When we worked on the Manhunting Project for SOCOM, the US Marshall's Service said that fugitive hunting was all about network analysis. The IC doesn't understand network analysis as the bean counters push for numbers….they focus on low hanging fruit and as a result there is always some guy out there ready to step up and take the foot soldier's place (not so much the upper echelons). Try to tell an IC drone that it is all about the network and you will get a deer in the headlight look….

Contributor: Louis DeAnda

Police forces have spent decades combating organised crime with well-practised techniques, but can the same tactics be the key to defeating insurgencies on the front line? Former police officer, federal marshal, and JIEDDO FOX team member Louis J. DeAnda tells Defence IQ how we need to take a holistic strategy to IED network attack…

Phi Beta Iota: Completely apart from the corruption at the top of both the Department of Justice and the Department of Defense, this is an extraordinary–a gifted–contribution to the literature. It is reproduced in full below the line to preserve it as a reference.

The Last War

I’ve spent a professional lifetime engaged in some form of network attack. Fifteen years of that career were spent along the southern U.S. border, or in Mexico itself, in constant investigative pursuit of various specialized cells of the Gulf Cartel or its progenitor, the Juan Garcia-Abrego Criminal Organization of the late 1980s. Investigative groups within the legacy U.S. Customs Service that I either worked in or later supervised pursued and prosecuted trafficking cells that specialized in land border smuggling, air smuggling, marine smuggling, concealed compartment construction, counter-surveillance, transshipment, distribution, precursor chemical diversion, and every form of money laundering.

We investigated kidnappings, robberies, burglaries, extortions, and homicides both in the U.S. and in Mexico, always attempting to link them to one cell or another through M.O., forensics, signature, financing, event chronology or – most preferably – a confession. We staked out their front businesses and the money exchange houses they used on both sides of the border. Our intelligence analysts collected and linked telephone numbers, addresses, people, vehicles, and businesses by the hundreds each month. Every major drug seizure at a domestic U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint was analyzed for its potential significance to ongoing investigations. We documented trucking companies, chemical companies, shipping companies, import/export businesses and brokers. Reams of notes listed associated criminal drivers, their cover loads, and cities of origin and destination. Our analysts correlated harvest seasons with marijuana seizures, and methamphetamine seizures with foreign bulk purchases of restricted precursor chemicals from the Far East. When we didn’t have enough probable cause to search for narcotics, we simply executed search warrants for other evidence that we did have sufficient probable cause to search for.

Seizures were often merciless. We took away boats, cars, houses, aircraft, condominiums and small businesses, as well as cash, jewelry, and bank accounts. Our IRS task force specialists conducted net worth analyses of our principal targets and compared their existing assets with their claimed incomes. When we found disparities we issued federal Grand Jury subpoenas to their nominees of convenience, forcing them to come to us and explain the large cash purchases. Fearing a federal perjury and income tax evasion charge, many often simply declined to make a statement and forfeited the assets. If so, we put their actions in the book and continued our investigations. When we didn’t have enough to target higher level principals, we targeted the “low-hanging fruit” that we could obtain criminal indictments against.

We knew the cartel attorneys that represented cartel cell members and we knew their tactics in the courtroom. We knew where the cell members’ kids went to school and who picked them up each day and at what time. There was a ton of physical and technical surveillance. When the cell members cheated on their wives, we documented it. We examined their criminal histories, their educational level, their work histories and their travel histories. If they took cream in their coffee, or preferred brunettes to redheads, we knew.

We couldn’t have done this without informants. Lots and lots of informants. We never missed an opportunity to vet someone who had access, placement, or some value-added knowledge, and it didn’t matter at what level because no matter how significant your top target was, he always had someone he either reported to or criminally competed with. Among my list were homeless people, medical doctors, disbarred attorneys, college professors, pilots, engine mechanics, farmers, warehousemen, and truck drivers. What they did for a living didn’t matter to me as much as what they knew or could position themselves to know.

