Is open hardware creating a more open world?

Is open hardware creating a more open world?

Feature | April 25, 2012 | By Adrian Giordani

international science grid this week

Just as retro ideas from a bygone era can inspire modern fashion, film, and TV trends, today’s researchers are being empowered by the revival of an innovative technology concept from the past: open-source hardware.

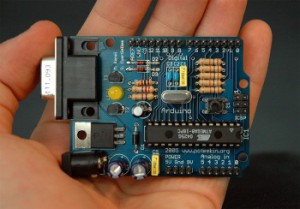

Open-source hardware is the public availability of designs, mechanical drawings, or schematics of physical technology, such as computer processors or network switches. The Arduino electronics board is one popular example.

The concepts behind open hardware have been around for decades. But, with the rise of intellectual property in the 1980s and 1990s, open hardware fell out of favor. Today, perhaps thanks to the success of the open-source software movement, open hardware is back, according to its proponents. In 2012, it allows researchers to measure the time-of-flight of neutrinos, enables poor rural communities to communicate freely, and creates new business markets.

Checking neutrino speeds once and for all

This is an Arduino RS-232 serial communication board interface. It is an open-source programable microcontroler designed to make using electronics more accessible and for any number of applications that a user can think of. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

“By going public, we can find experts to solve problems we cannot,” said Javier Serrano, an accelerator engineer at CERN.

Serrano founded CERN’s Open Hardware Repository three years ago. It’s an online forum with around 50 projects; anyone, inside or outside of CERN, is free to collaborate on the repository’s hardware projects.

The first non-CERN project that joined was Reconfigurable Hardware Interface for Computing and Radio (RHINO). It helps various people collaborate to design circuit boards, FPGAs (field-programmable gate arrays), and software for radar signal processors.

“Open-source hardware is making a significant impact to large-scale science. I hoped to gain support in the development of RHINO, which Javier and his team happily provided,” said Alan Langman, an electronics engineer from the University of Cape Town, South Africa,who leads the project. “RHINO was motivated partly by the Collaboration for Astronomy Signal Processing and Electronics Research project, out of the University of California, Berkeley. This is a large international and open collaboration, the fruits of which have enabled many radio astronomy instruments. For example, Matthew Bailes from Swinburne University, in Australia, used CASPER to discover numerous pulsars.”

CERN’s White Rabbit Project is another example of science that is benefitting from the OHR. WRP is helping researchers to verify that neutrino particles do not travel faster than the speed of light. Last year, the time measurement was made by using GPS (Global Positioning System). In May this year, another short-pulsed beam will be sent from CERN to Gran Sasso to confirm results once and for all.

At the same time, independent verification will also take place: both fiber optic cables and atomic clocks are being used. Serrano is leading a team to double-check the time-of-flight of neutrinos.

The team will improve the synchronization system inside the labs at CERN and Gran Sasso by controlling the transmission delay of signals in fiber optic cables connected to GPS receivers.

Initially, eight kilometers (five miles) of fiber optics will be tested. Eventually, more than 1,000 nodes across 10 kilometers (six miles) of fiber optic cables will be synchronized to an accuracy of one billionth of a second.

Serious time nuts

The ‘time nuts' working with Javier Serrano are made up of a group of amateurs who are interested in precise time & frequency. Topics they cover include the stability of quartz oscillators, and measurements of rubidium and cesium atomic clocks. This is an example of their attempt at a first atomic wristwatch. It is a self-setting, radio-controlled, atomic-time, wrist watch that is never off by more than a second or two a day according to their website. Image courtesy Leapsecond.com.

Serrano is also teaming up with researchers outside of CERN via a collaborative forum to use atomic clocks as a measurement independent of GPS. These ‘time researchers’, more affectionately known as ‘time nuts’, are individuals who see time as their hobby. But these ‘hobbyists’ are a far cry from someone tinkering in a garage.

“These researchers have atomic clocks in their homes more accurate than some national institutions,” Serrano said.

Tom van Baak, a software engineer by day and a time nut by night, is among Serrano’s team members. Van Baak wanted to test whether gravity alters time, as predicted by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity; he did so by grabbing several cesium clocks from his home-made timing laboratory and driving up a US mountain with his children. His clocks showed an average time dilation of approximately 23 nanoseconds, which was in keeping with general relativity.

This spring, Serrano plans to drive this crack team of time nuts, and their clocks, all the way from CERN to Gran Sasso.

“Our collaboration with researchers with an independent interest in time measurements was only possible because we went public with our project. Interested specialists can join our mailing list too. We’re working with interested individuals and also the commercial sector,” Serrano said.

Empowering the niches

Commercial companies benefit from open-source hardware too, because they get access to new markets and hardware designs.

“We can take part of large projects we would not be able to drive alone. We hope to spin-off some of the developments done at CERN into other potential markets,” said Eduardo Ros, head of research and development at Seven Solutions.

