shared and discussed.

Whilst the UN demonstrates it ‘can keep a secret’, it needs to work with the Member States to devise new means of communicating vital warning and threat information from sensitive sources down to the Force Commander and the contingent commanders, without excessive security constraints.[lvii] Stripping a warning of any reference to its national source, or even the discipline that provided it (signals, imagery, human) could in some cases permit a warning to be delivered that would otherwise be blocked by national security regulations. A professional UN intelligence cadre at the strategic level could over time devise new protocols to enhance UN peacekeeping force protection without placing sensitive sources at risk.

According to A. Walter Dorn, over the course of time, the UN will also have to develop some forms of secret intelligence. He says:

Secret intelligence is even more important in multidimensional PKO’s with their embedded responsibilities: election monitoring, where individual votes must be kept secret, arms control verification, including possible surprise inspections at secret locations, law enforcement agency supervision (to ‘watch the watchmen’), mediation where confidential bargaining positions that are confidentially shared by one party with the UN should not be revealed to the other, sanctions and border monitoring, where clandestine activities (e.g. arms shipments) must be uncovered or intercepted without allowing smugglers to take evasive action.[lviii]

In very high risk areas characterised by clandestine arms shipments, secret plans for aggression or genocide, and threats to assassinate indigenous leaders or to assault UN forces, some forms of secret intelligence are inevitably going to be required and the UN must become reliably competent in this area.[lix]

At the strategic level, the UN must ensure that any intelligence structure it creates is kept free of Member State espionage. Among the reasons cited for US objections to the earlier creation of a strategic intelligence unit were fears that it would become a surrogate for Soviet espionage. Although managed at the time by an African (James Jonah from Sierra Leone) and drawing its information exclusively from open sources, this was never-the-less how the unit was perceived by some US Senators.[lx] It is incumbent on the UN to devise a solution, perhaps involving a Canadian cadre and very strong counterintelligence co-operation with the US, that will protect its strategic intelligence element from both subversion and suspicion.

A subtle aspect of security is that of public perception. Renaud Theunens points out that the international media is actually a competitor of any UN intelligence endeavour, and both are competing to establish a strategic viewpoint on how the peacekeeping operation is actually going.[lxi] The case could be made that on the one hand, the UN must balance the strictest security and counterintelligence measures to protect sensitive information, but on the other hand it must strive to release to the public the very best open source intelligence analysis that it is capable of generating. Whether the story is positive or negative, it is the UN, at the strategic level, that should be defining the story with its superior intelligence. UN document control and UN declassification both leave much to be desired, and require some sustained professional attention in the very near future.[lxii]

Notional Strategic Organisation

The figure below depicts a notional 250-person strategic intelligence organisation that is predominantly devoted to the collection, processing, and analysis of open sources of information, including geospatial information. This same structure could be applied to a multi-cultural regional organisation.[lxiii]

Figure 2: Strategic Intelligence Secretariat, United Nations

Operational Intelligence[lxiv]

Both UN doctrine on ‘military information’ and UK doctrine on intelligence are outdated and inappropriate.[lxv] Peacekeeping intelligence is an emerging doctrine that is distinct from both of these. Richard Aldrich suggests that low- intensity intelligence doctrine can be generic but does not yet exist. It should stress geographical knowledge and broadly distributed linguistic skills, prior historical knowledge, comprehensive understanding of individual personalities, and extensive liaison to all parties.[lxvi]

The initial absence of an intelligence structure placed the Force in a dangerously handicapped position which threatened the lives of UN personnel, the success of ONUC operations, and the reputation of the UN itself.[lxvii]

In peacekeeping operations, the normal battalion intelligence staff of 5-6 people simply will not do. In both Ireland and Bosnia, the numbers went up to 30-40 people per battalion.[lxviii] Force Commanders should plan accordingly.[lxix]

Apart from ensuring that the mission receives the right mandate, the right rules of engagement, and the right force structure, it is possible that there will be no other more important function for the Force Commander than to ensure the establishment of a Force Intelligence Plan that simultaneously creates the operational-level intelligence staff able to manage force-wide collection, processing, and analysis, and also provides for the coherent management of tactical intelligence collection, processing, and analysis.