We hit the cartel cells from every angle and we had really good public marketing campaigns called Zero Tolerance and Project D.A.R.E. that were on billboards, telephone booths, and shopping carts. Our slogans were plastered across truck stops, hardware stores, and even school lunchboxes. If you went to church on a Sunday morning, you’d find our counter-trafficking messages on pamphlets tucked into the missals. We were on the radio, the television, and at the movie theatres.

We hit the cartel cells from every angle and we had really good public marketing campaigns called Zero Tolerance and Project D.A.R.E. that were on billboards, telephone booths, and shopping carts. Our slogans were plastered across truck stops, hardware stores, and even school lunchboxes. If you went to church on a Sunday morning, you’d find our counter-trafficking messages on pamphlets tucked into the missals. We were on the radio, the television, and at the movie theatres.

Everywhere you turned there was a public service message to call our 1-800-BE-ALERT hotline to report suspicious activity that might be related to drug trafficking.

When we weren’t busy investigating, we were busy interdicting. We had land border tactical interdiction operations at known smuggling points along the international border between the ports of entry. U.S. Customs AWACs aircraft buzzed the skies almost every night. Marine interdiction units cruised out in the Gulf of Mexico and on major inland lakes with land borders. At the ports of entry, we used every single piece of technology at our disposal from the olfactory senses of drug hounds to the more expensive flexible fiber optic scopes, behavioral profiling, and massive X-ray scanning machines that could burn through an 18-wheeler in twenty seconds to detect any concealed cargo or smuggling compartments.

Hollywood may have you believe we always got our man, but in the real world drug smugglers occasionally slipped the net. Still, we caught enough of them to complete the complex prosecutions and dismantle entire cells. We applied technology there too. When the first copies of Analyst Notebook™ came out, we had them. We leveraged GIS, social network analysis, and human terrain analysis before they were popular.

When we prosecuted cartel cell members we used every statute we could prove. We prosecuted the principals under the RICO Act (Title 18 USC, Section 1962, et seq.) and the Continuing Criminal Enterprise statutes (Title 21 USC, Section 848) that brought penalties from 20 years to life imprisonment or even the federal death penalty under certain conditions. Mid-level participants got served with every substantive count we could bring and then we used conspiracy charges to legally combine criminal agreements and overt acts into individual crimes and individual crimes into cohesive criminal campaigns. We charged enhancements such as using or enticing juveniles to participate in crimes (Title 21 USC, Section 861) and weapons possession enhancements that doubled existing prison sentences. When we didn’t have enough to charge substantive violations of low-level cell members and criminal acquaintances, we charged them with Aiding & Abetting, Accessory after the Fact, and Misprision of Felony.

It didn’t end at the courthouse, either. After they were convicted and had spent some time in prison, we leveraged plea agreements and extended prison sentences to get them to talk. We kept track of convicts who were getting close to release and incorporated old crimes into new approaches because the mere thought of a new indictment to an inmate less than a year away from release was sometimes enough to get the crustiest convict to talk. Believe me when I say we honored all of our agreements.

It didn’t end at the courthouse, either. After they were convicted and had spent some time in prison, we leveraged plea agreements and extended prison sentences to get them to talk. We kept track of convicts who were getting close to release and incorporated old crimes into new approaches because the mere thought of a new indictment to an inmate less than a year away from release was sometimes enough to get the crustiest convict to talk. Believe me when I say we honored all of our agreements.

We did all of this cohesively and logically through a task force concept driven by the U.S. Department of Justice called the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force, better known by its acronym OCDETF (pronounced oh-see-deff). Major cases were constantly compared regionally through the El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC) a drug intelligence fusion center. They were compared nationally and internationally at quarterly conferences where special agents and analysts gathered to compare cases formally and informally. Trends within cartels were publicized and effective countermeasures broadcast to the group as a whole. The Assistant United States Attorneys who tried the cases in court highlighted successful prosecutions and even members of the criminal defense bar were routinely invited to provide their perspectives on prosecutorial strategies and how they defended their clients against them. We took the newest lessons learned and forwarded them to our national training academies for incorporation into the course curricula for new special agent trainees. The strategy was consummate, top-to-bottom.

