In my opinion, one of the most important books written in recent years on the subject of the global arms trade and its corrupting effects is Andrew Feinstein's, The Shadow World, Inside the Global Arms Trade. This voluminous book is mind numbing in its detail, but it is thoroughly sourced and, I believe, it will become a standard reference over time. Anyone trying to understand the dark and dangerous corner of the global economy and its politics must read this book. (To be sure, I am biased because I was a minor source in this book and I consider Andrew a good friend.)

Naturally, the arms makers are not too happy with the Shadow World and want to keep it hidden in the musty stacks of your local library. I am attaching two recent essays to help you determine if this book should be forgotten. They were published on the Lexington Institute' Early Warning Blog. Lexington is funded in large part by defense contractors and is hardly impartial on all matters regarding defense spending, so the first essay is quite expected; the second, however, comes as a surprise, to Lexington's credit.

The first essay is a predictable critique of Andrew's book by Robert Trice, a retired Senior Vice President of Lockheed Martin. Think of his effort as an attempt to move Andrew's book to a forgotten corner in the back room.

To understand the saliency of Trice's effort, consider his career. Robert Trice is a case study in the quintessential pattern of gorging oneself on cash flow pumped out by the Military – Industrial – Congressional Complex's big green spending machine. Holding a PhD in political science, he began his defense career in the Office of the Secretary of Defense in the Pentagon, where he eventually became Director for Technology and Arms Transfer Policy — or in plain english, a resident shill in the Pentagon for promoting international arms sales — the subject painted in not so flattering terms by Feinstein. Trice then moved to Capital Hill and worked as the defense Legislative Assistant to Senator Dale Bumpers (D-AR) for about three years. I met him in this position because Bumpers was interested in the military reform work my colleagues (Pierre Sprey and John Boyd) and I were doing in the Pentagon. But Trice, as Bumpers' advisor, was clearly a reluctant reformer. (Although Bumpers showed initial and enthusiastic interest in our work, nothing came of it.) In the essay below Trice now slings a little mud, saying the three of us are not just wrong but wrongly motivated, because we are “anti-defense.” Soon thereafter, the presumably pro-defense Trice cashed out of Bumpers office to work in the Defense industry, serving first as a Vice President for Business Development at McDonnel Douglas (in plain english this is a marketing job and in the MICC, marketing, or business development, means greasing the skids in Congress and the Pentagon for your firm's tinker toys — which is a good position for a poly sci type, because he couldn't design airplanes at McAir or Lockheed). Trice then moved to Lockheed Martin where his business development portfolio including shaping L-M's new business strategies and operations for the global market, which of course is the subject of Andrew's book. Obviously a person with his background of bottom feeding so successfully in the MICC's money machine, especially in the international arms trade arena, comes to the reviewing table with … shall we say … a certain amount of bias.

The second essay is Andrew Feinstein's polite repost to Trice's bucket of grease. Andrew's background could not be more different than that of Trice. Whereas Trice gorged himself and became a wealthy ‘pillar of the establishment' by slopping in America's defense trough, Andrew put his ass on the line trying to rein in the excesses of that trough's South African equivalent. In the late 1980s, Andrew, a young white South African, joined Nelson Mandella's African National Congress (ANC), because he opposed Apartheid. In 1994, after the fall of Apartheid, he was elected in South Africa's first democratic election to be an ANC member of parliament. But Andrew took his parliamentary oversight responsibilities seriously, and while in parliament, he set up a kind of one man Truman Committee to investigate allegations of ANC corruption in some international weapons deals. And he hit pay dirt, but rather than shutting up when he was pressured by party elders to close down his investigation into a £5bn arms deal that was tainted by allegations of high-level corruption, he resigned in protest from Parliament. His political memoir, After the Party: A Personal and Political Journey Inside the ANC, was published in 2007 and became a bestseller in South Africa.

With the backgrounds of these two protagonists in mind, I urge you to read Trice's critique of Andrew's latest book first (Attachment 1 below) and then Andrew's repost (Attachment 2 below) and judge for yourself who is closer to being a straight shooter — and read The Shadow World.