Situational awareness’ is of paramount importance for the commander, and must include non-military as well as military factors, and must also include the monitoring and understanding of factors external to the immediate mission area. A commander responsible for transitioning an environment toward mission conclusion must maintain an intelligence interest in refugees and displaced persons; politics; economic development; social, cultural, and religious development; and last but not least, crime and corruption. [lxx]

Peace support operations (PSO) differ considerably from traditional military combat operations. Different mandates, rules of engagement, belligerent ‘rules of the game’, almost everything is ‘different’ and this requires that the operational intelligence unit re-orient itself and adjust accordingly. ‘The complex operational environment is unpredictable and asymmetric’.[lxxi] One expert suggests that peace support operations not only must pay greater heed to intelligence, but also could in fact be considered ‘intelligence-driven operations’.[lxxii]

The selection of specific national contingents and specific national support packages may play a role in the effectiveness of the tactical collection effort. As Dame Neville-Jones observes, in Bosnia ‘The zones designated to the different national battalions often became virtually isolated fiefdoms where the forces did their own thing, which, all too often, was not very much’.[lxxiii] If not through pre-selection, then through post-deployment liaison and secondments used for cross-fertilisation purposes, the Force Commander must ensure that the various tactical units are melded into an operational force and not allowed to conduct either intelligence or operations in isolation.

It is essential, because of the maximum vulnerability faced by the force in its very early days, that the Military Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield (MIPB) system be in place from day 1. This system must be understood and implemented down to the platoon level and by ‘all hands’ acting as the eyes and ears of the commander.[lxxiv]

‘Communications without intelligence is noise, and intelligence without communications is irrelevant’. So said General Alfred M. Gray, Commandant of the Marine Corps, in explaining to Congress why the Marine Corps was the only service that fully integrated the management of communications with the management of intelligence. Modern militaries tend to assume unlimited bandwidth. This is simply not realistic for UN peacekeeping operations in remote areas, and it is incumbent on the Force Commander to ensure that sufficient tactically-relevant communications capabilities are introduced into the AOR. In particular, the Force Commander may wish to take lessons from the UNSCOM endeavour and make greater use of concealed networks of video cameras, ground sensors, and remote processing of intercepted signals. In brief, not only must the Force Commander plan for the most robust all-source intelligence network possible, but the Force Commander must also ensure that the redundant and secure communications capabilities are there as well.[lxxv]

A Force Commander can make a difference in intelligence by avoiding any assumptions as to competency levels[lxxvi], and providing early on for a common base of training and clear understandings as to force-wide intelligence objectives. Asking for a mobile training team fluent in both French and English and able to tour each of the tactical units, stand watch with each unit for a week, and ‘set the tone’ for the tactical-operational intelligence interface, may well be one of the Force Commander’s most important contributions to the eventual success of the mission.[lxxvii]

The Force Commander can also make a difference by recognising that both the indigenous parties and the various components of the UN humanitarian system, as well as their relief association counterparts, will all have a generally negative view of ‘intelligence’.[lxxviii] Educating the leadership of all of the parties that the force is in contact with, and stressing constantly the importance of legal, ethical ‘situational awareness’, is an inherent responsibility of the commander. At the same time, for the next several generations, Force Commanders will be responsible for devising, testing, and documenting emerging doctrine dealing with how aggressive the UN should be in seeking out information under different circumstances; with the degree to which overtly collected information could or should be shared with parties to the conflict; with the degree to which covertly collected information should be used in direct demarches to the offending party, and so on.[lxxix]

Another delicate aspect of the operational intelligence situation is that dealing with lawlessness, crime, and corruption. In most cases, neither the mandate nor the force structure will permit the commander to engage in ‘law enforcement’ activities, but information and intelligence relevant to these threats to stability will be encountered. The Force Commander must devise, as Lord Ashdown and General Van Diepenbrugge devised, means of exchanging information helpful to one another’s distinct mandates.[lxxx] In some instances, the intelligence may be so compelling as to suggest special communications to UN headquarters and a recommendation for a strategic decision to change both the mandate and the force structure, augmenting it with a law enforcement mission and law enforcement specialists.[lxxxi]