The New War

Baghdad, early 2008.

My Law Enforcement Professional (LEP) partner, a retired career sergeant with the New York City Police Department’s elite Intelligence Division, emerges into the sun after several hours in an extended field interview with an alleged IED cell emplacer. He mimics pulling out non-existent hair from his bald head and his shouts dissipate into the dry air of the desert.

“My kingdom for a terrorist!”

Here in Iraq, the surge is in full effect and IEDs are detonating almost daily on Route Irish just over the perimeter wall from Forward Operating Base (FOB) Falcon.

Assigned to the HUMINT cell of JIEDDO’s Fox Team 1, I’ve begun noticing a strange pattern developing with each field interview of a terrorist, insurgent, or key criminal personality I conduct. I say “strange” simply because what I’m encountering is not what I had expected in terms of the collective psychology and personality of my suspects.

These guys were not the ideological True Believers that we had been prepared to encounter – far from it. These guys were Iraqi versions of the very same criminal personalities that my team partner and I had dealt with for our entire professional careers. They were Sopranos in kaftans.

They were not religious zealots by any means, but were instead criminal mercenaries…and not very smart ones, either. They had average educations for Iraqis, were highly opportunistic from an economic standpoint, identified socially from the micro to the macro level (family, neighbourhood, job/mosque, and tribe), and were typically networked 5-6 levels via on-the-job or mosque acquaintances, just as U.S. criminals were. Criminally, they were organized through classically cellular structures with most of the lowest level operators not actually members of the insurgent or terror organizations, but instead simply affiliated through a single insurgent who paid them on a fee-for-service basis to conduct surveillance, scout targets, guard weapons caches, and videotape attacks upon U.S. and coalition forces. Occasionally, the more trusted were paid to emplace IEDs (usually under some direct supervision from a bona fide card-carrying insurgent) but there was still money exchanging hands for the work and from an investigative perspective that was critical. You can exploit money.

Like any self-respecting gangster, the insurgent didn’t bomb in his own neighbourhood, but instead very deliberately travelled and remained within a comfort zone of familiarity to conduct insurgency operations, then returned home. The Shi’a affiliates had no problem bombing in Sunni districts and vice-versa, however. The degree of sophistication they displayed was reflected in their tradecraft (or lack thereof). The mosques and community centres were routinely key nodes for criminal communication and in some cases functioned as de facto insurgent C3I centres.

In precisely the same operational pattern as cartel cells of Latin America, these cells were functionally organized and highly opportunistic. An electronics store owned by an insurgent affiliate was perfect cover for the manufacture of IED detonators and cell phone components. A welding and mechanical repair shop doubled as a facility to construct concealed compartments in vehicles and trailers used to smuggle and transport explosives, intelligence documents, or even people past military checkpoints.

One of our largest insurgent munitions seizures came from a 2,000 gallon-sized, false water tank pulled by a pair of donkeys driven right down the middle of a major city road by a grizzled, white-bearded old Shiite man posing as a farmer. Gramps had with him brand new Iranian ordnance that included several hundred mortar rounds, 107mm rockets, sparkling new PKM machine guns still in their waxed packing paper lined with cosmoline, night vision equipment, many thousands of rounds of linked ammunition, and a smuggling method that should have given U.S. forces a major lead for border smuggling and tactical interdiction, just as a similar method would have in the War on Drugs. Rather than fingerprint the evidence, which we wanted to do and may have yielded some real surprises, the army EOD specialists hauled it all away for destruction…and the war continued. The smuggling method, the munitions themselves, and their condition, the old man, and the cart components were all important pieces that should have been analysed in detail and the results cohesively coordinated and disseminated as they would have been by the El Paso Intelligence Centre in the War on Drugs. But as the commanders made clear – we weren’t in Texas anymore.