Whole Enchilada (Both Articles) Below the Line

Attachment 1

Defense Executive Rebuts Flawed Accounts Of Global Arms Trade

Author: Robert H. Trice<

Date: Monday, January 23, 2012

Retired Lockheed Martin Senior Vice President Robert H. Trice was so incensed by the errors he saw in recent accounts of the global arms trade that he wrote this rebuttal, describing the real situation. Trice spent much of his career at Lockheed Martin and other defense companies marketing U.S. military technology overseas.

I write in response to John Tirman’s recent (Washington Post November 6, 2011) and generally positive review of Andrew Feinstein’s The Shadow World, Inside the Global Arms Trade. Feinstein provides genuinely interesting and insightful accounts of the illegal activities of clandestine arms merchants such as Bout, Mertins, Minin, Al-Kassar and the like. And his chilling portraits of the institutional corruption associated with the gigantic South African-UK-Germany-Sweden arms deal of 1999, Iran-Contra, the Gripen leases in central Europe and Al Yamamah and Al-Salam programs in Saudi Arabia appear largely accurate. But his attempt to expand this “shadow world” to include large, publicly-owned and traded American aerospace and defense companies is fatally flawed, and for the sake of future researchers his conclusions cannot go uncontested.

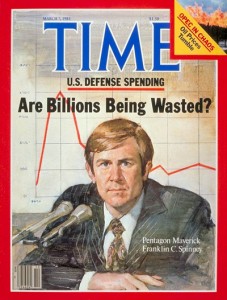

Feinstein’s description of the South African affair was based on his personal participation, and his secondary coverage of U.K. arms sales practices came from the solid, fact based research of Leigh and Evans of The Guardian. But he makes a terrible mistake by relying almost exclusively on William Hartung’s 2010 book, Prophets of War and a handful of tired and predictable anti-defense critics—Sprey, Boyd, Spinney, Fitzgerald, Wheeler—to characterize the U.S. defense industry of the 21st century.

Many of Hartung’s, and by extension Feinstein’s, assertions are the product of shoddy scholarship, unsubstantiated conspiracy theories and unfailingly biased judgments. Over and over they confuse the role of contractors who design and deliver weapon systems for sovereign governments with the deployment and use of those systems by civilian and military officials empowered to do so. Their central conclusions are 1) “…that the weapons business profoundly undermines American democracy, representing the ultimate beneficiary of the legalized bribery that proliferates on Capitol Hill” (p. 372); 2) there is a total lack of oversight and control over defense spending (p. 416); and 3) that defense executives can act illegally with impunity (p. 226). When defense budgets rise or systems are delivered late and not canceled, it’s the result of the insidious Military Industrial Complex and the inherently improper influence of industry.

But how about when procurement budgets decline, as they did from 1991-97, and are likely to do so for the next decade, or systems like the F-22 or the Future Combat System are cancelled, or big arms deals such as new F-16s to Taiwan are not made? How did these happen? Here the authors are at a loss because reality is not as simple as they would like it to be. Economic pressures, changing threats and requirements, program performance, politics, media coverage, personalities, lobbying and legislation all play a role in major defense decisions. Both Feinstein and Hartung recount that the F-22 was terminated on the basis of Secretary of Defense Robert Gates calling Lockheed Martin CEO Robert Stevens into his office and essentially saying, “If you oppose me on this, I’ll eat your lunch.” (p. 334). It’s a great story, supposedly relayed by “an observer with inside knowledge,” with only one problem; it never happened.

Both authors spend a lot of effort on historical case studies of bribery but Feinstein at least acknowledges that while repugnant, it was not illegal in the U.S. until passage of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in 1977 (pp 356-7), and U. K. anti-bribery laws did not take effect until 2002. Laws matter a lot and in the U.S. the combination of the FCPA, the Arms Export Control Act and Sarbanes-Oxley provide clear guidance to industry. Both repeatedly complain about a lack of transparency, but neither Feinstein nor Hartung ever note that every step of every sale of defense equipment to foreign governments requires a separate State Department export license, and every proposed sale of $50 million or more is reviewed by Congress. Every fall the Administration is required to send Congress the so-called “Javits report,” in which all major arms transactions that could occur in the next fiscal year are listed and form the basis for dialogue and negotiation between the executive and congressional branches.

