2011 THINKING ABOUT REVOLUTION

Robert David Steele

Intelligence Program, Marine Corps University, AY 1992-1993

Updated to Include Pre-Conditions of Revolution Graphic for USA Today (2011)

Drawn from 1976 Thesis: Theory, Risk Assessment, and Internal War: A Framework for the Observation of Revolutionary Potential where all appropriate citations and data operationalizations can be found.

Full Text Online for Ease of Automated Translation

Introduction

This article presents a brief overview of a theory of revolution and provides a concise framework for the evaluation of revolutionary conditions.

There are many who would maintain that there is no theory of revolution, and there is no general agreement on such basic elements of theory as terminology, definitions, and the kinds of data that should be collected in order to support a topology of revolution. Many works on revolution, relying heavily on the historical case study method, also fail to reconcile an array of partial theories.

Early scholarship essentially distinguished between the naturalist and the romantic concepts of revolution, with a realist concept emerging in the 20th century.

— The naturalist concept, the earliest concept, stemmed from the association of the word “revolution” with astronomy, where the cyclical and systematic movements of the stars suggested both an inevitability to political and social changes, and a revolving process in which a government that fell one year might easily return the next.

— The romantic concept came into being when men discovered their ability to alter the course of their development by intervening in the affairs of state. The emphasis in this concept was placed on the subjective inclinations of “man as the master of history” by virtue of his “heroic, romantic deed(s).”

— The realist concept reflects a relatively new sensitivity to objective conditions combined with a continued recognition of the importance of subjective elements which must be present if the objective conditions are to culminate in a successful revolution. To this extent, the naturalist concept (the inevitability of objective conditions) and the romantic concept (the necessity for human motivation) are combined.

Early scholarship and its simplistic approaches to the phenomenon of revolution were increasingly called into question as the world grew more complex. This article, after reviewing the elements of theory, provides a summary of a theory of revolution, and a basis for studying the preconditions and precipitants of revolution in a number of related but sometimes distinct spheres: political-legal, socio-economic, ideo-cultural, techno-demographic, and natural-geographic.

Elements of Theory

There have been three general (but partial) approaches to the study of revolution; none has provided an over-arching theoretical foundation able to accommodate the universe of revolution.

— Group conflict approaches, which include the partial theories of group differentiation and class conflict, suggest that the essential cause of revolutionary upheaval is either the incompatibility of the goals of two or more different groups; or the perception on the part of any group that it does not possess a sufficiently proportionate share of the available resources (political power, economic wealth, social prestige, cultural coherence) vis-à-vis other groups.

— Social-psychological approaches have been popular, emphasizing individual perceptions of relative deprivation. The psychological approach includes five separate mini-theories, those of social isolation, cumulative deprivation, relative deprivation, rising expectations, and status inconsistencies. While these all share an appreciation for socially-induced discontent as a precondition for collective violence, each reflects a different conception of precisely what kinds of social conditions and processes of change will lead to enough social discontent to cross the threshold of violence.

— Socio-structural approaches emphasize the importance of shared value systems and properly integrated subsystems. Stress is placed on the structural manner in which a social system continues to fulfill its functions in the face of change.

Early attempts to discuss the need for a theory of revolution, led by Harry Eckstein of Princeton, focused on four pre-theoretical gaps which must all be addressed if a theory is to be developed:

— Delimitation consists of restricting the scope of the inquiry by agreeing on the boundaries of the subject; i.e. which phenomena it will and will not include. Successful delimitation must both identify a homogeneous set of cases, and limit the degree of homogeneity requires for a case to be included in the universe under study.

— Classification pursues the pattern broadly established by delimitation, attempting to sub-divide the considered phenomena into classes about which both common and separate generalizations can be formulated. Classification is intended to reduce ambiguities and permit the creation of a topology. There are two types of classification: concrete, based on actually experienced and studies types; and ideal, composed of logically satisfying types.

— Analysis is the division of the subject into its basic components, the development of basic descriptive categories within which all aspects of revolution may be explored.

— Problemation, a word coined by Eckstein, addresses the nuances of the topic, to include discussion of general frames of reference, the distinction between preconditions and precipitants of revolution, the processes and techniques of revolution, and the outcomes and long-term consequences of successful or unsuccessful revolutionary effort.