Seven Solutions is a commercial engineering design company that works with science and industry. It’s a partner in WRP and is building an Ethernet extension switch that will enhance the accuracy of measuring different particle speeds.

“Imagine we design hardware with a potential market of thousands. A commercial company doesn’t want to risk a year’s worth of investment to develop this same hardware. We could give them our designs, so there is no research and development cost for the company,” Serrano said. “IBM already has a hybrid model where they make a living out of selling proprietary and open-source computers in one package. Their hardware is proprietary, but it includes Apache open-source webserver software.”

The poorest of people are also benefiting. Open hardware is helping connect rural African communities, where phone tariffs are expensive.

Below is an introduction to the Village Telco project. a social enterprise to enable affordable communication to everyone and available everywhere. Village Telco created a device called a Mesh Potato. It was named so because its designers needed a wireless mesh device to which a Plain Old Telephone Service (POTS) phone could be connected via an Analog Telephone Adapter (ATA). These acronyms combined with the word ‘Mesh’ makes ‘Mesh Patata’. Patata is Spanish for potato, hence the name Mesh Potato. Image courtesy Village Telco.

The Village Telco project has created a cheap and partially open-source device, with a range of between 300 and 400 meters, that enables anyone to communicate freely over a Wi-Fi network using a phone. The device is called a Mesh Potato.

“We weren't thinking that much about open hardware when we started. Our priority was simply creating affordable access in Africa,” said Stephen Song, who founded the project.

Since 2011, 1,500 Mesh Potato devices have been sold in almost 30 countries.

“We’ve also had interest from companies in South Africa, interested in manufacturing the Mesh Potato, and from others interested in white label-branding the device,” Song said.

The product’s users have shown just as much creativity as its inventors.

“We did not foresee the demand for alternative infrastructure in crisis situations. Neither were we thinking of refugee or IDP (Internally Displaced Person) camps,” Song said. “Farmers or resort managers in remote areas use it as a means of managing local communication over their estates.”

Song foresees the unused ‘white space’ that sits between TV channels, known as the Television White Space Spectrum (TVWS), as a frequency range for which a new Mesh Potato device could be made.

“We look forward to the growth of the TVWS as a new opportunity for low-cost devices using an unlicensed spectrum,” Song said. “This could create an opportunity for a TVWS Mesh Potato, which would have substantially greater range.”

A cheaper second generation Mesh Potato will be available later this year.

“We're believers in the power of ‘open’, and our next generation Mesh Potato will be fully compliant with the Open Hardware definition 1.0,” Song said.

Is free beer or free speech more important?

2012 is absolutely the year for open-source hardware,” said Alicia Gibb, a technology researcher.

Ayah Bdeir, an engineer based in New York, New York, is one of the co-founders of the Open Hardware Summit, which he describes as“a huge success and pillar to propel the movement forward.” The next summit is on the 27 September 2012.

Bdeir is the creator of the littleBits product– essentially LEGO for electronics – who helped develop the Open Hardware definition 1.0.

“This license is to hardware what the GNU General Public License is to software,” Bdeir said.

This definition was used as a framework by CERN to develop its own Open Hardware License for the OHR in July 2011.

“2012 is absolutely the year for open-source hardware. More people are adopting our logo. Also, venture capitalists are funding lots of start-ups,” said Alicia Gibb, a technology researcher who caught the open-source hardware bug when working for a US company called Bug Labs in 2008. She helped start the summit with Bdeir in 2010.

Gibb is now on a mission to set up an open-source hardware association – a place where standards can be developed under one roof.

The Open Source Hardware logo silkscreened on an unpopulated PCB (Printed Circuit Board) Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

“As we become more formalized, there’s a challenge in creating helpful standards. Standards are usually limitations so we use the words ‘best practice’ instead. Eventually, we want to go to bigger organizations to get support and convince them to build open products,” Gibb said.

The phrase, ‘free as in beer or free as in speech’ is well-known in the open source software community. When something is free as in beer, the user gets the beer for free, but no one tells them how the beer is made, and they aren’t being invited to make suggestions on how to improve the recipe.

In contrast, when something is free as in speech, users can access a product’s source code, and collaborate with developers and other users to improve it, and – in some cases – re-distribute an entirely new version of it. However, although the unscrupulous user can use the open source software for free, they do not necessarily have the legal right to do so. Many products that are free as in speech are also free as in beer, but not all. To the uninitiated, this approach may seem strange, but it enables a world of enthusiasts and experts to freely volunteer their expertise to improve a centralized product.

“In the distinction between free beer or free speech, I’m more concerned with the latter [for open-source hardware],” Serrano said. “We try to avoid vendor-lock-in situations. Companies can still be profitable. Much of the best software is open. Open hardware provides a fair environment in which companies can compete to be chosen on the basis of competence, quality of service, and price.”