Feinstein’s accounts of bribery scandals are entertaining, but he fails to discuss what the U.S. Government has done to address the issue. The most effective way to prevent bribery is to keep the recipient’s money separate and distinct from the money received by the provider of defense goods and services. Such an approach denies the provider the resources required for any potential illegal commissions, “slush funds” or “kickbacks”. And this is exactly what the U.S. Government’s Foreign Military Sale (FMS) system does. Under FMS, the U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) and the relevant military service negotiate with the U.S. company on behalf of the foreign government recipient. The contract is between the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and the American provider. Goods and services are delivered to DoD which then transfers them to the foreign recipient. The arrangement between the U.S. and foreign governments is in the form of Letter of Offer and Agreement (LOA) documents, under which the foreign recipient agrees to pay in advance into a U.S. government trust fund held on its behalf. As items are delivered, DSCA draws funds from the country’s account and pays the contractor. DSCA charges a fee to the recipient to administer the program, and many governments in the developing world are comfortable paying this modest premium to avoid any possible charges of corruption. American contractors prefer FMS arrangements when dealing with countries where potential corruption is possible and/or future cash flow could be an issue. For countries with more advanced acquisition systems that do not want to pay the FMS surcharge, the alternative is a Direct Commercial Sale (DCS) between the contractor and the foreign government, with the same U. S. government licensing, auditing and oversight requirements. It is amazing that these “insider accounts” of the arms trade never mention the FMS and DCS mechanisms, each of which account for roughly half of America’s defense exports.

Concerning oversight, contrary to the picture painted by Hartung and Feinstein, the U.S. defense industry is among the most highly regulated business sectors on the planet. More than 4,000 employees of the Defense Contract Auditing Agency (DCAA), 10,000 civilians in the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA), and 1,475 auditors in DoD’s Office of the Inspector General work in support of the Office of the Secretary of Defense acquisition community, individual service program management offices and Congress’ auditing arm, the General Accountability Office (GAO), to ensure the taxpayers’ monies are protected. In addition to all these agencies, protected whistleblowers in both government and industry, a knowledgeable and aggressive media devoted to aerospace and defense, and legions of independent think tanks and headline-seeking congressmen and their staffs make for an ongoing and vigorous public debate on almost every topic related to American defense policy.

Feinstein’s repeated assertions that defense executives are “above the law” (p. 278) and act with impunity certainly do not apply in the U.S. and are undermined by his own examples. The procurement scandals he describes involving Congressman Duke Cunningham, Darlene Druyun, Michael Sears, Mitch Wade, Dusty Foggo and others all ended with jail time. Iran-Contra resulted in 11 Reagan administration officials, including the Secretary of Defense, being convicted for their illegal conduct.

Hartung’s numerous factual errors taint the credibility of Feinstein’s work. Lockheed Martin did not provide interrogators to Abu Ghraib or Guantanamo Bay (p.414). Romania has not bought any F-16s, much less $4B worth (pp 337-8). Northrop Grumman, not Lockheed Martin, built the ships for the Coast Guard’s Deepwater program (pp. 339-40). The competition for the Littoral Combat Ship was between Lockheed Martin and a General Dynamics/Austal team, not Northrop Grumman (p. 340). Bruce Jackson, who Hartung and Feinstein claim was Lockheed’s principal and secret salesman to NATO and Iraq, was never Vice President of International Operations (p. 289), much less CEO Norm Augustine’s “successor” (p. 290). He was a staff vice president in the corporate strategic planning department with absolutely no marketing role. On his own time, he was also Chairman of the U.S. Committee to Expand NATO, a privately funded interest group. He left Lockheed Martin in 2002 and co-founded the Committee for the Liberation of Iraq. The implication (p. 395) that he did so to somehow benefit his former employer is untrue. The bold but unsupported declaration that, “After KBR, Lockheed Martin was the second largest contractor to the U.S. in Iraq and Afghanistan” (p. 414) is simply wrong. Hartung’s and Feinstein’s depiction of former CEO Norm Augustine as lobbyist and powerbroker (pp. 287ff) is a laughable caricature and a disservice to a lifetime devoted to advancing the common good. In contrast to their description of the Polish F-16 program (pp. 291-1), had either bothered to ask Polish or U.S. government officials they would have found it to have been highly successful in all respects, without a hint of corruption, and has resulted in Polish pilots routinely and safely flying the most advanced fighters in Europe.

