Defense Science Board Off Point on Open Source Intelligence Reform

Gregory Kulacki

Union of Concerned Scientists, 28 January 2013

About the author: Gregory has lived and worked in China for the better part of the last twenty-five years facilitating exchanges between academic, governmental, and professional organizations in both countries. Since joining the Union of Concerned Scientists in 2002, he has focused on promoting and conducting dialog between Chinese and American experts on nuclear arms control and space security. His areas of expertise are Chinese foreign and security policy, Chinese space program, international arms control, cross-cultural communication. He received his Ph.D. in Political Theory from the University of Maryland, College Park in 1994.

Last week the Defense Science Board (DSB) released a report calling for reforms in the way the U.S. government monitors the development and proliferation of nuclear weapons programs around the world. The Board found there are “gaps” in the U.S. intelligence community’s “global nuclear monitoring” capabilities. It argued that closing these gaps “should be a national priority.” The report recommended adopting “new tools for monitoring,” including looking at “open and commercial sources” with “big data analysis.”

Searching through vast amounts of openly published information with computers is not a new idea. Some of the U.S. intelligence community’s tried and true sources and methods were depicted and subtly critiqued in the opening scenes of Three Days of the Condor: a 1975 spy thriller. Robert Redford plays a CIA analyst who works for a front called the American Literary Historical Society. As Redford explains later in the film, “We read everything that’s published in the world. I look for leaks. I look for new ideas. We read adventures and novels and journals. Who would invent a job like that?” In a classic case of what is old is new, the DSB, it seems, wants to reinvent it.

In the opening scene of the movie a young Chinese-American analyst reminds her colleagues of the computer’s limitations. Then Redford questions her about the different meanings of the Chinese character 天. She explains it means “heaven.” Redford asks, “That’s it, nothing else?” She responds, “Well it can mean, ‘the best’, ‘tops’ sometimes, why?” A few moments later Redford presses, “Are you sure about this ideogram?” “Look at this face,” she asks, “Could I be wrong about an ideogram?” With a smile and lingering doubt Redford notes, “It’s a great face, but it has never been to China.”

That is a very important point, and one completely lost, it seems, on the Defense Science Board.

In its report, the Board also turned to China for an example of sources and methods. It cited a discredited study of China’s nuclear forces, funded by the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA), as a “proof of concept” for the Condor-like, old-as-new reform it suggests in its report. The “crowd-sourced” study of China’s nuclear arsenal was conducted by undergraduate students at Georgetown University, who assembled a large collection of video, images and text related to China’s nuclear arsenal using keyword searches on the Internet. The DSB admitted there are questions about “the veracity” of the DTRA-funded Georgetown study. But it mistakenly sees data collection as the problem. The report criticized the “untrained” students for selecting “a semi-fictionalized Chinese TV series” as one of their intelligence sources, as if that were why the study was discredited.

The Board missed the point. The data this “crowd” of “untrained” students collected was not the problem. The problem was what their teacher, a retired U.S. intelligence professional, tried to do with it.

All data can be interesting and useful, which is why the NSA, Google and Facebook collect so much of it. But data is only useful if you know what to do with it. A work of fiction about China’s nuclear arsenal could provide a treasure trove of information in the hands of an analyst who understands the language, the culture and the content. The “gaps” in the U.S. intelligence community’s ability to carefully monitor China’s nuclear program are not in its capability to collect data, but in its ability to understand what it collects. UCS published more than a few studies documenting U.S. intelligence community failures in translating and interpreting open source Chinese language publications containing information about China’s nuclear weapons and space programs.

In some cases, this problem is partly due to a lack of careful scholarship, which requires an awareness of the limitations of the available knowledge, an understanding of how far one can go in drawing conclusions from it, and a willingness to ask tough questions about those conclusions to see how well they hold up to scrutiny.