The matter of crime is not one that can be under-stated. In both Ireland and Bosnia, to take two examples, extortion, bank robbing, and petrol smuggling on the one hand; and prostitution and narcotics on the other, were major aspects of the conflict. ‘Ireland, and subsequently Yugoslavia, re-affirmed the intense and (generally unappreciated) unseen linkage between the growing importance of ‘global issues’ such as organised crime, drugs and illegal trafficking in light weapons on the one hand, and local or regional conflicts on the other’.[lxxxii]

According to one expert observer, in both Ireland and Bosnia there were three ways in which operational intelligence supported the larger information operations objectives: first, by winning public confidence; second by countering misinformation spread by the paramilitaries; and third, by devising misinformation meant to unbalance the paramilitaries.[lxxxiii]

Finally, one observer notes that peace operations, unlike normal combat operations, can actually see the international media emerge as policy drivers and therefore an operational factor to be monitored carefully.[lxxxiv]

Operational Collection

While there will be challenges to the authority of the Force Commander from the national contingents, a basic condition for maintaining good order in the overall collection plan is to require that all tactical collection activities be co-ordinated with the operational headquarters. This is especially intended to apply to French, British, and American special forces.[lxxxv] At all costs the Force Commander must guide the tactical units in ensuring that the ground is ‘not trampled’ and that the modest opportunities for human collection are not corrupted by multiple approaches from different collectors.[lxxxvi]

In conditions of instability where sub-state actors largely unknown to the Western powers are engaged in deadly conflicts with one another, their locations and capabilities may be known, but their plans and intentions require rigorous attentive collection efforts. For this, there is no substitute for human intelligence.[lxxxvii]

A primary objective of the operational collection plan is force protection.[lxxxviii] In this regard, ‘The security or insecurity of transport and supplies is also crucial’.[lxxxix]

Wireless interception capabilities are fundamental, and include both the monitoring of local language radio broadcasts as well as the interception and, if necessary, decryption of communications by all parties. Such capabilities are discreet and ‘invisible’.[xc] It merits comment that the Force Commander must specifically address, in advance of deployment, the inclusion of both intercept operators with local language skills at high levels of competency, and of at least one or two trained cryptographic analysts.[xci]

Aerial reconnaissance capabilities are valuable if they have the photo-interpretation personnel (even one person) and equipment needed to exploit their collection.[xcii] Fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters carrying cameras with large aperture lenses and high magnification (as well as television cameras), and unmanned drones, are all helpful.[xciii] The Force Commander should not overlook the simple debriefing of all aviation personnel, this is best done as a mandatory and regular procedure, to which at least one dedicated team of debriefers should be assigned.[xciv]

The Swedish government’s provision of two Saab 29C aircraft equipped for photo-reconnaissance, and a photo-interpretation detachment, was a major contribution to the security of the force in the Congo. Less readily available were radar sets with which to monitor aircraft activity throughout the operational area, something that every Force Commander should ask for.[xcv]

Critical collection factors at the operational level include population (not just demography but history, culture, religious sites, homes of local leaders); military geography; personalities and detailed background (i.e. military services) of gang leaders; and potential courses of action for each gang, faction, and party, including third parties (private relief agencies, private military contractors).[xcvi]

Targets for operational as well as tactical collection include ‘paramilitaries, volunteers, self-declared police forces, freedom fighters, or even criminal networks and the gangs they control’.[xcvii]

Force Commanders should plan for structured intelligence capabilities able to handle as many as 10-20 debriefings a month, in some instances many more. This is a labour-intensive requirement that should not be assigned to intelligence staff as a matter of conflicting routine.[xcviii]

The availability of indigenous language skills is a major factor in whether or not the operational collection plan can be carried out. While some have relied on locally hired interpreters, they represent severe disadvantages in that they are vulnerable to blackmail and often cannot move freely into territories controlled by other ethnic groups.[xcix]

External open sources are relevant at the operational level. Apart from the Internet, there are subscription-based services including regional news services,[c] as well as foreign area expertise, maps, imagery, and directed legal traveller reconnaissance and business intelligence services.