Finally, credibility requires some degree of objectivity concerning one’s subject. But Feinstein’s and Hartung’s passionate antipathy for most everyone associated with weapons systems acquisition of any kind, from notorious criminals to military officers to congressmen to CEOs of Fortune 100 companies, is palpable and makes it difficult for readers to distinguish fact-based insights from cynical hyperbole and misstatements. At one point Feinstein says, “I can’t imagine…any defense industry executive, grappling with the fundamental problem of whether it is even possible to be an ethical arms company” (pp 149-50). Having spent 28 years in the business, I can attest that this is exactly what I and hundreds of my colleagues and competitors in the senior ranks of U.S. aerospace and defense industry do every single day. Transgressions by heritage companies a half century ago cannot be defended or excused. But 21st century American aerospace executives are committed to setting and maintaining the highest legal and ethical standards. Lockheed Martin’s code of ethics and its annual compliance training for all employees, beginning with the CEO and his direct reports, are a world standard for global industries, and have been for the last 15 years. Rather than impugn the integrity of those who provide critical systems and support to those entrusted to protect the nation and its allies, we would all be better served by a more balanced analysis. But that would require a degree of objectivity and generosity of spirit that elude both Hartung and Feinstein.

——————–

Attachment 2

Author of Arms Trade Book Responds to Critique from Defense Executive

Author: Andrew Feinstein

Date: Wednesday, February 15, 2012

On January 23, the Early Warning blog published a critique of Andrew Feinstein's book, The Shadow World: Inside The Global Arms Trade by retired Lockheed Martin Senior Vice President Robert H. Trice. Author Feinstein responds below with a rebuttal to the Trice critique.

I write in response to retired Lockheed Martin (LM) Senior Vice President Robert Trice’s critique of my book The Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade.

Given his background, Mr. Trice has a personal and vested interest in defending LM and defense contractors generally. However, his years in the industry might have led him to believe it is possible to have ones cake and eat it. In the case of meaningful criticism of research it is not.

Mr. Trice praises what I have written on everything but the US arms industry and expects his reader to accept that I have got the US dimension wrong on the basis that I draw heavily on the work of Bill Hartung.

Hartung’s work on the US defense sector has been rightfully praised and used extensively in the US and abroad. However, in my book of 500 pages with over 2,500 references, I have drawn on a wide variety of sources. In the US sections I have used material from hundreds of researchers, writers, journalists and interviewees. They include long-time current Capitol Hill staffers, former Pentagon insiders, senior retired military personnel, government officials from a wide range of agencies and whistle-blowers. Are they all wrong, or is it that they present a different, perhaps more objective, picture of the industry than someone who has spent 28 years in its upper reaches?

It is important to note that LM declined to comment on Hartung’s work or my own when approached during the writing of our books.

Mr. Trice praises my account of the illegal arms trade but disregards the linkages between it and the formal trade he defends. He ignores my evidence that illicit dealers such as Viktor Bout and many others have been used as contractors by both the US government and major US companies as recently as the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. He overlooks the detailed documentary evidence I cite which reveals that such practises have been common since the birth of the modern arms trade and intensified after WW II when the US government and companies became bed-fellows of a range of insalubrious characters including former senior Nazi officers.

While commending my work on corruption in major arms deals, Mr. Trice then denies it applies to the US in the past or present. He fails to mention the calculation by Transparency International in two separate studies, that the global arms trade, which the US dominates, accounts for between 40% and 50% of all corruption in all world trade.

I acknowledge in the book that the US and its defense contractors, which led the way in arms trade corruption in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, has cleaned up its act since the strengthening of the FCPA – legislation which American industry is now trying to weaken. However, this improved conduct neither alters the history nor diminishes the need for continuing vigilance. The Polish deal which I quote allegedly involved inappropriate US political and economic pressure and possibly corruption. [To set the record straight, my information on this deal is based on my own primary sources not Hartung.] The sections on Iraq and Afghanistan document the horrendous levels of malfeasance in recent contracting. And the case of BAE Inc, which was recently forced to admit to paying ‘unauthorised commissions’ in six weapons transactions is but the most obvious indicator of the need for vigilance.

Mr. Trice’s unfortunate views on bribery and corruption prior to the FCPA are a damning indictment of the ethics of the defense industry.