But these gaps and failures are also the product of an institutionalized deficiency in the way the U.S. government recruits and trains intelligence analysts. In order to acquire the language and cultural skills needed to perform meaningful analysis and interpretation of Chinese cultural products, from news reports to television shows, the prospective analyst must spend a considerable amount of time in the target culture. That allows one to understand, for example, the nature and credibility of different newspapers, institutions, etc. But the U.S. intelligence community, for understandable reasons, does not want to hire people who spent too much time in China, who know too many Chinese people, or who seem otherwise attached to the place. Such people are considered a security risk, or biased. I referred to this deficiency in an earlier post on ICD 630: a recent directive from President Obama’s Director of National Intelligence aimed at closing some of the same intelligence gaps identified by the DSB.

Rather than “crowd sourcing” data collection to feed NSA-like computer programs, the U.S. intelligence community should look for ways to leverage the considerable language and cultural expertise that resides outside of government to help it monitor open source data it lacks the skills to use properly.

A cheap, quick and effective place to start would be restoring public access to the database of foreign news reports managed by the CIA’s Open Source Center. Restoring public access would allow non-government affiliated researchers with robust language and cultural skills to monitor the database for mistakes in translation. They could also provide feedback to the CIA on the nature and quality of the sources it is selecting for translation. This type of “crowd-sourcing” could improve the quality of the information the CIA makes available to government consumers of this often-used source of open intelligence data. Unfortunately, the Obama administration seems to be moving in the opposite direction, strengthening prohibitions on access to the database, which I could use without restrictions when I was an undergraduate student back in 1975.

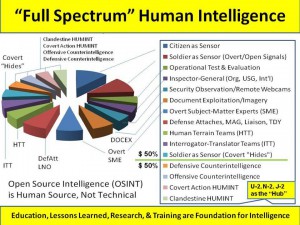

Phi Beta Iota: Above is a marvelous critique of the DSB's lack of understanding of real Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) which is 80% Human Intelligence (HUMINT) and not the technical intelligence from online surfing that lazy ignorant bureaucrats have made it. It is also an excelent critique of the idiocy of the US IC in how it recruits children that do not speak the language and have never visited the country because our moronic security system cannot handle nuances or complicated narratives. What he misses is the rest of it: the CIA clandestine service forbidding the Open Source Center (OSC) from networking with overt human sources; the CIA's security service preventing analysts from speaking with foreigners and even with most US citizens who lack clearances, unless under controlled circumstances; the complete incompetence of most Embassy Country Teams, where the diplomats are out-numbered, too few, and have no money for entertaining; and the absolute refusal of the US Government to a) share information across agency lines not just within the IC but between the IC and its consumer-clients; and b) do multinational, multiagency, multidisciplinary, multidomain information-sharing and sense-making (M4IS2). The IC, is, in one word, incompetent. Bloomberg has it right — the NSA is offering a losing argument but the fact is that NSA's mass surveillance is not our worst problem, only our most expensive waste. CIA lost its analytic integrity in the 1950's when the clandestine tail started wagging the all-source analytic dog. It collapsed further when George Tenet gave up his personal integrity first working with the FBI and Keith Alexander to raid and then dismantle ABLE DANGER on 9/11 advance warning, and then supporting Dick Cheney's 935 lies on Iraq while also working. It finally earned eternal damnation with its drone assassination program setting a new low in operational effectiveness (never mind the lies told to the White House and Congress, a 2% success ratio and a 98% atrocity ratio is beyond the pale). The rest of the IC is a disgrace as well. The NGA is an old folks home for failed Army Colonels, the NRO is being outdone by start-ups with micro-satellites, and DIA still has not figured out the difference between strategic, operational, tactical, and technical analytics — nor do they have a clue on how to create a working global counterintelligence and clandestine human intelligence service that is both invisible and effective. All kidding aside, we are now at a point where the public interst would be best served by creating an Open Source Agency (OSA) and then dismantling 90% of the existing IC monstrocity, while funding 10% in new secret unilateral initatives and 10% in multinational secret initiatives.

See Especially:

2014 Rethinking National Intelligence — Seven False Premises Blocking Intelligence Reform

See Also:

2014 Intelligence Reform (Robert Steele)