Unless the international community demonstrates it is serious abouthuman rights, restitution and disrupting organised crime and criminality, its current policy of stability in place of justice can only continue to fuel both injustice and instability.

Learn more about the principles of conflict transformation!

TransConflist, 4 October 2012

By James McDonald

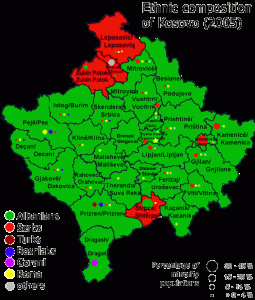

Click on Image to Enlarge

On 28 June 1999, Petrija Prljević, a 57 year-old woman in Pristina, was abducted from her apartment by men dressed in KLA uniforms. She was never seen alive again: a year later, her body was exhumed from a cemetery in Kosovo’s capital and positively identified by her son after he recognised items of her clothing. The job of finding out who caused her death was not investigated by the new prosecutors’ office on the basis that she died after the “war” in Kosovo had ended; instead it was investigated by the Eulex Rule of Law Mission. Over ten years later her relatives are still trying to find out what happened to her and who was responsible. Eulex seem no closer to launching an investigation to identify and prosecute her murderers, like the vast majority of the more than 1,000 other cases of murdered Serbs since NATO forces entered Kosovo. Contrast this with the efficient way in which Eulex’s Rule of Law Mission initiated investigations to find the persons responsible for the killing of a member of ROSU in summer 2011. As a recent Amnesty International report made clear, murders continue to be carried out with impunity under the gaze of an international community which seems peculiarly reluctant to investigate them. Indeed, while numerous Yugoslav officials have been tried and convicted for crimes against humanity committed by security forces under their command prior to June 1999, the fact is that of the more than 1,000 Serbs who have been killed since the end of the conflict, almost none have resulted in a prosecution, let alone a conviction. On the contrary, according to the testimony of some international police officials who have worked in Kosovo, there have been active attempts by some elements of the international administration to obstruct investigations, especially when they have threatened to implicate high-ranking Kosovo politicians.

It now seems a long time since Dick Marty’s report exposing the complicity of leading members of the Kosovo Albanian political elite in war crimes, crimes against humanity and organised crime. If anything symbolised the impunity which Albanian politicians in Kosovo still enjoy – and are likely to enjoy for the foreseeable future – it was the recent acquittal of Kosovo politician, Fatmir Limaj, a member of Hashim Thaci’s Democratic Party of Kosovo, of war crimes committed at the KLA Klečka camp; the case collapsed following the coincidental deaths of more than a dozen witnesses, including the suicide of the main witness, Agim Zogaj, although a staggeringly incompetent prosecution probably didn’t help. Likewise, the ongoing second war crimes trial of Ramush Hardinaj, former KLA guerrilla commander, founder of the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo and one-time prime minister of Kosovo, has resulted in numerous key witnesses mysteriously losing their memories, refusing to testify or conveniently dying. Kosovo must have the highest traffic mortality, Alzheimer’s and suicide rates in the western world.

Kosovo is a Kafkaesque state. Ruled by two dominant clans who also conveniently head the two main political parties – the Democratic Party of Kosovo and the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo – it is a state in which the economy and most political relations are built on organised crime and in which extravagantly wealthy politicians preside over a society with endemic levels of poverty and unemployment. The prime minister, Hashim Thaci, and much of his government are believed to be deeply implicated in organised crime in the state and are alleged to use intimidation, murder and a complex clan and patronage system to silence dissent. At the same time the government – and Thaci especially – talk of bringing “the rule of law” to a Serb-dominated North through the destruction of the criminal gangs which allegedly control life there. The prime minister and his youthful cabinet loudly proclaim their fidelity to the principles of democracy and freedom as the “Young Europeans”, while at the same time routinely describing a section of their own population’s demand for self determination as “terrorism” and “criminality”. It is a state which publicly adheres to liberal principles but in which citizens from minority communities can be arrested for being in possession of the wrong car registration plates or even an election placard. The Kosovo police, meanwhile – whose job it is to uphold the law – have found themselves under arrest, accused of fomenting anti-state sedition or undermining the constitutional order (in the case of ethnic Serbs) or (in the case of ethnic Albanians) being reduced to the role of party Praetorian guard in a hopeless attempt to effect the enforced assimilation (or as international officials would have it “integration”) of the Serbs and other recalcitrant minorities.

