By VANESSA M. GEZARI

New York Times, August 10, 2013

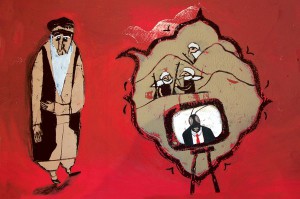

ON a sunny, crisp November day in 2008, three American civilians joined a platoon of United States soldiers on a foot patrol in Maiwand District, a flat, yellow patch of earth crowned by black-rock mountains in southern Afghanistan. The civilians were part of the Human Terrain System, an ambitious, troubled Army program that sends social scientists into conflict zones to help soldiers understand local culture, politics and economics.

That day, the team planned to interview shoppers coming and going from a nearby bazaar. Afghans had complained about the high price of flour, so the Human Terrain Team members were creating a consumer price index. They also wanted to find out whether Afghan officials were asking shopkeepers for bribes, and how merchants protected themselves and their goods in a place where insurgents and local security forces threatened civilians in equal measure.

The team’s social scientist that day was Paula Loyd, a 36-year-old Wellesley graduate and Army veteran with degrees in anthropology and diplomacy and years of experience as a development worker in Afghanistan. Through her interpreter, she struck up a conversation with an Afghan man who was carrying a jug of fuel, asking how much he had paid for it. They talked genially until her interpreter was called away. Suddenly, the man doused Ms. Loyd with gas from his jug and lit her on fire.

It was one stunning act of violence in a conflict that has killed more than 2,100 American troops and wounded more than 19,000. As the United States drawdown approaches, stalled peace talks with the Taliban, Afghan political maneuvering and the waste of billions in taxpayer dollars dominate headlines. Each new attack stokes our yearning for a quick exit. But the more assiduously we seek to put the pain and hard-won lessons of this conflict behind us, the more likely we will be to repeat the same mistakes in the next war.

Paula Loyd died of her injuries a few months after the attack, in January 2009. Soon after, I flew to Kandahar to try to figure out who had set her on fire, and why. It seemed obvious that the Taliban were behind it, but the assault was unusual, to say the least. She was unarmed, interviewing people and taking notes, something I’d often done in villages around Afghanistan. I couldn’t remember a Taliban attack that resembled it. Neither, it turned out, could anyone else.

Over the next two years, I would hear nearly a dozen accounts of what had motivated Ms. Loyd’s assailant. (He couldn’t tell me why he did it, because minutes after the attack, he was shot by one of Ms. Loyd’s grief-stricken colleagues.) The stories often conflicted, but each one illuminated the crisscrossing narratives of the war. I spent my formative years as a journalist in Afghanistan, and reporting there taught me something that would pass for heresy in many American newsrooms: finding the truth is not just about gathering facts. It is also an interpretive and imaginative effort.

Afghans have a knack for the nonliteral. They value stories for reasons that have nothing to do with the practical information they contain. In his recent memoir, “A Fort of Nine Towers,” Qais Akbar Omar writes of a Dari literature teacher who helped him see that “there is more to a story than its plot. She told us that images created by words can have hidden meanings.” The scion of a prosperous Kabul family, Mr. Omar is that rare Afghan lucky enough to have grown up in a house full of books.

In the countryside, where three out of four Afghans live, some 90 percent of women and 63 percent of men cannot read or write. Afghanistan is a predominantly oral culture, where stories may be read aloud once, then memorized, told and retold, changing slightly or significantly with each telling. The door between literature and everyday language has long been ajar; even in casual exchanges, Afghans rely on allegory, metaphor, parables and jokes to convey meaning.

Such indirection is common in violent and repressive societies, but after more than 30 years of war, the Afghan penchant for elegant and oblique expression is particularly well honed. Stories give the teller power over the chaos that surrounds him. They are also a kind of code. Knowing how to read them separates Afghans from the people known in Dari as haraji, outsiders — namely, everyone else.

American soldiers often fail to make sense of these stories, or simply dismiss them as meaningless. They’re nothing like the Excel spreadsheets and acronym-heavy briefing slides that military people are trained to read. A prime example is captured in a brilliant video by the photojournalist John D. McHugh for The Guardian. In 2008 near the Pakistani border, an American sergeant becomes convinced that the rockets plaguing his men are being fired from a ridge just outside a nearby village. He marches into the sandy hamlet in search of answers. An Afghan translator flags down a red-bearded elder, who gestures toward the nearby mountains.

“The Taliban are over there — not far away,” the old man says in Pashto. “I would like to tell [the Americans] a story. In our country, we grow wheat and we have ants. There is no way we can stop the little ants from stealing the wheat. There are so many little ants it is almost impossible to stop them. I’ve told this story to help the Americans understand the situation in Afghanistan.”