So the major take-away from our fieldwork was that the overwhelming majority of the organized criminals we dealt with in Baghdad were no different from our old mob targets. There were no swarms of holy warriors martyring themselves at a moment’s notice to protect Islam from the Western infidel. Despite their superficial, politically correct veneer of religiosity, the overwhelming majority of insurgent/terrorists we dealt with were nothing more than opportunistic and organized criminal mercs.

The good news to report is that we have an approach that has already been proven for that criminal presentation…

Enterprise Theory of Investigation

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines a criminal enterprise as “a group of individuals with an identified hierarchy engaged in significant criminal activity.”1 It defines organized crime as “any group having some manner of formalized structure and whose primary objective is to obtain money through illegal activities.”2 These definitions are important to us in the GWOT because they provide the framework around which we may develop collaborative strategies for network attack.

For those who may not be familiar with it, Enterprise Theory of Investigation (ETI) is an investigative approach that perceives organized crime (OC) as a business, albeit a criminal business. Like any business, OC has a hierarchy of management and labour, an internal communications process, a profit motive, and rules for membership and conduct. It has administrative, logistical, operational, and support functions. OC is criminally opportunistic and although it may emphasize a particular venue of crime, such as drug trafficking, it routinely engages in a wide range of criminal activities that are generally consistent with the primary crime venue. Each of those activities provide venues for network attack by military/law enforcement.

We apply ETI when a criminal organization engages in a spectrum of criminal activities related to a central scheme. It permits us to leverage all OC substantive and ancillary criminal activities for their prosecutorial potential. Quite literally anything OC does in furtherance of any criminal initiative becomes part of the overarching criminal conspiracy and may be incorporated into the network attack.

Consider this. If I gave you the combined criminal venues of drug trafficking, violent extortion, money laundering, kidnapping, arson, weapons trafficking, homicide, and hostage taking and then asked to name the criminal organization to which I was referring, how many of you would have immediately guessed the Taliban of Pakistan? A more likely guess may have been the Italian or Russian Mafia, or perhaps the FARC of Colombia or even the cartels of Mexico. Any of those selections would have been correct, but then so would have Al Qaeda, Hezbollah, Jaish al-Mahdi, Lashkar-e-Taiba, the Lord’s Resistance Army, or any of the Somali pirate networks.

The fusion between organized crime and ideologically driven terror or insurgency is almost complete, which leads me to my next point of discussion.

Terrorist, Insurgent, or Organized Criminal Mercenary?

The Western militaries and the U.S. military in particular like it when its enemies fit a specific model that it has already prepared to fight. Sadly, that trend is rapidly vanishing and unless we engage in a classically interstate industrial war with China, the Russian Federation, or North Korea, we’re going to find ourselves immersed in the new war paradigm that British General Sir Rupert Smith brilliantly coined in 2005 as “war amongst the people.”3 The people are simultaneously a) the targets for terror; b) the power object of the insurgency and the government; c) the cover and concealment for criminal enterprises, and of course, d) the victims of the criminal organizations that feed upon them.

Most important to visualize is the fact that the “people” are not some uniform group, but are as diverse in their social perspective as they are culturally. Their ethnicities, races, educational levels, tribal affiliations, social histories and socioeconomic location may easily lend uniqueness to how they act and react to the terrorist, insurgent, or organized crime presence among them, as well as government sponsored efforts against those elements. Winning this side of the war is as essential as killing or prosecuting the enemy! This makes a monolithic military approach a set-up for failure from the beginning, particularly on the politically limited battlefield. It may be practically impossible to win the approbation of every demographic segment, but we should have a powerful and cohesive effort to do so that equals our offensive military and police efforts and we should never slacken or give up.

I respectfully assert that for purposes of network attack it does not matter if our enemy is defined as a terrorist, an insurgency, or an organized criminal enterprise. If a terrorist organization is robbing banks and armoured cars, growing opium or cocaine, and kidnapping innocent victims to fund their ideological cause, then they are criminals also. Ditto an insurgency.

