Meet the Censored: Abigail Shrier

Where is the line between boycott-based activism and corporate censorship?

Abigail Shrier of the Wall Street Journal has been in the middle of two major international news stories in the last year. One involves transgender issues. The other, the subject of this article, is about censorship.

The history of campaigns to suppress books in pre-Internet America is not littered with successes. Techniques ran the gamut, from school systems pulling The Catcher in the Rye, Catch-22, and Toni Morrisson’s Song of Solomon, to parent-led campaigns against individual schools teaching The Color Purple, to libraries removing A Clockwork Orange, to the U.S. Postal Service declaring For Whom the Bell Tolls “un-mailable,” to the firing of a teacher who assigned One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, to dozens of other episodes.

Most such efforts failed. The typical narrative involved a local conservative or religious group arrayed against national publishers and distributors, although there were instances of campaigns instigated from the other political direction (e.g. calls to ban or boycott books like To Kill a Mockingbird and American Psycho for offensive portrayals of women and minorities). These efforts however were usually opposed by a consensus of intellectuals in politics, media, and academia, all of whom tended to be institutionally committed to speech rights.

The increasingly concentrated nature of digital media, combined with changing attitudes within the intellectual class, has reversed the geography of speech controversies. Campaigns against books now begin at universities, newsrooms, and the offices of companies like Amazon and Google, and have success; anti-censorship campaigns tend to be disorganized and poorly funded, and fail.

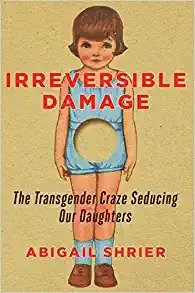

No book exemplifies these new dynamics more than Shrier’s Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters. The book grew out of a news phenomenon that began to be reported years ago: a seeming surge in young girls seeking gender affirmation therapy. In Britain, the National Health Service reported a 4000% rise in such cases, prompting the government to order an investigation into “why this is and what are the long-term impacts.” There were similar reports in other countries, with Sweden’s health officials reporting a 1500% rise, and doctors in the U.S. reporting a four-fold rise in girls receiving transition surgery in 2016 and 2017.

Some hypothesized that the rise was simply due to increased acceptance, while others wondered if there were unknown cultural or psychological factors in play. One of the first efforts to look at the question scientifically involved a controversial survey by Brown University researcher Lisa Littman, who did a study involving 256 parent reports of children who’d discovered transgender identity for the first time during adolescence.

Shrier’s book is based on Littman’s study, which hypothesizes a theory (stressing the words hypothesize and theory) called Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria. In ROGD, adolescent girls who’d not previously shown symptoms of dysphoria discover trans identities in clusters, ostensibly as a result of peer pressure from friend groups, social media, and other avenues. This unfortunately named “contagion” theory compares such clusters to similar groups in cases of girls suffering from anorexia or other eating disorders, but Littman stops short of making definite conclusions, saying ROGD had “not yet been clinically validated” and “more research… is needed.”

Building around the stories of some of the parents in Littman’s study, Shrier employs more aggressive rhetoric. She takes aim at a host of institutional actors, from school administrators who adopt policies of lying to parents, to therapists and psychiatric associations who seem to prioritize affirming over assessing, to medical professionals “rubber-stamping” transitions, perhaps out of fear of being labeled transphobes.

Shrier openly writes from the perspective of someone new to a lot of the issues she’s covering. When she recounts the experience of a friend whose trip to Nordstrom’s for her 13-year-old daughter’s first bra fitting went “badly,” the reader learns that the “problem” was a lingerie specialist who was “six feet tall, pancake makeup blurring a stubbled jaw, two breasts grafted on to a muscular torso like add-ons… no mistaking… male.” She goes on to note, “My friend’s reaction… was utterly standard for women of my generation. But it is also quickly becoming outdated.” The friend’s daughter, she pointed out, thought nothing of it.

Passages like this raise the question of whether Shrier’s book is just the same “outdated” response to the “epidemic” of young girls seeking to transition. At times in the text, she herself seems worried this might be the case. Is she describing a problem that isn’t there? At least with regard to the subgroup of girls of the type Littman studied, she insists not, and makes arguments that are persuasive. One issue is intimidation: how can science properly assess certain therapies if people like Littman, Toronto-based Dr. Kenneth Zucker, and multiple others are losing jobs and academic appointments for asking the wrong questions? Another is a medical system financially incentivized to move patients through expensive courses of treatment and surgery. “I long ago stopped trying to totally understand this,” she’s told by one surgeon, who by then had performed over 1,000 top surgeries.

