Jonathan Lyons

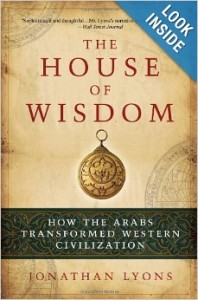

![]() A Few Inconvenient Details about Western History, October 29, 2013

A Few Inconvenient Details about Western History, October 29, 2013

Herbert L. Calhoun

For centuries after the fall of Rome, Western Europe was unaccountably still locked in the dark ages, a period referred to as “dark” for good reasons. Despite the rich intellectual heritage from both Greece and Rome, it is not well known that little of it had seeped into the medieval feudal and violence-torn Western European veins before the thirteenth century. Even less well known is that what little did seep in came by way of the rich history and cultural institutions of the Arab dominated Near East, a region that drunk the intellectual wines of both Greece and Rome nearly a millennium earlier than the West did.

Although Western Europeans were ever ready to fight each other, most of them could not read, write or tell time. There were only a handful of libraries. Neither streets nor people had unique names or numbers. Violence and instability were the order of the day. Even as the Kingdom and the Catholic Church viciously vied for power, Europe was essentially a region being run by “outlaws,” the equivalent of petty warlords that we see today in places like Afghanistan.

By the time Pope Urban II called for the first Crusade, feudal Europe had descended almost into anarchy. It was due in large part to this instability — involving a combustible mixture of church politics, theological disputes and feudal rebellions — that stimulated Urban's call to crusade. His primary appeal was to end the ceaseless internecine warring and turn their murderous energies on the “unbelievers” of the East — and by the way, get a remission of your sins as part of the bargain. Urban and his supporters within the church saw the Crusades as a way to restore the authority of Rome at the head of the Christian world without having to rely on unruly and competing monarchs.

When the English nobleman, Adelard of Bath England, arrived in Antioch in 1114, he was there to extend his education. As he put it: I went there to learn from the muslims, not to kill them. This book tells the story through Adelard's eyes of how he acquired the education and wisdom he sought in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. Adelard was the first to bring the wisdom of the Greeks and Romans back from Baghdad to the West.

While the West was still being run by the superstitions, sorcery, and burning at the stake of the Catholic Church, the Muslim world was engaged in science, astronomy, medicine, technology, mathematics, surveying, cartography, and advanced techniques of farming. But most of all, they had been responsible for acquiring, preserving and translating the great knowledge of Greece and Rome. In fact, it is the contention of this carefully researched and densely written book that the West had acquired most of its knowledge of those ancient worlds through documents, libraries and cultural interactions with the Arabs who had preserved, collated and translated most of the texts of antiquity that later came into the hands of the West.

It is a contentious thesis that is not only very plausible, but also well-documented. For me it was the eyeopener I was expecting to find by reading Arab authors, however what I found among Arab authors was disappointing. Not so here, Jonathan Lyons, an Aussie, has “done the research” and set the history of that period up right again.