Below is a very interesting summary of the political tensions among secularism and religion and modernism and tradition in Tunisia. I think the author, who I do not know but whose writings I have followed, is one of the most knowledgeable observers of the Arab Spring.

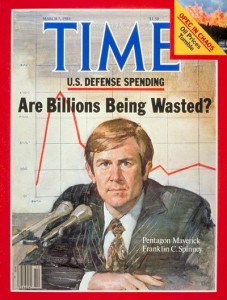

Chuck Spinney

Washington Report on Middle East Affairs

April 2013, Pages 41-42

By Esam Al-Amin

THE SPARK THAT ignited the Arab Spring over two years ago came from Sidi Bouzid in Tunisia. For 28 days people across the country revolted against the repression and corruption of the 23-year authoritarian regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Finally, on Jan. 14, 2011 Tunisians celebrated their victory and resilience over tyranny and oppression when Ben Ali fled the country. But if getting rid of the dictator was relatively short and easy, the dismantling of his regime and its corrosive effects on society has proven to be very challenging indeed.

Tunisia possessed several advantages over other Arab countries experiencing revolutionary change since 2011. Compared to Egypt, it is a relatively small country of 11 million, with a homogeneous population and a highly literate public. In the half-century since its independence from France in 1956, Tunisian society was able to recover from its three-quarter-century colonial past, reclaiming its Arab and Islamic heritage by establishing strong political parties and popular social movements based on Arab nationalism and Islamic ideology.

But even as secularism and liberalism maintain a distinct presence in Tunisian society, as well as being rooted among the elites and in urban areas, religious traditions and practice are strongly embedded throughout the country and across all classes, particularly among the poor and the middle class. In addition, the Islamic movement led by the Ennahda (Renaissance) Party represents one of the most religiously moderate and modern political Islamist trends in the Arab and Islamic world. Its outlook on modernity and the relationship between state and society is similar to the Justice and Development Party in Turkey. Ennahda’s leader, Sheikh Rachid al-Ghannouchi, is also considered one of the most modernist Islamic thinkers, who readily accepts the concept of the modern democratic state with all its nuances and limitations.

As the political party that suffered through the most repressive measures carried out by the former regime’s security forces for more than two decades, Ennahda unsurprisingly won a plurality in the October 2011 elections, capturing 42 percent of the vote and becoming the country’s majority party, with 89 of 217 seats in the Constituent Assembly. Within weeks of the elections, Ennahda formed a coalition with two other secular and leftist parties, namely, the Congress for the Republic, led by human rights activist Moncef Marzouki, and the Bloc for Labor and Liberties, led by legendary leftist Mustafa Bin Jaafar. While Ennahda retained the post of prime minister, to be occupied by its general secretary, Hamadi Jebali, it backed Marzouki as president and Bin Jafaar as parliamentary speaker. The main loser in the elections was a coalition of 11 rigidly anti-Islamist secular parties and former communists under the name of Democratic Modernist Pole, which garnered no more than five seats in the Assembly.

Thus, by the end of the first year after Ben Ali’s overthrow, Ennahda and its coalition partners were in firm control of the Tunisian political scene. Their one-year mandate was to lead the transitional period by writing a new constitution, stabilizing the economy, purging the state bureaucracy of the corrupt elements of the former regime, and preparing for new parliamentary elections after the passage of a new constitution.

But despite the great hopes and relative calm of the first year, the following year was marred by bitter political divisions, economic stagnation, and the deterioration of security. On the Islamic front, several conservative Salafist parties were established, challenged Ennahda, and pushed for a more conservative agenda, calling for the inclusion of shariah as the source of legislation in the new constitution.

These calls provoked a bitter debate between the Islamists on one hand, and staunch secularists, liberals and leftists on the other. The frame of the discussion was effectively changed from a “revolutionary vs. counter-revolutionary” political struggle into an “Islamist vs. secularist” ideological battle.