Recent findings place as a top priority… It is not covert cloak-and-dagger spy work but a carefully planned and executed collection that is sensitive in nature. It requires trained teams working in-theatre for extensive periods of time.[ci]

Under conditions of high risk and when facing situations where a mission may change quickly and demand peace enforcement, it is essential that the Force Commander have the mandate and the funding to support confidential-level human information collection (informants).[cii] The emphasis on human collection shortfalls, and the urgency of correcting those shortfalls to provide proper intelligence support to the Force Commander, is a constant theme in virtually every professional review of lessons learned from prior peacekeeping operations.[ciii]

Effective peacekeeping requires the proactive acquisition and prudent analysis of information about conditions within the mission area. This is especially true if the operation is conducted in a hazardous and unpredictable environment and the lives of peacekeepers are threatened[civ]

By the same token, under conditions of high risk and in the face of overwhelming challenges to the adequacy of any UN-controlled operational intelligence endeavour, it appears generally accepted, at least at the highest levels of those engaged in Bosnia, that the American contribution in terms of signals interception from national and field capabilities, are essential. According to General Sir Roderick Cordy-Simpson, ‘…we would have been in dead trouble in any operation without them…I would emphasise time and time again that the intelligence which the Americans brought with all their capabilities was something that I know that I as a commander on the ground I simply would not have survived without’.[cv]

A countervailing point of view is that the Americans are too dependent on technical intelligence sources. The commanding general of Saudi forces during Desert Storm, for example, has stated: ‘I was struck by the fact that in their intelligence gathering the Americans depended overwhelmingly on technology, satellite surveillance, radio intercepts and so forth, a very little on human sources’.[cvi] Because technical sources tend also to be very ‘top secret’ and over-compartmentalised, one American military expert has commented that the products from these sources are difficult to sanitise and distribute, while also being put forward as a substitute for human assets, whose arrival is consequently delayed.[cvii]

Unconventional capabilities not normally considered part of the intelligence domain can yield a very good result for the operational commander. General Tony van Diepenbrugge focuses on two in particular: Radio Oksigen, a low-cost high-impact means of reaching youth in the 16 to 25 year-old range; and civil-military co-operation (CIMIC), used to improve relations with local populations, not only through humanitarian assistance, but through direct social contacts such as in the coaching of soccer teams. Both lead to the volunteering of militarily useful information.[cviii]

Another excellent source that can be tapped informally is that of the UN Military Observers (UNMO). Although not in the same chain of command and operating under a different mandate, they can be helpful.[cix]

However, in dealing with non-intelligence observers and collectors of Humint, it is essential to remember that they are not trained intelligence professionals, and their reporting could lead to both information overflow and misinformation. The force commander should endeavour to both provide some training to all of these individuals, and also sponsor a systematic debriefing program that can filter their knowledge within a professional intelligence framework.[cx]

The matter of training all personnel through and about intelligence merits emphasis. United Nations Training Assistance Teams (UNTAT) working at the Westdown Camp on Salisbury Plain are said to have made a considerable difference in the effectiveness of forces deployed to Bosnia. Such teams take time to develop.[cxi] In the Congo, a lack of proper orientation of patrols led to a massacre when a patrol did not understand that the Baluba tribesmen confronting it were dangerous and hostile, the patrol thought they were friendly, and their bows and arrows harmless. Only two survived.[cxii]

In dealing with national intelligence cells that are not obligated to give the commander anything, two factors can be used to improve access to intelligence: first, the principle of reciprocity, where the commander deliberately sanctions sharing and exchange; and personalities. Personal relations are vital to assuring a positive flow of both sensitive intelligence information among contingents, and commanders must be conscious of the importance of having the right personalities in the role of liaison officers.[cxiii] Renaud Theunens believes the UN should adopt the Military Intelligence Liaison Officer (MILO) concept of the United Kingdom,[cxiv] perhaps asking Member States to identify such individuals, and then providing, as General Cammaert and Van Diepenbrugge have suggested, a common base of training for this multinational capability. Theunens also proposes sharp limitations on independent national intelligence cells, and instead recommends that a Joint All Source Intelligence Cell (JASIC) be formed that is directly responsive to the Force Commander.[cxv]

National tactical collection capabilities will tend to be sensitive but they must be harnessed. Especially valuable, apart from traditional signals collection capabilities, are Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), which have ‘provided a relatively cost-effective and timely means to deliver imagery on high value targets.’[cxvi] Although the national contingents may initially resist, the establishment of centralised collection management and co-ordination, with a single focal point for each type of collection, is vital.[cxvii] The Baghdad Monitoring and Verification Centre (BMVC) is cited by one authority as an example of a success story.[cxviii]

The U-2 is now being made available to UN forces,[cxix] and C-130 imagery and signals intelligence platforms can also be requested from the Americans.

