Want to understand why the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have broken the bank?

Then I suggest you carefully read the attached report in the current issue of Harpers, written by my very good friend Andrew Cockburn. The subject of this brilliant and very important report is the Pentagon's battle against land mines in Iraq and Afghanistan. Land mines are one of the oldest and most effective forms of warfare [see my essay, Why Mines Warfare is Good for Protracted War, in Counterpunch, 12 January 2011]. They are weapons of choice for the weak, guerrillas in particular, something we certainly should have learned from Vietnam.

Nevertheless, the high tech Pentagon was caught flatfooted by land mines and booby traps in Afghanistan in Iraq. The surprise was so complete that “planners” found it necessary to spend $60 billion since 2001 to counter what they euphemistically call Improvised Explosive Devices, as if booby traps constructed by guerrillas were a new and unexpected thing. Notwithstanding this huge expenditure on technology, a cornucopia for defense contractors much greater in fact than the Manhattan Project, even if one removes the effects of inflation, Cockburn lays out a splendid micro history of what really worked — guts, brains, and most importantly, what the Germans used to call fingerspitzengefühl*; and what has not worked — high-cost, high-tech boondoggles produced by contractors, employing gobs of retired military to help them cash in on the golden cornucopia unleashed by the dogs of war.

Although Cockburn does not use the term, fingerspitzengefühl, his telling of the legendary story of how a wily Marine sergeant got inside the heads of Iraqi and especially the devilishly clever Afghan booby trappers is a stunning example of fingerspitzengefühl in action, illustrating Colonel Boyd's dictum: machines don't fight wars, people do and they use their minds. Contrast the intuitive mind of MSgt Chavez as he sweats in the trenches, putting his life at risk above and beyond the call to duty, to the asinine** brain-dead boast about the performance of Gorgon Stare, a new high cost surveillance program, made Major General James O. Poss, “there will be no way for the adversary to know what we're looking at, and we can see everything.” Poss, the Air Force’s assistant deputy chief of staff for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, ought to know there has been an intelligence problem in Afghanistan, yet he made this boast to a credulous media in Hall of Mirrors that is Versailles on the Potomac in January of 2011. Ironically, as Cockburn explains below, Poss was describing the performance of a new high-tech surveillance program, Gorgon Stare. However, there was fly sitting on Poss's intellectual dungheaap: the chief of testing for the Air Force's 53rd Test Wing wrote in late December 2010 that Gorgon Stare had been declared “not operationally effective and not operationally suitable.”

Now, after reading Cockburn's report, ask yourself a question: Who has a better understanding of the moral and mental nature of war? The unwashed grunt sweating in trenches or the polished courtier in Versailles flacking for higher budgets. Maybe it is time to Occupy the Pentagon as well as Wall Street.

* literally, the fingertip touch, a term used to describe one's intuitive feel and connection to one's environment.

** I use the modifier asinine advisedly and explained in an earlier blaster, If You Can See Everything, Can You Know Anything?

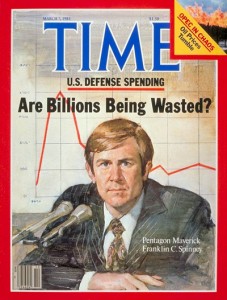

Chuck Spinney

Barcelona, Catalunya

Search and Destroy

The Pentagon’s losing battle against IEDs

>By Andrew Cockburn, Harpers, November 11, pp. 71-77

Andrew Cockburn writes frequently on defense and national affairs, and is the author, most recently, of Rumsfeld: His Rise, Fall, and Catastrophic Legacy.

EXTRACT:

Thinking of the ingenious solutions emanating from the $60-billion counter-IED effort, I asked Chavez what technology he had personally found most useful. “Technology will fail you when you need it the most,” he replied. “You have to keep it simple. I carried a stick with a hundred feet of parachute cord wrapped around it. That was my most useful tool.”

Along with the cord, which he used to pull bombs apart, he carried wire cutters, a small metal detector, his rifle and pistol, and a radio. Chavez also made use of three kinds of explosives: C4 for “cutting” (piercing the outer layer of artillery shell casings), TNT for “pushing” (moving dirt off a bomb), and thermite for burning off brush. He had little use for the robots developed to deal with bombs remotely. His battleground, he explained, lay among close-packed compounds, and the passageways between the buildings were generally too narrow for any robot. Nor did he think much of the bulky “bomb suit” worn by the hero in the movie The Hurt Locker. “In one-hundred-tendegree heat?” he asked.

Phi Beta Iota: To this we would add the shameful fact contributed by MajGen Bob Scales, USA (Ret) – the infantry (4% of the force) takes 80% of the casualties, and despite the fraud, waste, and abuse that Cockburn describes above, receives less than 1% of the total Pentagon budget.

See Also:

Angst from Afghanistan: A Grunt’s Statement

Chuck Spinney: Economic Costs of Warmongering

DefDog: Laser to Detect Improvised Explosive Devices (IED)

New Army Chief of Staff: Out of Touch? NEW: Blistering Bullshit Flag Waved from Afghanistan

Reference: 27 Sep MajGen Robert Scales, USA (Ret), PhD