In the most blinkered of his criticisms Mr. Trice is unable to accept or comprehend what President Eisenhower and many others have revealed repeatedly: the cosy relationship between defense contractors, the Pentagon and political decision-makers, which was described to me, not by Hartung but by a long-time Capitol Hill staffer, as ‘legalised bribery’. The movement of senior Pentagon officials into the lucrative employ of contractors to whom they have often awarded major weapons projects in their careers, and the significant campaign contributions these companies make to the very law-makers who are required to approve and monitor these projects, would break the law in many of the world’s democracies.

I argue that this self-perpetuating circle of patronage has, on occasion, resulted in the commissioning of inappropriate weapons projects, wastage of public funds, poor quality standards and missed deadlines. The ailing F-35 project is only the latest, most expensive, manifestation of this.

In addition, as an outsider with experience of developing public sector financial management systems, including as an MP in South Africa under Nelson Mandela, I am shocked by the lack of meaningful checks and balances in the interaction between the Pentagon and defense contractors. Last year the Pentagon, which has not been properly audited for over two decades, informed Congress that it would miss an imposed deadline of 2014, but suggested it might be audit ready by 2017!

The uniqueness of the trade in weapons is that it is regulated by the very people who are complicit in the problem. This is why so many defense companies and arms trade intermediaries around the world either do not face meaningful justice when they have broken the law or suffer inadequate penalties for their transgressions when they occasionally do. Iran-contra is only the most obvious example. I document not only myriad company transgressions but also the misdemeanours of countless middlemen, many with connections to defense companies, intelligence agencies and other arms of government – who rather than being prosecuted are often generously rewarded for their illegality.

Mr. Trice suggests that the publicly-known cases I do present show how effectively the checks and balances are working. He entirely misses my point and much of the content of the book about the plethora of cases that never make it into the media, let alone the courts. The careers of most of the illicit arms dealers I cover, who also do work for defense contractors, makes exactly that point. As does the fact that when an Iranian arms intermediary was brought to the US to stand trial he revealed that literally hundreds of US defense contractors were selling illegally to Iran. They were let off the hook.

The cases that do make it into the public domain are, given the levels of corruption in the industry, the exceptions that enunciate the systemic problem. And how Mr. Trice regards the case of Boeing as an example of how well the system is working, is unfathomable. The company caused the cancellation of a tender process for tanker refuellers due to illegal and grossly unethical conduct but then still won the subsequent tender, from which in a more appropriately regulated environment it would have been excluded.

I have experienced through my involvement in investigations how even the best laid plans, with far more stringent checks and balances than exist in the US, have been undone by the use of secretive middlemen, offshore accounts, industrial offsets, and the symbiotic relationships between procurers, producers and governments.

Crucially, oversight arrangements for the industry are seldom open to meaningful public scrutiny. Most of the agencies Trice mentions as part of the regulatory structure were not prepared to talk to me about their work. Perhaps that’s why no one writes about them.

On the quantum of defense spending, Mr. Trice disregards the detailed analysis I provide. I note the volatility in spending but, as an economist with training from Cambridge University, the London Business School and the University of California at Berkeley, I am able to discern the significant upward trend of spending over decades and the reality that the US spends almost as much as the rest of the world combined on defense and national security. These facts are borne out by countless US and international experts.

Bill Hartung has separately dealt with most of the factual issues that Mr. Trice raises, quoting the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan who noted that “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.” To impugn work without providing alternative facts is disingenuous. If he would like to present me with additional information I would happily consider it.

I personally had no preconceptions about the industry before being forced, as an elected representative, to deal with its consequences. I witnessed the impact of it on South Africa’s young democracy and discovered, during my decade of research, that that experience was hardly unique. The manufacture and trade of weapons has brought immiseration, massive opportunity cost, corruption, and the undermining of accountable democracy and the rule of law in both buying and selling countries. Perhaps almost three decades in the industry makes it more difficult to see these consequences.

Andrew Feinstein

See Also:

1961-2011: 50 Years of The Military-Industrial Complex

Chuck Spinney: Bin Laden, Perpetual War, Total Cost + Perpetual War RECAP

Marcus Aurelius: US at Permanent “War” + War RECAP

Reference: The Pentagon Labyrinth

Review: Defense Facts of Life–The Plans/Reality Mismatch

Review: Prophets of War–Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex

Review: The Military Industrial Compex at 50

Winslow Wheeler: ONE COLONEL TELLS THE TRUTH – Major Investigation Called For + Meta-RECAP