The commander should avoid becoming overly dependent on sensors and detectors. The commander will get good intelligence ‘…only by fully engaging the human factor in all steps of the intelligence cycle, focused on studying and understanding the attitudes and aspirations of all of the parties.[cxx]

Tactical intelligence is vital to the success of the mission ‘in detail’ and it is the foundation of the mission’s credibility. ‘If intelligence is not deftly handled, it is easy for the organisation to gain a reputation for being slow to react and for gullibility and political partiality’…counterintelligence may be necessary…[cxxi]

The figure below summarises operational collection options: [cxxii]

Figure 3. Information-Gathering Spectrum from Permitted to Prohibited

Finally, the commander can make a difference in the totality of the operational collection endeavour by fostering ‘complementary footprints’, which is to say, spreading the representatives from the various elements out so that no one place has a cluster of duplicative representatives. By dividing locations and developing a system to exchange information in a structured way, with fixed meeting and fixed agenda, the whole does become greater than the sum of the parts.[cxxiii]

Operational Processing

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are worth their weight in gold. Commanders should ensure that they not only have the GIS equipment, but also the $5 cables for connecting the GIS equipment to computers and printers.[cxxiv]

The availability of software for link-analysis and other automated data processing is a significant shortfall. In combination with the limited to non-existent ability of analysts within different contingents to leverage multiple databases from one location, the operational processing capability at this time is quite constrained. [cxxv]

Document exploitation is one area where information technology advances can be of considerable assistance to the Force Commander. In addition to equipping patrols with digital cameras whose images can be rapidly transmitted back to the intelligence staff, they should also be equipped with hand-held scanners that can copy and transmit selected sections of captured documents. For larger volumes of captured documents, the Force Commander should consider having a small specialist cell able to screen documents, dividing them into those that are of immediate priority and must be translated in the field; those that are of longer-term importance and should be scanned and transmitted to translators elsewhere in the world; and those that can be set aside.[cxxvi]

Until a UN intelligence structure is created, where reliable assessments can be created at each level and are trusted, there will be a tendency for intelligence information to either not flow at all, or flow without control, up and down and sideways. This threatens to swamp the few analysts at each level.[cxxvii] It would be helpful for the UN to devise an Internet-based means for entering and accessing all data, using commercially-available security, as a means of at least achieving two goals: one-time data entry with force-wide access; and automated storage and retrieval.[cxxviii]

Operational Analysis

‘…one or two really sharp officers are of more value to me as a force commander than having an intelligence section of fifteen people who are engaged in a ‘process’. That process tells me history, not implications, predictions, and expected belligerent Courses of Action (CAO’s) which I need to know.’[cxxix] Rank should not be allowed to inhibit the commander’s utilisation of the best available analysts.[cxxx]

‘…profile the personalities, monitor the bigger picture, know the history of the conflict, monitor the media and political scene, analyse motives’.[cxxxi]

‘The intelligence is not only fragmentary, it does not adhere to the rules of regular war. An example: a report about four tanks on a road, if analysed in the traditional way, would be interpreted as a reinforced platoon or a company that would constitute ‘only’ a reconnaissance patrol. In Bosnia in 1995, the same four tanks would have heralded a major offensive.’[cxxxii]

‘In traditional peacekeeping operations there is no enemy. Instead you have warring factions toward which you have to remain impartial.’[cxxxiii] It could be said that unlike normal political or military situations, where there is a given incumbent and an identified ‘enemy’, in peacekeeping situations there are no constants and no certainties, and the analysis challenge is much greater, every party must be viewed with equal suspicion and analysis must be applied to the plans, intentions, and potential course of action of all parties, whether armed, unarmed, hostile or friendly.

One potentially disruptive aspect of operational analysis will be the conflicting views that are generated by senior NATO officers who have access to national sources that may not be shareable with, for example, a Swedish non-aligned officer even if that officer is in charge of the force intelligence campaign.[cxxxiv] One means of dealing with this is to refuse private briefings, but to sponsor round-table discussions where NATO dissent or input is encouraged on an ‘informed opinion’ basis, without producing sources or specifics. This at least will ensure that all key force intelligence managers are sharing the same perspective on the battlefield.