This article, based on a graduate thesis, provides the theoretical framework within which to evaluate revolution as a phenomenon—a framework within which to classify kinds of revolution and examine the basic questions of what (dimensions of revolution), why (aspects of revolution), where (preconditions of revolution), when (precipitants of revolution), and who & how (the revolutionary process.

Change and Revolution

It is not possible to define revolution without first establishing an understanding of change. The following chart, using aspects of change identified by Ted Gurr, but adding specific levels of distinction for each, is an essential foundation for defining revolution.

1. Type of Change

- Political

- Legal

- Social

- Economic

- Ideological

- Cultural

- Technological

- Demographic

- Natural

- Geographic

- Military

2. Extent of Change

- Negligible

- Moderate

- Significant

- Severe

- Catastrophic

3. Scope of Change

- Contained

- Scattered

- Pervasive

4. Pattern of Change

- Random

- Sporadic

- Persistent

5. Rate of Change

- Slow

- Steady

- Fast

- Rapid

Figure 1. Aspects of Change

Now, having established a sense of what constitutes change, the subordinate aspects of revolutionary change can be described, and a definition of revolution gradually achieved.

WHAT: Dimensions of Revolution

One must understand the differences between several broad dimensions within which revolution can occur; as will be outlined when the topology for study is presented, revolution can occur in one dimension without necessarily affecting others.

Political-Legal

Socio-Economic

Ideo-Cultural

Techno-Demographic

Natural-Geographic

Figure 2. Dimensions of Revolution

The political-legal dimension refers to the rights and duties of the inhabitants of any given organization—who governs whom, and to what end. Included as items for observation would be the character of the elites, if any; priorities manifest in their day-to-day behavior; the competence of their administration and the authority and legitimacy which their regime displays; and finally, in a fundamental constitutional sense, their ability to respond to change, to assimilate other minor groups into the mainstream of political life, to maintain their autonomy vis-à-vis other groups or states, and to respect and nurture the complex elements of their sovereign domain.

The socio-economic dimension encompasses the tangible process of fulfilling the functions of the sovereign organization (not necessarily a nation-state), and is particularly concerned with the allocation of goods and services among the different constituent groups. Order, protection, and conservation being three of the broad functions of the traditional nation-state, these may be further defined:

— Order would reflect the degree to which control is maintained over all non-coercive sources of power; the provision of the institutional framework within which the state moves to attain its goals; the maintenance of a degree of stability conducive to the social process; and the provision and regulation of those services essential to the integrity and prosperity of the sovereign organization.

— Protection must encompass both the provision of a secure environment for society, and the nature and potential of the coercive forces permitting the enforcement of national standards; justice in the administration of sanctions and the allocation of resources; and the consequent welfare of the population and, by extension, the parent organization.

— Conservation, an aspect of responsibility of increasing interest to scholars and the public alike, reflects the role of the sovereign organization in developing itself and its elements; health, education, equal opportunity, ecological sensitivity; technical sensitivity.

The ideo-cultural dimension is different from the socio-economic; whereas the socio-economic dimension encompasses the physical and institutional mechanisms by which the sovereign organization moves to achieve its goals, this dimension concerns itself with the spiritual means of coordinating the population, establishing the sense of community and inter-relatedness necessary to move forward.

— This is a subtle and difficult area of interest. The faith of the population in the myths and institutions through which organizations manifest themselves will be difficult to gauge. The degree of obedience which can be extracted will be somewhat more easily calculated.

— The promulgation of, and popular adherence to, role specializations (and, by extension, class and occupational stratification) will be crucial to the stability of the political-legal and socio-economic systems.

— This dimension is traditionally neglected because of its difficulty, yet it is the normative behavior patterns engendered by ideological belief and cultural tradition that will do much to determine the perception of personal injustice on the part of elements of the population, and hence the degree of violence to which some might aspire in seeking redress.

The techno-demographic dimension includes both technology and demography; both are variable sources of power for any sovereign organization.

— The degree of technological sophistication, and the pervasiveness of the technologies—to name three—of communication, education, and employment, will suggest ideas about the capacity of the incumbent regime and the obstacles and advantages of any who might become insurgents.