Maintaining the Offensive – F3EAD, Nancy Reagan, and YouTube

I say this without apology. The U.S. and Coalition Forces in Iraq and Afghanistan did an absolutely horrible job of public relations during OIF and OEF. Conversely, the criminal insurgencies did and continue to do a magnificent job of propagandizing our every action. They do this because our current TTPs very dutifully feed their machine and we need to change this. We need to change this dramatically. In order to achieve and maintain the offensive, we cannot be constantly reacting to false allegations by the insurgency and attempting to morally or ethically justify our last operation and explain our actions. We should achieve and remain on the offensive both militarily and socio-politically and for this new paradigm we should take selective pages from the various chapters of The Book of What We Know Works Best.

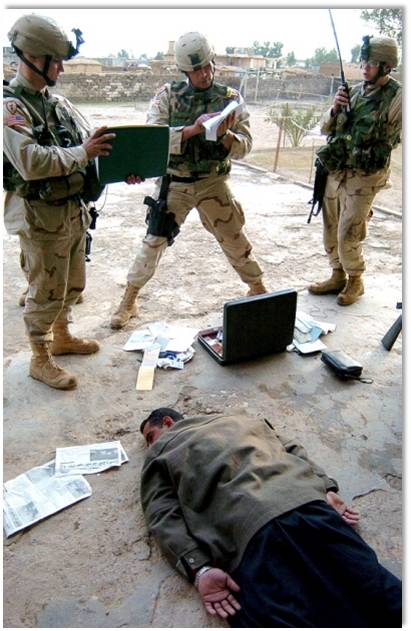

The special operations forces of the U.S. military use a strategic operating cycle known as Find, Fix, Finish, Exploit, Analyse, & Disseminate (F3EAD). Now, police have been doing this since Sir Robert Peel modernized the concept of the London ‘bobby’. You “find” the enemy through data mining, informants, and various technical means, and rank and scale his significance within the criminal network. You then “fix” his location through physical and/or technical surveillance and establish his pattern of life. When he is where you want him to be you then “finish” him traditionally through direct action such as a search warrant, arrest warrant, or seizure warrant; and untraditionally through kinetic operations. You “exploit” the location of his arrest through aggressive and tightly coordinated search and seizure. You then very rapidly “analyse” your evidentiary findings, starting at the crime scene itself and emphasizing any evidence that will take you to the next target before the enemy can react. You then “disseminate” the information to concerned end-users through rapid, summary reports.

The special operations forces of the U.S. military use a strategic operating cycle known as Find, Fix, Finish, Exploit, Analyse, & Disseminate (F3EAD). Now, police have been doing this since Sir Robert Peel modernized the concept of the London ‘bobby’. You “find” the enemy through data mining, informants, and various technical means, and rank and scale his significance within the criminal network. You then “fix” his location through physical and/or technical surveillance and establish his pattern of life. When he is where you want him to be you then “finish” him traditionally through direct action such as a search warrant, arrest warrant, or seizure warrant; and untraditionally through kinetic operations. You “exploit” the location of his arrest through aggressive and tightly coordinated search and seizure. You then very rapidly “analyse” your evidentiary findings, starting at the crime scene itself and emphasizing any evidence that will take you to the next target before the enemy can react. You then “disseminate” the information to concerned end-users through rapid, summary reports.

It achieves a strategic initiative that tends to keep moving forward as long as the process is diligently observed. I’ve used the strategy as a criminal investigator and HUMINT specialist, it works, and we need to expand its application.

Americans who remember the 1980s will remember the War on Drugs slogan “Just Say No” which aimed to dissuade children against entry into the cycle of drug abuse and was fronted by the public face of the former First Lady, Nancy Reagan. The campaign was simple, effective, and was largely credited with reduced marijuana use by U.S. high school seniors from 33% in 1980 to 12% in 19914 – a major success. It worked and we need to adopt this concept and adapt it for application to the GWOT.