While EULEX holds expensive conferences on such pressing concerns as gender equality awareness and sponsors opinion polls which aim to provide, in the best policy-based tradition, empirical evidence for their belief that Serbs, Roma and other minorities really like living in Kosovo, those same minorities continue to live in often appalling poverty – some of them in makeshift donated containers – in heavily-guarded ghettos unable, in some cases, even to send their children to school. It is, in short, a classic example of what David Chandler termed “faking democracy”. In its current form Kosovo has about as much of a relationship to democracy and the rule of law as the “democratic” Latin American regimes so beloved of the US State Department in the 1970s; they also practised symbolic and entirely meaningless democratic rituals in the midst of grinding poverty, endemic corruption and systematic human rights abuses.

Kosovo is the recipient of huge amounts of investment and aid – much of which, inevitably, never reaches its intended destination – as well as regular visits by optimistic European and US politicians extolling its supposedly multi-ethnic tolerant society. On 7 July at an international conference in Dubrovnik, Philip H. Gordon, a senior US official, stated that Serbia would have to “come to terms with the reality of a democratic, sovereign, independent, multi-ethnic Kosovo with its current borders”. As if to put such sentiments in their proper perspective, on the same day two elderly Serbs, Milovan and Ljiljana Jevtić, were murdered in Uroševac. Kosovo police spokesmen immediately rushed to reassure the international community that the killing was not ethnically motivated although how they could be so sure so quickly was not entirely clear given that so many killings in the state since 1999 have been. A few days earlier in Vienna, the International Steering Group (ISG), comprised of leading contact countries including the US, Germany and UK, announced that in mid-September Kosovo would be granted full independence. It was a sign, the Austrian foreign minister asserted, of the international community’s confidence in Kosovo and its belief that it was ready to assume responsibility for the future of “all its citizens”. It is also reasonable to suppose, however, that it is also a signal that European states – unofficially, naturally – have given-up on the attempt to make a normal state in Kosovo but are nonetheless anxious to declare a foreign policy “success”. Officially, therefore, current plans to integrate Kosovo into wider international institutional structures involve tackling corruption and preparing the state for eventual entry into the EU.

With the recent election of Tomislav Nikolić to the Serbian presidency, negotiations between Serb and Kosovo Albanian representatives stalling badly and a recent report by the Kosovo Albanian think-tank KIPRED predicting the likelihood of future unrest in Kosovo, especially if some kind of deal is struck to grant the North self rule, it is worth considering the reasons for the surreal upbeat attitude of the ISG, the EU and US State Department in the face of the disastrous situation in Kosovo. One obvious answer is expediency. With the Middle East in crisis and a conflict with Iran looming, it is perhaps natural that states with troop shortages will seek to declare a disaster zone victory and exit with at least some semblance of dignity. This would explain the transformation of KFOR, in particular its German contingent, from a peacekeeping force to what is – essentially – the armed police of the Kosovo government. Proactive in the past year in trying to change facts on the ground in favour of the Thaci administration, it has spent most of its time since not building bridges between the two communities, but attempting to destroy Serb barricades and force the fearful Serb community in the North into compliance with Thaci’s plans for “integration” via a Potemkin Village administrative office. (Again, this stance makes for a striking comparison with the 2004 anti-Serb riots when German troops were accused, in a scathing police report to the German government, of allowing Albanian extremists to go on the rampage against Serbs and other minorities.)

Of course, it’s not all bad news; there has been some progress since the terrifying months of summer 1999 when the Yugoslav authorities and KLA competed in mass terror and war crimes or the anti-Serb riots of March 2004. But an improvement on violent anarchy can hardly be counted as a success. Clutching at straws, western officials point out that there is now a Serb party in coalition with Thaci’s DPK. True, but the Independent Liberal Party of Slobodan Petrović is widely-viewed as a clannish corrupt party of Kosovo Serb businessmen mirroring the structure of the dominant ruling Albanian parties. Moreover, its junior ministers have often been reduced to the role of willing puppets of the DPK with the deputy minister of labour, Nenad Rašić, even having to publicly agree to the construction of monuments decrying the “oppression” of Serb rule and glorifying the struggle of the KLA – an organisation which is implicated in the killing and disappearance of large numbers of Serbs. When allegations of bribery and vote rigging are added in, it is questionable how representative the SLS really is. While commentators and officials regularly cite the supposed “integration” of the Serb communities in the South as a sign of progress – in contrast to the noisy and unreasonable irredentism of their northern brethren – the compliance of the southern Kosovo Serbs is as likely a reflection of nervousness, and even fear. This is hardly a record on which a “tolerant multiethnic” society can be built.

