I regret that the considerable efforts of Jacqueline Nebel and Nadia McLaren are not mentioned — without them the volumes would not have emerged. Still, this is a wonderful article, I can only hope that it attracts some funding to continue the effort.

WSJ.com – Encyclopedia of World Problems Has a Big One of Its Own

Encyclopedia of World Problems Has a Big One of Its Own

Chronicle of Woes From Alien Abductions to Dandruff Finds Itself Short on Funds

Daniel Michaels

Wall Street Journal, 11 December 2012

Click on Link Above to Read Original. Safety Copy to Honor Judge Below the Line.

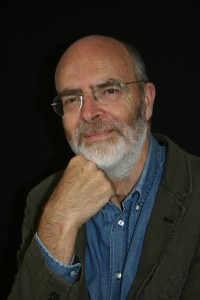

BRUSSELS—Anthony Judge's career has been peppered with problems, from Aarskog Syndrome to Zoonotic bacterial diseases. In between, he tackled dandruff, ignorance, kidney disorders and sabotage.

Mr. Judge, now semiretired, spent more than two decades editing the Encyclopedia of World Problems and Human Potential, a 3,000-page tome with almost 20,000 entries. The compendium of quandaries doesn't just list problems, it also faces one: money troubles. Its last print edition ran in 1995 and an online version is rarely updated. Yet its producers see potential to resurrect it.

The encyclopedia was Mr. Judge's brainchild when he helped run the Union of International Associations, a century-old grouping of groups that began in an effort to categorize all human knowledge.

The Union, which is less a union than a research institute, tracks more than 65,000 transnational groups including United Nations, the United Elvis Presley Society and the Hell's Angels. Its yearbook of them, first printed in 1910, now tops 6,000 pages of dense print in six hardcover volumes, for $3,080.

The UIA also organizes conferences to help organizations such as the European Coil Coating Association and the International Congress on Ultrasonics promote themselves in the cutthroat businesses of organizing conferences and managing associations.

It was the UIA's knowledge of organizations that in 1972 spawned the encyclopedia, after Mr. Judge and a friend got infuriated by a think-tank report that reduced the world's problems to just six issues. Mr. Judge believed his association of associations could better tackle the problem of problems because many groups exist to resolve concerns in areas such as health, human rights and development.

“There was money in problems,” recalls Mr. Judge, a 72-year-old Australian who was born in Egypt. “We didn't include flatulence for a laugh—incontinence is big business.”

That profit focus, though, masked an idealism about solving mankind's problems that dated back to the UIA's Belgian founders. One, pacifist campaigner Henri La Fontaine, won the 1913 Nobel Peace Prize—just months before World War I erupted.

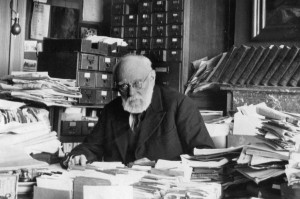

The other, bibliophile Paul Otlet, promoted peace through shared information. Humans would face fewer problems if they communicated more, he believed. One of his many books is subtitled “The Book on The Book,” and he later mused on “the problem of problems.”

In the 1920s, the two men created a vast collection of documents and objects in Brussels called the Mundaneum, which translates roughly as “worldseum,” that they wanted to make globally accessible by telephone.

Before all that, the duo tried to unite humanity by uniting the new international associations that were uniting people across borders. In 1910, they launched the UIA.

World War II decimated the Mundaneum but the UIA resumed its efforts to unite humanity and solve problems. Working from a 16th-century Brussels palace, the staff relaunched the yearbook of organizations, and, in 1954, it created an annual calendar of international congresses. It even launched a congress of international congress organizers.

In 1972, as work began on the encyclopedia, the Union became an early user of computers to compile data, track trends and seek associations among associations and problems that fascinated scholars. It also raised eyebrows during the Cold War. “We were interviewed by KGB front men and CIA front men,” recalls Mr. Judge.

UIA analysis revealed links that had been easily hidden before database searches, such as ties between religious groups and apparently independent companies, says Joel Fischer, an American who now heads the UIA's congress department. UIA archives still hold angry letters from lawyers threatening suits over the revelations.

When Mr. Fischer first visited the UIA in 1995, the bookish operation reminded him of the film “Three Days of the Condor,” in which the staff of a covert Central Intelligence Agency office in New York get assassinated after unintentionally uncovering a spy plot.

“What have I just walked into?” Mr. Fischer recalls thinking. “My wife is still convinced I work for the CIA.”

The encyclopedia let Mr. Judge and his colleagues chew over links among problems. “Which is economically more important: rust, wrinkles or refugees?” Mr. Judge recalls wondering.

To illustrate relationships, he experimented with graphics. The first encyclopedia, published in 1976, included a chart resembling a multicolor spider's web, titled “Mapping Societal Complexity.” Viewed through 3-D glasses tucked into the volume, “it was totally cutting-edge,” recalls Mr. Judge.

Listing “Abduction by extraterrestrials” near “Abortion-related deaths of mothers” drew charges of trivializing serious issues, but Mr. Judge says the encyclopedia simply profiled perceived problems. “We weren't out waving its flag,” he says of UFO kidnappings.

Many critics lauded the encyclopedia's ambitions, but others were bemused. “Obviously, it's not for the person looking for something light to read at the beach,” noted a 1991 review.

By its third edition in 1995, the encyclopedia focused as much on solutions as problems, the “human potential” part of the title. In the late 1990s, the European Union tapped the encyclopedia for part of an ecology project, and other multilateral institutions talked with the UIA about capitalizing on its database of problems. Global economic woes killed those plans.

In 2000, the UIA posted a version on the Internet. But then financial troubles and personal squabbles arose in the UIA, and the encyclopedia foundered. Yet the Web version “is still attracting interest,” says Mr. Fischer. “If somebody's got a problem and they're looking for answers, they'll come across it.”

UIA Secretary-General Jacques de Mevius says he hopes soon to relaunch the online encyclopedia. Inexpensive web technologies and wikis, developed since the last encyclopedia printing, could bring a makeover within the UIA's means, officials say. “Problems don't age,” says Tomáš Fülöpp, a UIA veteran who still advises the organization. “There's no resource like it out there.”

Mr. Judge, who retired in 2007 and now publishes a website with views on almost any subject, sighs at the encyclopedia's fate. “Doing this is mad,” he said, tapping a copy. “Possibly, like the Mundaneum, it's a historical curiosity.”