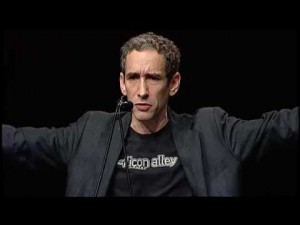

Editor's note: Douglas Rushkoff writes a regular column for CNN.com. He is a media theorist and the author of the new book “Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now.”

(CNN) — When I was a kid, I remember a guy named Daniel Ellsberg leaking some classified documents to the New York Times about the Vietnam War called “the Pentagon Papers.”

When the whistle-blower finally stood trial for espionage, my parents weren't quite sure how to feel. But when Richard Nixon's crew was revealed to have been conducting illegal wiretaps in an effort to discredit the former intelligence contractor, well, they were outraged and decided Ellsberg was a hero. So did the judge and most of America.

I wonder whether Ed Snowden, the 29-year-old Booz Allen Hamilton employee behind last week's series of leaks about National Security Agency surveillance on the American public, will be rewarded with the same admiration. You'd think we would be even more outraged by what he uncovered than we were by the surveillance of Ellsberg. After all, it's not just one lone loose cannon being wiretapped here, it's all of us being monitored.

Snowden has not uncovered a human conspiracy here but the workings of the machine itself. And it's a machine that really does require some human intervention.

In the coming months, I expect a campaign to be waged against this young man that will make the one against Ellsberg look like child's play. His enemies have the full force of the machine — every e-mail he's written and every phone call he's made — to use against him. This won't be pretty. But before we decide that Snowden was smiling too much in his videotaped interview with The Guardian, earned too much money or somehow betrayed his lovely girlfriend in Hawaii in a personal vendetta against his former bosses at the intelligence agencies, let's take just a moment to consider his particularly human act of heroism.

There are dozens, if not hundreds, of government employees and contractors who have long been aware of the NSA's total surveillance effort.

As a digital technology writer, I have had more than one former student and colleague tell me about digital switchers they have serviced through which calls and data are diverted to government servers or the big data algorithms they've written to be used on our e-mails by intelligence agencies. I always begged them to write about it or to let me do so while protecting their identities. They refused to come forward and believed my efforts to shield them would be futile. “I don't want to lose my security clearance. Or my freedom,” one told me.

Snowden was willing to take those risks and, I daresay, more.

Yet it wasn't just fear keeping people from talking about the growing cybersurveillance state but a sense of inevitability. This is just how technology evolves, at least when it's uncontested. Everyone knows, or should know, that everything we type on our computers or say into our cell phones is being disseminated throughout the datasphere. And most of it is recorded and parsed by big data servers. Why do you think Gmail and Facebook are free? You think they're corporate gifts? We pay with our data.

In such an environment, it's hard to come down too hard on government intelligence officers who want to get in on this action.

Our leaders are suffering from what I call “present shock”: the overwhelming assault of multiple threats from everywhere at the same time, amplified by technology of all sorts. Terrorists have unprecedented access to weapons of mass destruction and work through decentralized networks around the clock. As data-gathering tools emerge with ever-increasing ability to keep tabs on the world's communications, how can an overburdened intelligence agency choose otherwise than to exploit their potential?

The rush to employ technology has become automatic.

Called a defector, leaker defends his decision

We all know the feeling of surrendering to the embedded biases of our devices. We let our cell phones ping us every time there's an incoming message and check our e-mail even when we'd best pay attention to what's going on around us in the real world. We text while driving. Likewise, without conscious restraint, government agencies can't help but let the growing power of big data draw them into ever more invasive forms of surveillance on a population whose members simply must include those who intend harm on the rest. This is just how everything runs when it's left on “default” settings.

Yet if we let the evolution of our machines dictate the evolution of our policy, the only possible result is what Snowden calls “turnkey tyranny.”

As I have argued in other contexts, the best weapon against the paralysis of technologically induced present shock is human intervention. Just as we the people stood against the structural tyranny of an overreaching monarchy, it is we the people who must stand against the structural tyranny of runaway technology.

Snowden is a hero because he realized that our very humanity was being compromised by the blind implementation of machines in the name of making us safe. Unlike those around him, who were too absorbed in their task to reflect on their actions and pause in their pursuit of digital omniscience, Snowden allowed himself to be “disturbed” by what he was doing.

More in the midst of technology than most of us will ever be, Snowden disengaged for long enough to be human and to consider the impact of what he was helping build. He pressed pause.

Thank heavens our intelligence agencies are staffed by people like Snowden, not robots. People can still think.

That's why they call it intelligence.