The operational intelligence analysis effort must avoid being consumed with day-to-day intelligence requirements. Personnel, time, and resources must be set aside and protected, to focus on longer-term evaluations and assessments.[cxxxv] One experienced officer appreciates the distinctions of ‘basic-descriptive’ (fixed factors), ‘current-reportorial’ (recent and emerging), and ‘speculative-estimative’ (future assessments).[cxxxvi]

‘To understand a conflict like the one in the Balkans you have to learn the history, religion, cultures, and ways of thinking in the countries concerned. The lesson learned is that what is irrelevant in Stockholm and The Hague may very well be relevant in Pale.[cxxxvii]

‘Due to the nature of the conflict, the local power centres amalgamate military, economical, and political power. The objectives of the local parties are often determined by hard to quantify and qualify political and socio-cultural factors, which may appear irrational in our ‘Westernised’ judgement.’[cxxxviii]

Deliberate efforts to create a frame of reference or framework to which analysts can attach and test their ideas to identify patterns, are recommended. So also are role-playing and scenario development, with the caution that these efforts require the participation of many others, not just the staff analysts. Perhaps most importantly, once a scenario has been found to be plausible, it should be delivered to the contingent commanders and their staff in face-to-face mode, and explained properly so they can be alert to indicators that the scenario might be upon them.[cxxxix]

It is important, in conducting peacekeeping intelligence analysis, to very clearly understand that traditional military indicators are not the primary signals that must be perceived and integrated. Unconventional combatants do not drive tanks, they drive ‘technicals’, Toyota pick-up trucks with machine guns crudely mounted in the back. They do not wear uniforms. Over time the analyst will establish a sense of the different things to be looking for, and can promulgate to the tactical units and the varied human collectors a ‘playbook’ specific to the AOR.[cxl]

A Force Commander would benefit from instituting a feedback or evaluation loop on all estimative intelligence, seeking to determine over time how well specific analysts and specific predicted course of action came to pass.[cxli]

Operational Security

The Force Commander has a responsibility to protect the impartiality of the UN mission by ensuring that any information they collect on one belligerent is not inadvertently intercepted by another belligerent. For this reason, establishing reliable secure communications among the units and with higher headquarters is a significant command responsibility.[cxlii]

Among the specific counterintelligence aspects recommended by General Cammaert are a pre-deployment analysis of intelligence collection capabilities by the opposing groups, the assignment of a qualified counterintelligence officer to the headquarters staff; the assignment of a computer network information security specialists to the staff; the early integration of appropriate computer security hardware and software throughout the operational headquarters; and the inclusion of several field investigation/interviewing teams in the planned force structure.[cxliii]

As the UN gets involved in human rights monitoring and the prevention of genocide, it must be prepared to recognise and counter substantial efforts by belligerents who will place UN officials under human and technical surveillance, as happened, for example, in Guatemala in the 1990’s.[cxliv]

It is imperative that the Force Commander not under-estimate the ability of non-state belligerents to conduct sophisticated and pervasive human and technical intelligence operations against the UN peacekeepers. Many belligerent groups are able to draw on both direct government support (e.g. as occurred in the Croation-Serbian conflict when the West chose sides secretly) or sympathisers in First World countries who can procure advanced commercial systems; some terrorist groups have a higher ratio of electrical engineering Ph.D.’s than most governments; and some insurgent groups have such a strong will and strong work ethic that they can accomplish amazing feats, such as digging tunnels right up to the G-3 Operations Centre, placing either a human or a microphone directly beneath the chief’s desk.[cxlv]

Information security must be a constant aspect of the commander’s operational planning and execution.[cxlvi] ‘At all levels, one of the toughest lessons that UK forces had to learn in both Ireland and Bosnia was that of COMSEC.’ This challenge is complicated when forces deploy with poor equipment that will not work in urban areas, when forces substitute commercial cell phones for radios, and when the non-state belligerents are themselves highly sophisticated at technical collection, not just passive airwave monitoring, but active ‘bugging’ of force headquarters telephones and offices.[cxlvii] (NOTE: Force Commanders who feel that cellular telephones are an essential part of their communications flexibility may wish to consult the Finnish military and have them oversee the distribution of Nokia cellular phones with embedded encryption capabilities.)