Most officials who are involved in Kosovo will admit the enormous problems Kosovo faces: the systematic human rights abuses; the endemic organised crime and corruption; and, most recently, the sponsoring of violent groups in Macedonia and the Preševo Valley by hardline elements of the KLA. Officials acknowledge that, given the political reality on the ground, organised crime and corruption will possibly never be brought under control by accepted international standards. Therefore, in the same way that Kosovo’s democracy has been “managed” on its own terms, so the success of the EU’s anti-corruption and organised crime initiatives will be measured against Kosovo’s own internal benchmark. Lest this be termed a policy of resignation, officials have privately expressed the hope that while the current generation of Kosovo politicians might be irredeemably corrupt and antidemocratic, the next generation should be more liberal. Yet how a generation brought up in an endemically corrupt society in which social mobility depends on those very same structures can escape the culture of corruption has not been explained. Furthermore, there is little evidence that the generation of embryonic Kosovo politicians currently studying for advanced degrees in political science at European or American universities are any less hardline on minority rights than their older peers. If anything, the evidence points in the opposite direction. Following the rhetoric of Thaci, Rexhepi, Kuci et al, they too – if their Twitter accounts or published essays are any guide – regard separatist Serbs in the North as “terrorists” and “criminals”.

How to explain the dissonance between the public proclamations and the tawdry reality? The unreality of the official western rhetoric regarding Kosovo has its origins in the original military intervention. Going to war on the basis of unreliable – and, in some cases, false – evidence, NATO countries believed wrongly that the Yugoslav government would capitulate in a matter of days. “We don’t see this as a long term campaign,” Madeline Albright infamously stated. The war was sold in the early stages of the bombing campaign as a means of returning Yugoslavia to the negotiating table, despite the warnings of intelligence analysts and experts that it was likely to have precisely the opposite effect. When the predicted Yugoslav attempt to crush the KLA through a brutal scorched earth policy involving forced deportation, mass killing and ethnic cleansing came to pass, the rationale for intervention then became one of preventing, in Tony Blair’s words, “hideous racial genocide,” in order to reverse a situation which NATO’s own intervention had precipitated. After Yugoslavia capitulated and NATO entered Kosovo victorious, with ethnic cleansing, mass killings and abductions by the KLA and their supporters raging through the province, the UK defence minister George Robertson declared that the “Allies” would work to create a tolerant, multiethnic Kosovo. The 2004 anti-Serb riots, the flight of over 150,000 Serbs, continued attacks against minorities and, above all, the decision to place final status before human rights standards (in complete opposition to the original stated policy) have given the lie to such lofty aims.

In recent months, it has become received wisdom to claim that the key to a settlement in Kosovo is the resolution of the situation in the North, hence the emphasis on pressuring Belgrade into ending funding for “parallel structures”. This is incredibly simplistic. In fact, the focus on the North obscures the far wider, more serious challenges of confronting corruption and criminality across Kosovo. In the belief that the fate of the North will decide the future of Kosovo itself, the international community has been busy formulating a new plan for the troublesome enclave. The details remain unclear but the key points seem to involve a version of “Ahtisaari Plus”: a regional parliament with limited powers over education, culture and health to be overseen by four elected ombudsmen; an amnesty by the central government for those in the North who have not paid utility bills; and an increase in the number of reserved Serb representatives in the state parliament, with guaranteed places for politicians from the North. In return, North Kosovo Serbs would be expected to give up their “parallel structures” and integrate into the Kosovo state. The flaws in this too-neat plan are obvious. It is highly unlikely to be acceptable to northern Serb leaders who have long since indicated, along with substantial numbers of Serb civilians, that they will never consent to be part of a state they consider illegitimate. Letting people off non-payment of past water bills is not going to change that. Nor, for that matter, will offering Serbs a few more seats in a parliament be any kind of real inducement: not just because that parliament represents a state whose existence they reject, but also because it is dominated by parties many Serbs consider responsible for their persecution and dispossession.