Overall, she argues that society has built a bureaucracy that in accepting certain views of transgender identity is over-encouraging children into potentially “irreversible” decisions at an early age, like for instance taking puberty blocking medication.

The counter-argument is that those concerned about the “irreversible” effects of puberty blockers should consider that the alternative path might contain equally irreversible effects, because “endogenous puberty is non-consensual for the youth,” as the Empowered Trans Woman blog put it last week. Essentially, this is the debate: the likes of Shrier and Littman argue some adolescents and teens might be too young or too damaged by trauma, depression, OCD, or other factors to be encouraged into potentially life-changing therapies, while trans activists warn that failure to treat carries equally dire and irreversible consequences, while risks of treatment are minimal.

Probably part of what triggers progressives about Shrier’s book — Glenn Greenwald pointed this out in a Substack piece about the ACLU response to her — is its tone and title, reminiscent of conservative tropes about the corrupting influence of everything from pornography to heavy metal to the occult (How Satan is Seducing Our Children being just one example). However, the book also recalls another genre, the debunking or deconstruction of a popular intellectual trend, a la The Myth of Repressed Memory. That type of book is often hard to get published and initially misunderstood, while also incurring considerable backlash. Sorting out whether this book is the former or the latter, reaction or investigation, is normally what a public debate is for. That mostly didn’t happen in this case, as the entire issue was declared taboo, with the people most associated with the subject earning professional consequences.

Littman lost a consulting job, while Brown took down a link to her study, and the peer-reviewed journal in which she’d published, PLOS One, issued a highly unusual “correction.” The correction didn’t actually correct anything but merely underscored that Littman’s was a “descriptive, exploratory study” that relied entirely on parent reports for data, noting that there were things “parents would not have access to.” On the other hand, some 4000 academics signed a petition criticizing Brown and PLOS One for not standing up for Littman, with a common sentiment being, “If it’s wrong, let someone produce evidence that it’s wrong.”

A number of mainstream writers wanted to review Shrier’s book, but were turned down by editors, to the point where even Kirkus, which reviews everything with a cover on it, wouldn’t go near. When Shrier appeared on The Joe Rogan Experience to discuss the book, it sparked a chain of events that led to an uprising at Spotify, which now hosts the Rogan show. Executives there held no fewer than 10 meetings with employees demanding that the “transphobic” episode be taken down. Amazon refused to run ads by Regenery, Shrier’s publisher, and digital options for the book were sufficiently closed off that some parent groups were reduced to raising money on GoFundMe to put up billboards promoting Shrier’s work — until GoFundMe took down those campaigns, too.

Shrier became the poster child for the “ick factor” phenomenon, in which a person at the center of an Internet controversy is denounced often enough and in furious enough language that people with jobs and reputations to protect soon find themselves unwilling to risk even a neutral association online, not wanting to get the ick of public displeasure on them. If interviewing Shrier can become this big of a headache for someone with a $100 million deal, like Rogan, how many journalists with less job security (i.e. all of them) will go anywhere near her book? In the short term, episodes like this go a long way toward convincing conservatives especially that Silicon Valley is bent on politicizing the digital marketplace. It’s worth noting that the Streisand effect has been powerful here, with conservative coverage of attempts to suppress the book driving sales higher and higher, to the point where it’s the #1 seller on Amazon’s list of LGBTQ books, surely not what Amazon had in mind when it banned ads for the book.

The liberal position once was that unwelcome speech was either ignored or challenged by better speech, but this has been abandoned in favor of a politics that embraces making use of technology and extreme market concentration to suppress discussion of whole topics. This is the inverse of old campaigns against unpopular ideas: instead of rogue school boards in Dayton, Tennessee or Dover, Pennsylvania declaring subjects off-limits, it’s more powerful committees with national or international reach at Target or GoFundMe or Google AdSense.