‘Perception security’ might be a useful term for focusing attention on situations where the UN could be tainted or threatened by the behaviour of those it is supporting. In the Congo, for example, an individual under escort from the UN made such inflammatory statements that those he was speaking to assumed the UN shared his views, leading to an attack on a 90-man dispersed garrison, of whom 47 were killed.[cxlviii] The Force Commander must stress to all hands that they are responsible for constantly monitoring, interpreting, and reporting all that they see, especially when UN armed personal are publicly accompanying belligerent personalities whose actions or words might create an imminent threat to UN forces.

There is another aspect of security that must concern the Force Commander, and that is the necessity, if within the mandate, of training local security forces. Israeli experience suggests that only a local security service is truly capable of dealing with its own terrorists and crime bosses, but Israeli experience in observing American training of the Palestinian Authority also cautions that one must know who is being trained, many of those the Americans trained were, unbeknownst to them, former terrorists. Hence, the Force Commander should be planning for early reconstruction and revitalisation of local security services, but must also plan for intelligence and counterintelligence ‘vetting’ of everyone to be joined and trained.[cxlix]

The UN is not yet ready for another aspect of intelligence, that of covert negotiations that are secret from the media as well as other parties. As one contributor noted, in the Middle East, many moderate Arab leaders have paid with their lives for being known to be in dialog with Israel, and one benefit of a truly ‘secret service’ is that it can open doors that will not open in public.[cl]

Tactical Intelligence

Tactical intelligence in peacekeeping operations must more properly be considered tactical-operational or operational-tactical. Because of the political implications of every action, however minor, the contingent commanders must understand, and must direct their intelligence capabilities so as to emphasise, that the SRSG’s political objectives, and the Force Commander’s operational mission objectives, must be kept in mind at all times.

Tactical Collection

Peacekeeping intelligence collection is a bottom-up process, largely requiring that the tactical units collect and evaluate the indigenous order of battle ‘from scratch’.[cli] At both the tactical and the operational levels, a database of specific personalities will be most helpful to the Force Commander and the contingent commanders.[clii]

A major distinction between traditional tactical intelligence focused on organised armed and uniformed conventional forces, and peacekeeping tactical intelligence, is that political intelligence gathering becomes of paramount importance, not just the collection of what is said overtly, and the overt observation of behaviours and patterns that may often be at variance with what is said, but also the collection through whatever sanctioned means might be available, of what is said behind closed doors that may help the tactical commander and the Force commander understand plans and intentions.[cliii]

At the tactical level as well as the operational level, having peacekeepers perform a variety of unconventional civil affairs roles is helpful in collection, and these responsibilities should be entertained by the contingent and force commanders as opportunities rather than distractions.[cliv]

The ‘Mark I eyeball’ remains the most valuable tool[clv] and every peacekeeper must be trained to observe and debriefed in a timely manner. In addition to the human eye, the value of digital cameras and video recorders cannot be over-stated. With such devices scattered around the force and able to send images back to the operational level (or as appropriate, to New York), ‘the commander is already ten steps ahead in the game that he would otherwise be’.[clvi]

Military police and UN civilian police units should be regarded as human collection assets, and receive commensurate orientation, training, and debriefing.[clvii] NGO’s represent a different kind of opportunity. Here their reluctance to be tainted in any way must be respected, but their value cannot be ignored: their representatives ‘have generally been present in the region longer than UN forces, speak the languages of the countries involved, know and have the trust of local officials, and have a deeper perspective on the events surrounding them than UN forces’.[clviii]

Convoy drivers, patrols, and individuals who have been manning observation posts should all be part of a structured debriefing program.[clix]

Indeed, debriefing has been cited by most after-action reports and articles as one of the most important contributors to situational awareness at the tactical and operational levels.[clx] However, debriefing is labour intensive, and most force structures do not include sufficient dedicated interrogator-translator teams or funds for sufficient contracted translators (both expatriate and indigenous).