— The national infrastructure, including national, state, and local intelligence-gathering and processing capabilities, will affect the nature of any revolutionary process.

— Demographic considerations include both the capacity of the population as enhanced by available technologies, and the distribution of the population geographically, socially, and intellectually.

— The urban-rural balance, the dependency ratio (percent supported by the remainder of the population), and the degree to which the majority of the population is or is not literate (both symbolic-literate and technique-literate) will be especially important.

The natural-geographic dimension includes both the somewhat unpredictable aspects of natural disaster, and the relatively static nature of geographic resources. Energy resources and mineral wealth, and their increase or decline in value as substitutes are identified, determine the ability of the sovereign organization to care for its people. The ability of the land to support diverse primary products, the possession of a sea coast and major waterways or central valleys facilitating access to all parts of the nation, the temperature, the topography of the terrain, and the continental position of the territory in relation to benign or hostile neighbors will all be of significance in estimating the likelihood and outcome of revolutionary developments in the other dimensions.

Defining Revolution

Without belaboring the relatively limited definitions of others, or the rationale for reaching these specific definitions, some original definitions are provided below.

Revolution

1. The type of change must be predominantly political, legal, social, economic, or ideological.

2. The extent of the change must be severe.

3. The scope of the change must be pervasive, encompassing at least two of the major types of change.

4. The pattern of change must become persistent eventually, although it may be random or sporadic for some time.

5. The rate of change must be fast if not rapid.

Revolutionary Change

Change in any dimension which is severe and rapid.

Revolutionary Conflict

One in which revolutionary change characterizes the confrontation.

Revolutionary Movement

One whose members are engaged in a revolutionary conflict against the prevailing regime.

Great Revolution

A condition in which revolutionary change is occurring simultaneously in the political-legal, socio-economic, and ideo-cultural dimensions.

These definitions, in combination with an understanding of change and the enumeration of the dimensions to be considered, satisfy the first requirement for a theory of revolution, that of delimitation.

A Revolutionary Typology

Classification of different types of revolution follows logically.

Major Change

Political Conspiracy

Legal Abrogation

Social Uprising

Economic Insurrection

Ideological Antistrophe

Cultural Renaissance

Minor Change

Technological Strike

Demographic Rebellion

Natural Catastrophe

Geographic Conquest

Military Coup

Figure 3. A Revolutionary Typology

A political conspiracy is an initially covert movement with limited membership which seeks to subvert those in power and assume their positions of authority.

A legal abrogation is the annulment or revocation of the official policies of the sovereign organization, of the constitution which pretends to legitimize the regime, through organizations and processes already recognized by society.

A social uprising is the popular rejection of a government, its policies, or the conditions which it seeks to impose, by means of an unorganized demonstration of opposition.

An economic insurrection is an unorganized or at least fragmented revolt against the economic stratification of the population, and the allocation of resources which this implies.

An ideological antistrophe is the peaceful promulgation and general acceptance of a coherent ideological alternative to the existing philosophies of state.

A cultural renaissance is an organized movement to assess and revitalize cultural traditions and elements to better reflect or indirectly influence the philosophy and practice of the sovereign organization.

A technological strike is a limited expression of particular grievances amenable to compromise and of a predominantly technical nature.

A demographic rebellion is a generally ego-centric, conscious or unconscious, resistance to authority and the mores which the authority seeks to impose on the individual.

A natural catastrophe is the alteration or transformation of the environment within which the society and its organizations operations.

A geographic conquest defines the relatively complete assumption of control of a particular territory and its resources by force of arms. It could also pertain to a radical change in the manner of exploitation of a territory by its existing owners.

A military coup is an organized movement to replace the existing government by peremptorily (implicitly forcefully) replacing person associated with the movement in positions of authority.

Change in any dimension, and combination of dimensions in change, can occur without necessarily being revolutionary. As outlined in the section on change, the change must be severe and rapid, and ultimately sustained, for a revolution to occur. The above topology provides half the framework within which to examine the preconditions of revolution. The second half of the framework accentuates the role of people in bringing about change.