Just recently, a British High Court judges ruled against the Tavistock Centre, which runs the country’s only gender-identity development service. The judges addressed issues in Shrier’s book, saying, “It is doubtful that a child aged 14 or 15 could understand and weigh the long-term risks and consequences of the administration of puberty blockers.” The decision came in the wake of a string of whistleblower-driven news stories in the U.K. about concern among some staff at Tavistock about the possible over-prescription of puberty blockers. Some resigning clinicians for instance worried treatment amounted to “conversion therapy” for some gay children, who may have been reacting to homophobia at home.

Is it possible the judges ruled incorrectly? Is it possible the High Court didn’t listen enough to all of their witnesses (one for instance testified that puberty blockers “may have saved my life”) or were guided by an incomplete understanding of the challenges faced by trans children? Absolutely.

The Tavistock decision however shows there’s enough controversy even among scientists and the people who work most closely with trans children that the contours of the debate at least have to be reported. In other words, the issue for sure passes the smell test as a news story, if not as science. In the U.S., though, the issue has essentially been driven out of mainstream coverage, at a time when people are losing the ability to distinguish between endorsing every idea in a study or book, and endorsing their right to be published and discussed.

Is what happened to Shrier just an example of effective boycott-based activism, or is this a new form of censorship? TK asked her to elaborate:

TK: Is the recent High Court decision in Britain related to the subject matter of your book? Do you feel that it vindicates your reporting?

AS: Absolutely. The High Court came to the conclusion that a substantial number of the young people who are proceeding with medical transition, under the current ‘affirmation’ regime, are going to be making a mistake. And that’s all I’m concerned about. There are going to be a lot of unnecessary medical transitions and unnecessary transitions are irreversible damage.

I think it’s hard to read the court’s ruling and not see that. The gender clinic in Great Britain – exactly like those in the United States – was proceeding with medical transition based on a young person’s own recognizance. This is “affirmative care”: the young person decides she has “gender dysphoria,” the doctors are instructed to agree with this diagnosis and proceed with medical transition. And the court decided that when the risks are things like infertility, these are things young teens can’t properly appreciate. Good medical judgment must often intervene in the rash decisions of adolescents, and that’s not happening in these cases.

The court noted that no adolescent who presented at the clinic was turned away on the basis that she couldn’t give informed consent. That sounded fishy to the court, and they were shrewd to point it out. It’s simply implausible that every last teen passed the threshold for informed consent. In what other area of medicine does no one get turned away? What it suggests is that there aren’t medical professionals who are intercepting the Keira Bells of this world before they undergo unnecessary gender surgeries. There are no safeguards for those young women who are not ultimately going to be helped by this process. In a nutshell, that’s the thesis of my book.

TK: Your book has inspired a range of responses, from what feels like an informal editorial blackout to GoFundMe disallowing fundraising campaigns to publicize your work, to Amazon refusing to run your publisher’s ads. Which do you feel is merely annoying, and which is genuinely out of bounds? In other words, where do you feel the line is between legitimate activism, and corporate censorship?

AS: At the very least, corporate censorship is illegitimate when it’s a betrayal of the mission of the organization. If I go into a left-wing book shop and they’ve chosen not to carry my book, that’s fine. But Amazon calls itself the “world’s largest bookstore.” It has no editorial mission that would justify blocking my publisher’s ads. Its mission is to carry the most books and serve the reading public. And it’s a severe corruption of Target and GoFundMe, similarly, to decide that the only books or fundraisers it hosts are ones that support woke-approved ideas. (GoFundMe boasts that it’s “on a mission to help people fundraise for personal, business and charitable causes.”)

Kirkus claims to review 10,000 books per year, including self-published titles, the purpose of which is to inform the public about new books and highlight (“star”) the ones it deems worthwhile. When Kirkus silently ignores a major publication, indeed a best-seller, as it did mine, it’s violating its own mission. That’s corruption.

TK: You wrote in Quillette: “This is what censorship looks like in 21st-century America. It isn’t the government sending police to your home. It’s Silicon Valley oligopolists implementing blackouts… while sending disfavored ideas down memory holes.” Where are traditional institutional defenders of free speech like the ACLU on this new form of censorship you describe? How about other working reporters?

AS: A top lawyer at the ACLU called my book “dangerous” and declared on Twitter: “We have to fight these ideas which are leading to the criminalization of trans life again.” He also wrote: “Also stopping the circulation of this book and these ideas is 100% a hill I will die on.”

