I rely on Nicholas Carr to be the fly in the ointment to all things hailed as utopian about the Internet. The critic's view of the online learning “revolution”.

The Crisis in Higher Education

Online vesion of college courses are attracting hundreds of thousands of students, millions of dollars in funding, and accolades from university administrators. Is this a fad, or is higher education about to get the overhaul it needs?

Nicholar Carr

MIT Technology Review, 27 September 2012

Phi Beta Iota: This is a better overview article than those previously posted here.

A hundred years ago, higher education seemed on the verge of a technological revolution. The spread of a powerful new communication network—the modern postal system—had made it possible for universities to distribute their lessons beyond the bounds of their campuses. Anyone with a mailbox could enroll in a class. Frederick Jackson Turner, the famed University of Wisconsin historian, wrote that the “machinery” of distance learning would carry “irrigating streams of education into the arid regions” of the country. Sensing a historic opportunity to reach new students and garner new revenues, schools rushed to set up correspondence divisions. By the 1920s, postal courses had become a full-blown mania. Four times as many people were taking them as were enrolled in all the nation's colleges and universities combined.

The hopes for this early form of distance learning went well beyond broader access. Many educators believed that correspondence courses would be better than traditional on-campus instruction because assignments and assessments could be tailored specifically to each student. The University of Chicago's Home-Study Department, one of the nation's largest, told prospective enrollees that they would “receive individual personal attention,” delivered “according to any personal schedule and in any place where postal service is available.” The department's director claimed that correspondence study offered students an intimate “tutorial relationship” that “takes into account individual differences in learning.” The education, he said, would prove superior to that delivered in “the crowded classroom of the ordinary American University.”

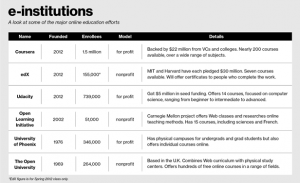

We've been hearing strikingly similar claims today. Another powerful communication network—the Internet—is again raising hopes of a revolution in higher education. This fall, many of the country's leading universities, including MIT, Harvard, Stanford, and Princeton, are offering free classes over the Net, and more than a million people around the world have signed up to take them. These “massive open online courses,” or MOOCs, are earning praise for bringing outstanding college teaching to multitudes of students who otherwise wouldn't have access to it, including those in remote places and those in the middle of their careers. The online classes are also being promoted as a way to bolster the quality and productivity of teaching in general—for students on campus as well as off. Former U.S. secretary of education William Bennett has written that he senses “an Athens-like renaissance” in the making. Stanford president John Hennessy told the New Yorker he sees “a tsunami coming.”