WHY: People and Their Perspective

The following model of psychological development is drawn entirely from the seminal work of Charles Hampden Turner. Most authors treating the topic of revolution fail to highlight the role of the individual, dealing instead with people from one of two extreme positions: either as social units, to be spoken of as :leaders” or “followers,” or members of a mass responding to inevitable social forces; or they are regarded as simple containers for the psychological chaos induced by relative deprivation and its associated theories of motivation. Very few authors have reflected an awareness in their works of the depth of human feeling as a basis for rebellion, insurrection, insurgency, and other forms of revolution. Two who did, David C. Schwartz and George Petter, merit quotation:

“To him who makes it, a revolution becomes a reason for being, an engagement with the cosmic, a transmutation of the self with history; indeed, a transmutation of the self. Revolutions occur when the core of that self—the self-defining characteristics of a people—are threatened or demeaned.”

“A (revolutionary) myth is at its center a picture of man. That is the simple reason why the older myths generally are woven as a story around an individual protagonist. It is perhaps the basic weakness of modern myths that they possess no clear picture of human nature.”

A superb model of the human aspect is provided by Charles Hampden-Turner, who identifies nine specific elements of psycho-social development which, when related to the dimensions of change, will yield a matrix for observing and evaluating the preconditions of revolution.

Perception

Identity

Competence

Investment

Suspension

Extroversion

Transcendence

Synergy

Complexity

Figure 4. Aspects of Human Development

Perception is the ability to see discrepancies between what is and what might be; radical man must not only bear his vision of what is not being provided his fellow man, but his premonitions of what is likely to befall his peers as a consequence of existing practices. The ability to gather and appreciate undistorted information emerges here. Perspective, the ability to aggregate the experiences of others, emerges.

Identity pertains to the ability of the individual to recognized both his own limitation and the limitations inherent in his environment; this is essential to balanced growth, allowing adjustment to external opportunities and a strategic enhancement of personal capabilities. A sensitivity to external conditions is manifested.

Competence combines perception and identity into a personal ability to establish and achieve goals, a personal efficiency.

Investment requires the authentic and intense dedication of one’s own capacities to a common good.

Suspension refers to the ability to risk one’s self and one’s beliefs in open confrontation with others, permitting the recognition of unfiltered and unadulterated information; this must be complemented by adaptability.

Extroversion, a complementary trait to investment and suspension, is the active effort by an individual to inter-act with others, integrating their perspectives and goals with one’s own. Participation is critical.

Transcendence is external, reflecting one’s success at making a contribution to others as demonstrated in their adoption of one’s perspectives or objectives. Equality is a foundation for the interaction that leads to transcendence.

Synergy comes about when extroversion on the part of many radical beings adjusting to one another not only effects transcendence, but leads to “larger than life” shift enhancing the abilities and perspectives to the group as a whole. Synergy is the actualization of community.

Complexity is the reconciliation of dichotomies discovered in facing others and the environment, leading to the integration of the individual and those he confronts into a more complex pattern of thought and existence. The balance represented by this trait is—in a word—sanity.

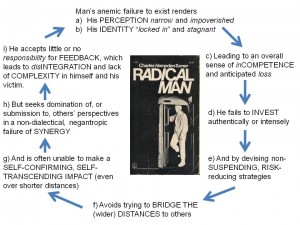

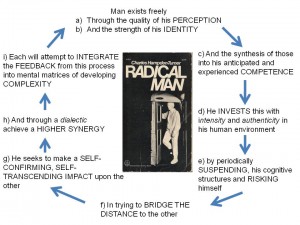

Below are two illustrations included in the thesis but not included in the MCU paper.

Done wrong:

Done right:

Preconditions of Revolution

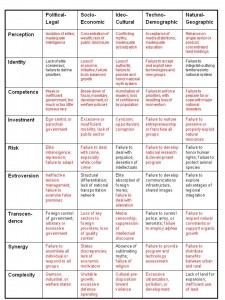

Having set the stage for consideration of the pre-conditions of revolution, the graphic which follows presents a consolidated matrix with numerous pre-conditions of revolution. Approximately a third of these were readily identified by other authors; the remainder were original extrapolations developed with the aid of this new analytic model. For this online rendition, I am using the USA version, i.e. my judgment of what conditions exist in the USA today is shown with text in red.

