What Was Novel About Social Media Use During Hurricane Sandy?

We saw the usual spikes in Twitter activity and the typical (reactive) launch of crowdsourced crisis maps. We also saw map mashups combining user-generated content with scientific weather data. Facebook was once again used to inform our social networks: “We are ok” became the most common status update on the site. In addition, thousands of pictures where shared on Instagram (600/minute), documenting both the impending danger & resulting impact of Hurricane Sandy. But was there anything really novel about the use of social media during this latest disaster?

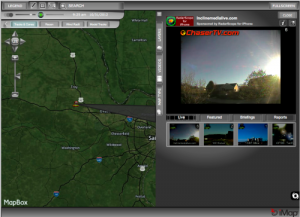

I’m asking not because I claim to know the answer but because I’m genuinely interested and curious. One possible “novelty” that caught my eye was this FrankenFlow experiment to “algorithmically curate” pictures shared on social media. Perhaps another “novelty” was the embedding of webcams within a number of crisis maps, such as those below launched by #HurricaneHacker and Team Rubicon respectively.

Another “novelty” that struck me was how much focus there was on debunking false information being circulated during the hurricane—particularly images. The speed of this debunking was also striking. As regular iRevolution readers will know, “information forensics” is a major interest of mine.

This Tumblr post was one of the first to emerge in response to the fake pictures (30+) of the hurricane swirling around social media whirlwind. Snopes.com also got in on the action with this post. Within hours, The Atlantic Wire followed with this piece entitled “Think Before You Retweet: How to Spot a Fake Storm Photo.” Shortly after, Alexis Madrigal from The Atlantic published this piece on “Sorting the Real Sandy Photos from the Fakes.”

These rapid rumor bashing efforts led BuzzFeed’s John Herman to claim that Twitter acted as a truth machine: “Twitter’s capacity to spread false information is more than cancelled out by its savage self-correction.” This is not the first time that journalists or researchers have highlighted Twitter’s tendency for self-correction. This peer-reviewed, data-driven study of disaster tweets generated during the 2010 Chile Earthquake reports the same finding.

What other novelties did you come across? Are there other interesting, original and creative uses of social media that ought to be documented for future disaster response efforts? I’d love to hear from you via the comments section below. Thanks!