Since the conservative members of Ennahda were drawn into this fight on the side of the Salafists, the debate consumed and drained the country for several months until Ghannouchi and Ennahda’s leadership wisely ended it by siding with the liberal parties and saying they would not include the word shariah in the constitution. Ghannouchi reasoned that lifting the language from the old constitution that “Islam is the religion of the state” was enough to preserve the Islamic identity of Tunisian society. He argued that any mention of shariah would needlessly divide the society, and that Islamic law could not be imposed from above.

Using highly volatile rhetoric, the secularist opposition nevertheless still accused Ennahda of having a secret Islamist agenda, charging that the Islamist party was trying to infiltrate the state and appoint thousands of its members to the most sensitive positions in government. Furthermore, ordinary Tunisians felt that their economic well-being not only failed to improve but had actually worsened, as labor strikes, demonstrations and civil disobedience became more frequent.

In reality, most Tunisians had revolted against the Ben Ali regime not only to end its political repression but to address its economic corruption, poor performance, high unemployment and lack of social justice. But now the corrupt elements of the former regime, currently occupying sensitive positions in the media, intelligence services, security forces and state bureaucracy, have further undermined the coalition government by incessantly attacking Ennahda and its leaders.

In the midst of the tensions caused by charges and counter charges between the Islamists and secularists, who are aided by former regime loyalists, political turmoil in the country escalated when a popular political figure, Chokri Belaid, was assassinated. Belaid was a labor and human rights lawyer and politician who led the left-secular Democratic Patriots’ Movement. He was extremely vocal against political Islam and sharply critical of Ennahda and its leaders. On Feb. 6, he was killed in front of his house by unknown assailants.

Until then, assassinations were unheard of in the political context of Tunisian society. Secular groups quickly accused the Islamists of carrying out the shocking act. All political parties condemned it, as hundreds of thousands participated in Belaid’s massive funeral and protested the horrifying act. Furthermore, four secular and leftist parties withdrew from the Assembly and called for general strikes. Prime Minister Jebali called the killing “a political assassination and the assassination of the Tunisian revolution,” while Ennahda issued a statement calling the attack a “heinous crime” which targeted the “security and stability of Tunisia.”

The immediate political consequence of this incident was a declaration by Jebali on state TV to form a new caretaker government made up of technocrats and professionals. The nation needed to de-escalate the political tensions and focus on the acute political and economic problems facing the country, he stated. While many opposition parties welcomed his announcement, Ennahda rejected it. Ghannouchi warned that a government composed of political parties with a shared agenda and a common program would better guarantee legitimacy and stability. While they both suffered from divisions within their own ranks, resulting in party splits, Ennahda’s two coalition partners initially backed Jebali’s idea—but then withdrew their support in favor of a political government. Their critics charge that the coalition is trying desperately to cling to power after failing to fulfill any of their electoral mandates, from writing a new constitution to overseeing an economic recovery and growth.

On the other hand, Ennahda leaders argue that a new constitution has indeed been drafted that enshrines many rights, freedoms and principles of democratic governance. They bitterly and discreetly complain of foreign interference that aims to undermine the revolution and destabilize the Islamists’ rule. As Jebali resigned and refused to form the next government on the basis of political coalitions, Ennahda chose Interior Minister Ali al-Aridh to form the next government with the same coalition partners. Al-Aridh vowed to form a government composed of all political trends and competent technocrats.

One reason revolutions are so rare in history is that they represent massive popular expressions of discontent and anger with the existing political order built up over decades. Once they reach the tipping point, they result in the toppling of the existing order and establishment of a new one. But the most important principle during the transition period is not the implementation or preservation of democratic norms, based on sharp political and ideological differences, but the preservation of political and social harmony in the country until the old regime is completely eradicated and a new order is established in its place.

The sooner Tunisian leaders of all political strands recognize this fact and focus on the main objectives of the revolution—namely freedom, social and economic justice and human dignity—and postpone their ideological battles until a new order is established, the more likely their remarkable revolution will succeed and endure.

Esam Al-Amin is the author of the newly released book The Arab Awakening Unveiled: Understanding Transformations and Revolutions in the Middle East (Kindle).

He can be contacted at < alamin1919@gmail.com>.