A detailed discussion of each of the pre-conditions included in the framework will not be provided here (see the original thesis). Each can be associated with specific elements of information which can be collected and evaluated, i.e. each pre-condition can be “operationalized to permit systematic research across organizational and geographic boundaries, and thus the comparison and contrast of different political-legal, socio-economic, ideo-cultural, and techno-demographic regimes.

In each case, where a precondition exists, it can be said that an aspect of human development is being faulted—the responsible individual or group is guilty of a lack of perspective, sensitivity, efficiency, dedication, adaptability, participation, equality, community, or—the ultimate failing—sanity.

Preconditions can be ameliorated or contained by countervailing forces; Eckstein identified four: facilities maintained by the incumbents, effective repression, adjustive concessions, and diversionary mechanisms.

Preconditions may also exist for lengthy periods without necessarily leading to revolution. Concentration camps are one example of sub-human circumstances which can be countenanced without revolt. For the revolutionary process to begin, some kind of catalytic event appears to be required. For the process to be sustained, the ingredients of the formula must be present in proportion and strength.

WHEN: Precipitants of Revolution

The essential distinction between precipitants and preconditions of revolution is one of spontaneity and dramatic force. Whereas preconditions develop over time, and are generally mitigated by the whole range of social issues and circumstances, precipitants are usually limited to easily visible and understood occurrence taking place over a short period of time, often only a few minutes. [In Arab Spring terms, the Tunisian fruit seller self-immolating—although one US veteran has burned himself to death in front of a New Hampshire courthouse, this was hushed up—a soccer mom on the steps of City Hall in New York City cannot be hushed up.]

The importance of the precipitating event as a catalyst of revolution lies in its unmitigated demonstration of the total incompetence, irresponsibility, or corruption of the authorities.

The precipitating event, which must be founded on the existence of the appropriate preconditions if it is to be successful, performs two functions:

— It illustrates to those who are radicalized the failure of the sovereign organization, and to those who are not politicized the possibility that something is terribly wrong (opening their minds to alternative ideological and organizational schemes); and

— It suggests to all who care to consider the matter the possibility that a revolutionary movement may be successful.

Both preconditions and precipitants serve to reduce the legitimacy and authority of the regime in the eyes of the people. Preconditions, however, are generally limited to evidence of the regime’s declining capability to govern effectively in the positive sense (fulfilling its responsibilities to “deliver the goods” and provide services of common concern), while leaving largely intact the public’s perception of its ability to employ repressive force.

Precipitants, by contrast, may not actually reduce the repressive capabilities available for employment, but they may either hamper the ability of the regime to bring those forces to bear, or so motivate the public that fear of repression becomes incidental to the point of overcoming the repressive forces en masse. [In Arab Spring terms, the “wall of fear” came down.]

One noted authority on precipitants, M. Rejai, has identified four categories of catalytic happenings; historical accidents, risks, subversive or repressive operations, and nationally significant events.

— Historical accidents might include such things as the failure of a nuclear power plant, demonstrating the deception practiced by the government in its propaganda on the safety of such facilities. It merits comment that the importance of historical accidents seems to increase in terms of revolutionary potential in relations to the increased complexity and interdependence of societies. As the technological complexity of a society increases, both the possible consequences of a relatively small failure (e.g. a computer virus in an aircraft control system), and the ability of the population to become rapidly informed, and incensed, increase.

— Risks are divided by Rejai into ideologically-motivated risks, unappreciated risk incident to rebellion, and imposed risks. Ideologically-motivated risks might be founded on a messianic belief in the inevitability of success, and allow a crippling general strike to be mounted and maintained. Individual rebellion, perhaps taking the form of substance abuse, could in turn lead to the taking of risks whose magnitude is not understood by the individual. Imposed risk, such as conscription and attendant battlefield losses, could lead to a catalytic rejection of the regime.

— Subversive or repressive operations are traditionally recognized as likely to lead to increased revolutionary activity. Both terrorism by insurgents, and terrorism by the regime, are likely to polarize a society and establish an increased probability of revolution.

— Nationally-significant events encompass military defeats and economic crises, natural disasters, political scandals, the impact of other revolutions, and change and reform instigated by the government with unanticipated consequences.