The American sergeant, waiting, shifts uneasily. “He’s giving many examples,” the translator finally says. “The main point is that if you want to get the [Taliban] they are behind this road, behind this mountain.”

The video is about the perils of inaccurate translation, and indeed, the translator fails mightily. But it’s worth asking what the sergeant would have made of the story had it reached him. The Afghan is saying something crucial about the inseparability of insurgents from everyone else, and about the dangers of fighting in the weeds, where bullets can strike the wrong targets, like pesticides that kill the very crops they’re designed to protect. The story might not supply coordinates for an insurgent safe house, but it certainly helps an attentive listener understand what the world looks like to a villager in a contested part of the country.

GOOD intelligence requires good reading; you can’t have one without the other. Paula Loyd understood this. Years earlier, in her anthropology honors thesis at Wellesley, she described how marginalized people — servants, slaves, women in male-dominated societies — quietly pushed back against the dominant social order. Drawing on the work of the Yale political scientist James C. Scott, she wrote that they tended to be “cautious about expressing their resistance openly when they perceive the power of the dominant group to be very strong.” But “when they are among their own, the peasants carry on an entirely different dialogue.” In such situations, she observed, people talk in “jokes, metaphors, folk tales, and codes,” artfully conveying meaning while preserving maximum deniability.

For years before Paula Loyd landed in Maiwand, the United States had been mismanaging the political situation in southern Afghanistan, ignoring the poor and powerless and propping up local commanders who exploited them. Her clarity about the subtle, indirect ways people talk in dangerous times was part of what made her such an asset. There weren’t enough like her.

The Human Terrain System sought to bring a degree of anthropological and interpretive acumen to a military that badly needed it. But it came too late, alienated too many anthropologists and was thrown together too quickly and sloppily to achieve many of its goals in Afghanistan. Taxpayers have spent more than $600 million on the deeply flawed program; it has occasionally benefited soldiers, but its slipshod construction and murky aims have also put Afghans and Americans at risk. Today, 14 Human Terrain field teams remain in Afghanistan, down from a high of 30; as more American troops leave, the teams will go with them. Policy makers should seize this moment to overhaul the military’s cultural-knowledge efforts.

What happened to Paula Loyd reminds us that understanding what motivates our enemies and the people we’re fighting among is a long and painful undertaking. But turning away from this effort, as many in the military did in the wake of Vietnam, ensures only that more Americans will die in other wars, in other far-flung corners of the world.

Tip of the Hat to the NYT. This article is so important to our comrades that we have taken the rare liberty of providing the entire piece (our readers do not like to click through). Read the original here.

Phi Beta Iota: The “seven sins” of US national security and foreign policy and operations are still with us. In Afghanistan the war has been fought to use up men and machines, not to actually accomplish anything of lasting value (such as reliable scalable infrastructure that can be operated and maintained by the Afghans themselves. Now, in what is really the last year of the war, the US and NATO (ISAF) leadership not only have to learn everything their predecessors failed to learn, but they also have to transition, in one year, from being an occupying force to being a much reduced military assistance group with zero political voice (and no CIA cash for politicians) — while the commander flushes out the spies (going to meetings in convoys surrounded by guys with too much ink) and instead ramps up diplomatic commercial and technical attaches to start pumping US commercial and mineral visitation pre-cleared with all sides and assured safe passage by all sides. Perhaps most importantly, the US leadership in both Afghanistan and Washington and Belgium needs to learn that the one word they cannot use in any public presentation is “win.” We did not win. We lost. Anytime General Allen or anyone else claims we won, the Taliban do an attack or driven car bomb in the middle of Kabul to remind those left behind that we have not won. Injudicious words at the strategic level kill our comrades at the tactical level. The Taliban is a decade ahead of us in strategy, and by most informed accounts, seeks from the USA nothing more than honorable intent and a commitment to draw down quickly and responsibly while staying out of internal politics. There is money to be made in Afghanistan from minerals including rare earths, and from building infrastructure against the Afghan revenue from those rare earths. The sooner the Americans focus on a seamless transition, the sooner they can accomplish that transition.

Side note: Beware of Fairfax County Afghans. A MAJOR challenge in the transition period will be the fine-tuning and monitoring of the attitudes of the translators, the embedded contractors, and the troops themselves. This is not about going forward anymore, this is about going in reverse and striving to get to “park.” Walk in peace, with honorable intent.

See Also:

Review: Making Friends Among the Taliban

Review: Surrender to Kindness (One Man’s Epic Journey for Love and Peace)

Review: Taliban — The Unknown Enemy