At the same time it is not hard to see why “autonomy lite” might appeal to the EU. Over and above the EU’s stated objection, on principle, to any further changing of national borders in the “Western Balkans” or elsewhere (a principle which, of course, the Kosovo intervention fundamentally undermined), any form of meaningful autonomy might have two unwelcome consequences. It would undoubtedly lead to a reaction against Serbs in the South by some Albanians and – perhaps more importantly – against the Kosovo political elite on whom the international community has placed such high hopes and invested so much effort. It might also see a move to the North by Serbs and other minorities living a precarious existence in vulnerable enclaves in central and southern Kosovo. Both of these processes would expose the abject failure of the western project to bring multiethnic and democratic values to Kosovo. But the international community has only itself to blame for the mess it now finds itself in. Since 1999, in the name of stability and protecting its protégés, its military and political structures in Kosovo have proven to be either unwilling or unable to defend the human rights and security of Serbs, Roma and other minorities and either unwilling or unable to prosecute those who have victimised them. In such a context, it is hardly surprising that many Serbs in the North are completely unwilling even to consider being part of such a state. Contrary to what many foreign policy advisers appear to believe, the North is less the cause of Kosovo’s problems and more a symptom, a microcosm for everything that has gone wrong in the past 15 years of international supervision.

What is to be done? For any lasting durable peace leading to the withdrawal of western troops, KFOR, in particular, needs to establish trust with the Serb population in the North, something which cannot be achieved by fiat, far less diktat from Belgrade, no matter how much some German parliamentarians wish it could be. First, both KFOR and Eulex could make a start by ceasing with the myth that the Serb resistance in the North is being led by criminal gangs. Criminality is clearly present in the North as it is elsewhere in the state, but it is not driving Serb separatism: fear and distrust are. Likewise, dismissing legitimate and understandable Serb aspirations for self determination cannot be wished away by dismissing them as “terrorism”, “criminality” or “political manipulation from Belgrade”. Until the international community tries to understand the root causes of the current recalcitrance in the North nothing of any substance – beyond clichéd slogans and ridiculously optimistic predictions – will be achieved. Second, and more fundamentally, Eulex should realise that it can’t hope to build trust between Serbs and the Kosovo state until tackles the primary factor driving Kosovo’s instability and poisoned ethnic relations: the endemic corruption and violence promoted by its ruling elite. The alternative, in the name of stability, is to continue playing the role of mentor to the current generation of Kosovo politicians. Taking the latter approach will mean that the only viable way to integrate the North – and therefore the Serbs who live there – will be through force and coercion.

From the perspective of an international community which is desperate for an exit strategy and a shiny foreign policy “success”, the forced reintegration of the North might solve the problem of how to bring the troops home from Kosovo. True, an exodus of Serb civilians and the inevitably ugly violence which might be visited on those Serbs who can’t or don’t want to leave would not do much for the EU or NATO’s moral credentials. But, as Operation Storm proved, crimes against humanity tend to be overlooked if government has good PR or the ear of sympathetic State Department officials. Fundamentally, however, it would fail to address the underlying causes of instability and conflict, causes which are intimately connected to the very nature of the state which has been developing under western supervision for the past 15 years. Solving the northern “problem” would leave a much bigger one in its wake: an inherently unstable state at the centre of organised crime in the region, dominated by a corrupt, criminal and unpredictable political class and one, moreover, linked to violent separatist and extremist movements elsewhere in the region. Pretending all is well or hoping vainly for a more enlightened younger generation to emerge is the politics of desperation and is a recipe for ensuring that political life in Kosovo will continue to be characterised by power without responsibility and crime without punishment. For the son of Petrija Prljević and the many others whose relatives’ deaths have gone uncondemned, unreported, unpunished and uninvestigated, any perception that the rule of law exists has probably long since evaporated. Yet the fact remains that unless the international community demonstrates it is serious about human rights, restitution and disrupting organised crime and criminality, its current policy of stability in place of justice can only continue to fuel both injustice and instability.

James McDonald is a UK-based international research analyst, with a specialist interest in the Balkans.