WHO and HOW: The Revolutionary Process

For a revolution to be sustained, certain ingredients must be present to sufficient degree, and a relatively predictable process must run its course.

Revolutionary leaders must be available. They will tend to be thirty to forty years old, of middle-class origin, professionals, familiar with urban settings, and members of the intellectual class, or at least relatively well educated. Two noted authors, Carl Leiden and Karl Schmitt, have stated:

“…the lower classes are generally underrepresented because they are deficient in the skills and experience for leadership and political manipulation, and the upper classes because they tend to be satisfied elements that resist basis changes that a mass uprising would support.”

Leiden and Schmitt go on to suggest that rebel leaders appear to be characterized by qualities of will, courage, and the ability to concentrate on essentials, while often displaying highly emotional natures, and unshakable conviction (a good basis for iron discipline).

Such authors as Eric Hoffer and Brian Crozier have also focused on the common element of frustration among revels—unappreciated imaginativeness, under-utilized talent, and frustrated idealism are identified as prominent characteristics of most rebel leaders.

Leiden and Schmitt, drawing on the work by Hoffer and Rex Hopper, distinguish between agitators, reformers, and activists, the latter in turn divided between statesmen and administrators.

— Agitators, noted for their fanaticism, and reformers, akin to prophets, work in tandem to undermine the regime. The agitator uses violence and organization, the reformer ideology and dialogue.

— Statesmen and administrators emerge after the agitators and reformers have set the stage. Statesmen formulate the social policies promised the followers, while evaluating the social forces driving the revolution; administrators are technicians able to manipulate the old and new institutional mechanisms.

Leaders need followers. Membership in revolutionary organizations, as explored by Kurt Lang and E. Gladys, will usually include the socially inferior classes who are deprived of their “just share” of social goods; preadolescents and adolescents whose developing adult interests go unrecognized in conventional groups; minority groups and other “marginals” who are not fully accepted; and the rootless intelligencia frustrated in the legitimate employment of their “creative” aspirations.

Organization can make the difference between an uprising or insurrection of passing duration, and a sustained revolution. Among the pre-requisites identified by Schwartz which must be met if individuals are to become dedicated to a common organization:

1. There must be a perception of common interests, of similarity.

2. There must be a perception of the necessity for group action.

3. There must be agreement on the efficacy of the particular projected organization.

4. There must be at least some compatibility or congruence in personal style among the projected members.

5. There must be constructed commonly acceptable symbols (or common foci, backgrounds, and beliefs).

The association, as discussed by Lang and Gladys, will:

1. Offer the psychological support requisite for permanence by which doctrines, cultish fads, and other practices are sustained;

2. Nurture ideologies and doctrines, in the shelter of the group, to the point at which they can be presented openly; and

3. Through agitation and proselytizing the message, ultimately carry the message to a larger following which constitutes the social movement.

Ideology will be a critical ingredient in bonding the membership together and maintaining momentum. Its success in winning and holding the allegiance of members will depend on its internal consistency and coherence, its claim to traditional foundations, its postulation of a glorious but credible future, its depth and scope in providing a framework for understanding or at least explaining the situation, and perhaps most importantly, suggesting how equilibrium might be restored. Any examination of potential revolution conditions in any dimension cannot be complete without some consideration of these elements of process.

Students of revolution disagree about whether or not a revolutionary leader can have a strategy. Those that feel strategy per se is unachievable in a revolutionary context focus on the power of the revolutionary forces, suggesting that leaders may at best select the means of revolutionary action, tactics and timing and targets, but that ultimately the momentum of the masses will take on a life of its own. Others, while acknowledging the unpredictability of revolutionary forces, point out that certain fundamental can be addressed and integrated into an over-all revolutionary strategy. Among these fundamentals would be:

— Development of an international legal position to facilitate collection of assistance and isolate the established regime. Control of some territory is one of the traditional preconditions for recognition. At a minimum, recognition or tacit acceptance by at least one country is the region, ideally a country contiguous to the home country, is needed to provide for sanctuaries and staging areas.

— Promulgation of a strategic vision, whether ideological or pragmatic, is essential to nurture cross-cutting alliances, begin the process of neutralizing the army, and of assimilating, negotiating with, or discrediting competing revolutionary groups.