As this article is being written, there are more people logged onto Facebook than there were people on planet Earth 200 years ago5. YouTube has become a global social phenomenon in itself, far transcending its two-dimensional application as a venue for personal exposition. The Western militaries must realize this and seize the opportunity with alacrity. An entire spectrum of social network messaging is possible through this global venue and only the apparently pathological phobia of the military towards manipulating this venue is preventing us from using it to actually shape cultural opinion and perhaps prevent wars and criminal insurgencies from escalating. Critical thinking military and strategic security executives everywhere must regard the recent Kony 2012 phenomenon for its staggering potential to shape the battlefield they will manoeuvre upon.

If we don’t shape the social battlefield, the criminal insurgents will. They are doing so at this very minute. YouTube works and we need to grab the concept, adapt it to fit the regional or cultural application we find ourselves operating within, and leverage the bloody hell out of it.

Summary and Recommendations – A New Operational Concept

I am proposing the development and implementation of a military hybrid adaptation of the highly effective U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) as part of a cohesive approach to CIED Network Attack. This new task force approach should not be operationally confused with the Joint Special Operations Task Forces (JSOTF), but it should plug in with the JSOTF for high-level targeting. The new hybrid task force construct should not be one-size-fits-all, but instead be strategically tailored to fit the specific CIED campaign within which it is applied so that one version may, for example, enjoy utility against the cartels in Mexico while regional versions may be applied against various extremist presentations in the Middle East and southwest Asia. The hybrid should combine proven military operational TTPs with strategic investigative principles. I’ll compare and contrast some similarities and differences between the proposed hybrid and the proven OCDETF concept.

Similarities

The proposed network attack hybrid should be oriented towards a primary prosecution of IED network members and affiliates within a legal jurisdiction determined in advance through collaborative strategy to be the most effective. Capture/Kill should remain a secondary prosecutorial option with clearly defined guidelines that are campaign-specific and adaptable.

The proposed hybrid should contain the same proven constituent components as its classic OCDETF progenitor, but be adapted to its new orientation and purpose. Representative specialists from every venue of network attack should be incorporated into the hybrid network attack task force. Investigative specialists from violent crime, organized crime, drug enforcement, smuggling, financial crime, electronic crime, local law enforcement, corrections, the forensic sciences, linguists, criminology, sociology, social anthropology, Interpol, and the International Criminal Court should team with regional prosecutors and military specialists in law, counter-insurgency, psychological operations, civil affairs, and (don’t laugh) specialists in business, economic, and international and commercial development.

Differences

The classic U.S. OCDETF is oriented towards prosecution within a Western (U.S.) Common Law judicial model that both legally sustains it and empowers it. The proposed hybrid task force concept recognizes that the developing world may lack the judicial infrastructure and legal framework necessary to provide outcomes consistent with task force operations and larger strategic geopolitical goals. For example, many countries do not even recognize conspiracy as a crime. The new task force therefore needs to carry its infrastructure and legal framework with it and this is where the lawyers can actually help us.

Goals

The goal of the hybrid task force is the neutralization of the criminal insurgency through both conventional and unconventional approaches that are consistent with strategic geopolitical goals. Cohesive efforts coordinated within the task force structure prevent counterproductive strategies and encourage consistency in TTPs that work. Those strategies include large-scale, embedded campaigns of public service improvement, social inoculation, anti-crime, and isolating insurgents from the public they need in order to survive and thrive.

This is 21st century warfare in the developing world and we have to fight it as such. We cannot move in force into an alien culture and expect the people to rally to our cause if we do not offer them something better to go with the removal of the criminal element that concerns us. I’ve spent my professional life in this field and I know this can be done. But until we reconfigure ourselves to accomplish this cohesively, the insurgent will continue to toil unhindered.

Edited by Richard de Silva

1Mcfeely, R. (2001, May). Enterprise theory of investigation, para 8. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin.

2FBI. (2012, April). Glossary of terms. Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/organizedcrime/glossary

3Smith, R. (2007). The utility of force: The art of war in the modern world, p. 280. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

4Bergman, L., & Levis, K (Writers). (2000, October 9). Drug wars. In L. Bergman (Executive Producer), Frontline. Boston: WGBH.

5Russel, J. (2012, March 5). Kony 2012. April 5, 2012 from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y4MnpzG5Sqc