This is a complete corruption of the ACLU’s mission. The ACLU has traditionally opposed not only government suppression of speech, in violation of the First Amendment, but also corporate censorship. As ACLU staff attorney Vera Eidelman wrote on the ACLU blog, in a July 20, 2018 post entitled “Facebook Shouldn’t Censor Offensive Speech”:

“What's at stake here is the ability of one platform that serves as a forum for the speech of billions of people to use its enormous power to censor speech on the basis of its own determinations of what is true, what is hateful, and what is offensive. Given Facebook’s nearly unparalleled status as a forum for political speech and debate, it should not take down anything but unlawful speech, like incitement to violence.”

So that fact that, in practice, at least one prominent lawyer at the ACLU has decided that book banning by Target is only offensive when it pertains to books he likes—that’s a real betrayal of its mission and the public trust. No one at the ACLU denounced or disclaimed his opinion.

A lot of working reporters were upset about an ACLU lawyer calling for my book to be banned. But I also think it’s worth noting that almost all the liberals upset by this have one thing in common: they are older than millennials.

TK: Spotify executives have reportedly had upwards of 10 meetings to discuss whether or not to remove your interview with Joe Rogan from its archive. Have you had any contact with Spotify yourself? With the protesting employees? How important is it that they not give in, and why?

AS: I haven’t had any contact with Spotify or with the employees. Joe Rogan has been very firm, as has Spotify, that it will not grant its employees an editorial veto over the content of the platform. It’s a really important development, I think. As Churchill said after an important British military victory, “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” I think that might be said of today’s war against Cancel Culture. Spotify is a technology firm and the fact that it has held firm against the complaints of woke employees – that may just signal the end of the beginning.

TK: Do you think what happened with your book, in terms of the problems with digital promotion and distribution, will have an impact on book publishers? Will they stay away from controversial topics? You say you haven’t been harmed and will write more books, but has this experience made that harder?

AS: Publishers are already shying away from controversial topics. I’ve known so many authors who’ve tried to write anything to do with gender ideology and been dropped by their publishers or otherwise shut out. So, yes, they’re already staying away from controversial topics. In other words, the areas of American life in most dire need of investigation are precisely the areas that have been declared off-limits.

This is why the current medical scandal of poor health care for trans-identified teenagers persists. It’s because no one is allowed to weigh risks and benefits. No one is allowed to question basic medical protocols. This is an area of experimental medicine where scientists and doctors should be taking a hard look at the protocols to ensure that those susceptible to regret do not undergo irreversible procedures. And yet, instead, we’re so busy congratulating and celebrating medical transition for young people who trans identify, that we’re practically guaranteeing that many of them will regret their choices.

TK: What would you say to someone who is politically progressive and isn’t concerned by that “21st century America” version of censorship you describe? Why should that person care?

AS: We can have different beliefs about all kinds of political issues—environmental policy, abortion, nationalized healthcare—and those disagreements are proof of a healthy democratic society. But the foundation of civil society is a meta commitment to free speech. We must be able to discuss our differences openly. Once you decide your political commitment is more important than maintaining free inquiry, society gets very dark awfully quickly—with highly unpredictable results.

I think, sometimes, people imagine that if they shut down discussion of the risks and benefits of medical transition for teenagers, they’ll get their way. But it doesn’t work like that. The result of suppressed discussion could involve a very irrational and counter-productive backlash. The lesson of McCarthyism wasn’t: ‘Don’t blacklist Leftists,’ it was: ‘Don’t blacklist Americans.’ If we can’t agree on that, the foundations of civil society will crumble.

This post is only for paying subscribers of TK News by Matt Taibbi, but it’s ok to forward every once in a while.

ROBERT STEELE: I subscribe to only two people in this planet: Matt Taibbi and Ben Fulford. I follow Martin Armstrong, Charles Hugh Smith, Ron Paul, and a few others and am blessed by my network of intelligent fans who feed me stuff they know will be of interest to the Phi Beta Iota collective.

ROBERT STEELE: I subscribe to only two people in this planet: Matt Taibbi and Ben Fulford. I follow Martin Armstrong, Charles Hugh Smith, Ron Paul, and a few others and am blessed by my network of intelligent fans who feed me stuff they know will be of interest to the Phi Beta Iota collective.