— Finally a strategy for resource management is helpful, one which guides the mobilization of membership and the accumulation of resources. The establishment of a reliable intelligence network, conscription of skilled manpower, hoarding of arms and supplies, the preparation of strong-holds and other elements of the revolutionary infrastructure will be important as a basis for transitioning from revolution to incumbency.

The revolutionary process has been characterized by Rex Hopper as having four stages: the preliminary stage of mass (individual) excitement, the popular stage of crowd (collective) excitement and unrest, the formal stage of issue formulation and the creation of publics, and the institutional stage in which the revolutionary process is legalized and social organizations created or controlled by the revolutionaries. A good summary of these processes, of the stages of revolution, is provided by Lawrence Stone:

— “The first is characterized by indiscriminate, uncoordinated mass unrest and dissatisfaction, the result of dim recognition that traditional values no longer satisfy current aspirations.”

— “The next stage sees this vague unease beginning to coalesce into organized opposition with defined goals, an important characteristic being a shift of allegiance by the intellectual from the incumbents to the dissidents, the advancement of an ‘evil men’ theory, and its abandonment in favor of an ‘evil institutions’ theory. At this stage there emerge two types of leaders: the prophet, who sketches the shape of the new utopia upon which men’s hopes can focus, and the reformer, working methodically toward specific goals.

— “The third, the formal stage, sees the beginning of the revolution proper. Motives and objectives are built up, a statesman leader emerges. Then conflicts become acute, and radicals take over from the moderates.

— “The fourth and last stage sees the legalization of the revolution. It is a product of psychological exhaustion as the reforming drive burns itself out, moral enthusiasm wanes, and economic distress increases. The administrators take over, strong central government is established, and society is constructed on lines that embody substantial elements of the old system. The result falls far short of the utopian aspirations of the early leaders, but it succeeds in meshing aspirations with values by partly modifying both, and so allows the reconstruction of a firm social order.”

Stage One: Individual Excitement

Perception of disequilibrium

Identity established with others

Stage Two: Collective Unrest

Competence in organizing

Investment (dedication) to the group

Stage Three: Formal Transition

Risk adoption becomes common

Extroversion becomes the norm

Stage Four: Legalization

Transcendence through integration

Synergy through success

Figure 6. Aspects of Personality and the Revolutionary Process

Conclusion

This article has provided a summary look at the elements of theory pertaining to revolution, and has outlined a framework for observing and evaluating the preconditions of revolution.

Emphasis has been placed on defining the nature of change, distinguishing the different dimensions within which revolution can occur, and appreciating the signal importance of aspects of human development in the revolutionary process.

A topology of revolution, listing and defining eleven different manifestations of revolutionary change has been provided.

One hundred and three specific and distinct preconditions of revolution have been listed in the context of the framework created by combining the dimensions of change with the aspects of human development.

Revolution is not simple; understanding revolution is difficult. Without at least an elementary grasp of a theory of revolution, and an appreciation for the range of conditions and the role of human character in sparking and sustaining revolution, understanding would be impossible.

When all is said and done, two precepts stand out:

— The first, from Aristotle, “moderation in all things.” Extremism breeds reaction and revolt. The concentration of wealth, or privilege, any sustained disparity between the aspirations of the many and the condition of the few, will ultimately cause some to seek redress.

— The second, from the theory of cybernetics: adaptation to changed externalities distinguishes evolution. It is the failure of the governing elite to recognize changed externalities, invest in adaptation, extend themselves to others, and transcend their conditions, which sparks countervailing revolutionary movements.

At the root of revolution, then, is the human condition and the human mind. Will and Ariel Durant, in The Lessons of History, conclude a lifetime of reflection by commenting:

“We have defined civilization as ‘social order promoting creation.’ It is political order secured through custom, morals, and law, and economic order secured through a continuity of production and exchange; it is cultural creation through freedom and facilities for the origination, expression, testing, and fruition of ideas, letters, manners, and arts. It is an intricate and precarious web of human relationships, laboriously built and readily destroyed.

“The only real revolution is in the enlightenment of the mind and the improvement of character, the only real emancipation is individual, and the only real revolutionists are philosophers and saints.”