Patrolling is also a vital aspect of intelligence collection as well as public reassurance. One innovation that enhanced the security of patrols was that of covertly emplaced ‘overwatch’ teams able to observe large areas and warn the patrols of ambushes in preparation.[clxi]

Translators and ideally translators, who are not from the local area nor restricted by their clan association from free movement through the entire AOR, are extremely helpful. One American success story, a surprisingly unconventional solution borne out of desperation, was the use of contracted Somali interpreters, many of them taxi drivers by trade, who were able to provide reliable unbiased translations, and interpretations of body language (both ways).[clxii]

As a general rule, overt human intelligence will be extremely important to the tactical commander.[clxiii]

Tactical Processing

Patrol reports and other tactical observers must be debriefed and evaluated as quickly and efficiently as possible. At the tactical level most of the processing is labour-intensive, and staffing should be allocated accordingly. For example, although the battalion intelligence staff can and should conduct debriefings on occasion, it is much more effective to have several professional interrogator-translator teams, each equipped with laptop computers and secure means of sending digital reports.

Tactical Analysis

Irrespective of whether the peacekeeping force is invited or intrusive, tactical units must never take any information offered by any ‘host’ official or any ‘friendly’ party at face value. At the same time, whatever covertly obtained intelligence that may be received from ‘on high’ must be treated with equal suspicion. ‘National Intelligence can be wrong, and can certainly be out of date’.[clxiv]

Tactical intelligence collected in isolation from history, culture, and context will be largely irrelevant to the outcome. Among the most important lessons learned (and then promptly forgotten) by the Americans in various peacekeeping operations, are the vital necessity of understanding the culture, who (precisely) makes the decisions, how the infrastructure is designed, and the specific values and taboos.[clxv] Somalia, for example, will stand for a very long time as an example of the cost of failing to understand sub-state tribal or clan power structures, interests, and intentions.

Tactical Security

Bad things happen in multiples. The American practice of sending CRITIC messages when special events occur (such as a suicide bombing against the Marine barracks in Beirut) could be usefully emulated by the Force Commander. Had there been a similar local area warning network in place, the suicide bombing of the French barracks later on the same day might have been averted.[clxvi]

The issue of warning from higher and adjacent commands is one that merits new doctrine and new methods. At this time most national-level warnings are so imprecise (and sometimes so frequent) that ‘warning fatigue’ occurs. It may be worthwhile to have one individual assigned exclusively to the task of filtering and considering warnings in the local context, while also pursuing every liaison opportunity to collect on any indications or warning notices that might be made available.

Sometimes, military regulations can place peacekeepers at risk. American regulations in Bosnia, for example, required all personnel, including overt human intelligence collectors, to wear full battle-dress, carry shoulder weapons, and travel in conspicuous four-vehicle convoys.[clxvii] The Force Commander must promulgate reasonable ‘rules of engagement’ for human collectors that enhance their safety through a reduction of their conspicuousness. Long hair, beards, and local transport can often be superior to bullet-proof vests, and are a required accommodation for selected personnel with collection responsibilities under low-intensity asymmetric warfare conditions.

Concluding Observations

Millions more will die as the great powers compete with one another or vie to fulfil the personal visions of their leaders, some of whom have little regard for the views and concerns of the majority of the global population. In this context, the United Nations stands alone as the universal organisation whose potential for enhancing global security and prosperity is unrivalled. The challenges, however, are great, and the financial and military and civilian personnel resources are small.

Intelligence qua knowledge; intelligence qua understanding; intelligence qua networked minds harnessed for the common good; intelligence converted into public wisdom and shared perceptions, may prove to be the missing element whose absence has constrained UN effectiveness.

The Brahimi Report is the perfect catalyst for promptly establishing a new UN acceptance of and exploitation of the proven process of intelligence as a legal, ethical, professional means of collecting, processing, analysing, and keeping safe such information as might help the UN leadership establish the correct mandates, establish the correct force structures, and fulfil every peacekeeping mission with precision.

As a group, we are all in agreement. The UN should immediately establish a strategic intelligence secretariat consisting of the very highest calibre of people with direct access to funds for the purchase of open sources of information. The UN should devise an operational intelligence concept of operations that includes increased availability of various standing packages from the Member States and perhaps regular PKI exercises among varied elements. Finally, the UN should immediately commission the creation of a UN intelligence training curriculum, to be offered both as a residency course and as a mobile training course. The way is open for ‘UN intelligence’.

Endnotes