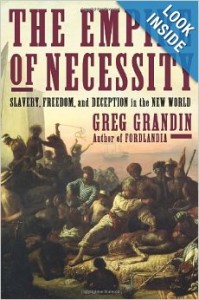

Greg Grandin

![]() The complexity of the moral landscape during America's founding generation, March 2, 2014

The complexity of the moral landscape during America's founding generation, March 2, 2014

The reader is unlikely to find a book that better contextualizes or sharpens the focus of the moral issues confronting America's founding generation than this book. Using the metaphor of “empires of necessity,” the author shows how America's westward expansion made it the advance-guard of the world, beating a path through the wilderness. But America has never acknowledged that it was enslaved peoples who were in fact beating that path called Manifest Destiny: cutting down forests, turning the wilderness into plantations and into marketable real estate, and picking cotton and cutting the sugar cane that drew more and more territory into a thriving atlantic economy. Slavery alone was the issue at the top of the world's agenda throughout the era of the founding of America. The evils of slavery and the slave trade was the constant refrain of sermons each Sunday from Connecticut to Montevideo; and from Seville to London.

This flywheel to Spain's “American market revolution” had started 300 years earlier with the “reconquest,” and had ended with a rash of rebellions against colonial rule begun in South America after the French Revolution had sparked the slave revolt in Haiti. The British colonies got into the act towards the very tail end. Pirating was the number one instrumentality of global trade and thus of slavery. But it was not the free-wheeling buccaneer-spirited enterprise we have been taught and have seen our movies rhapsodize about. Instead, under Spanish tutelage, for more than three centuries, it was a “well-regulated business.” During this period, when pirates were members of a guild, the better part of twelve and a half million slaves had been captured and hauled across the Atlantic in unspeakable conditions, all while the American Revolution was in full progress.

At the height of Spain's unchallenged rule of the seas, where nothing moved on the open ocean without a Spanish stamp, the English colonies were considered just a piss-ant irritant on the margins of Spain's vast Christian Empire. And as the narrative here shows, slavery served as context, subtext and all of the punctuation marks for a sprawling historical narrative that takes place just as the sun finally begins to set on the 300-year old Spanish monopoly of trade on the high seas. The irony amongst all ironies is that the age of Colonial America's liberty was also the most brutal age of slavery. The two were like two peas in a pod. In Colonial America, liberty for some, by definition, meant bondage for others, especially in the southern part of the U.S. as the South caught the Spanish “slavery fever” with a vengeance.

In one of the most famous slave insurrections on the high seas, this book tells the story of how one group of 80 desperate slaves, took over the slave ship “Tryal.” The rebels killed the white crew except for the Captain, who was saved to be used as part of a negotiating ruse designed to gain them their final inch of freedom. Amasa Delano, the American pirate who eventually came to the ship's rescue (and was the butt of the ruse), was forced to recapture the ship when the white captain managed to free himself and jumped ship, exposing the ruse. The rebels were then quickly rounded up and turned over to Spanish authorities who hanged them and impaled their leaders' heads on stakes in the town center.

The foreground is a narrative about how Amasa Delano happened upon the aimless ship that he first rescued and then was forced to attack and recapture. The background and the subtext, is about how “the age of liberty” also became “the most savage age of slavery;” and how slavery, under the tight control of the Spanish Crown, invented and then corrupted the world of seafaring commerce. And while the author did not set out to do so, this book, in relief, tells beautifully the story of how the Atlantic trade in slaves corrupted the one nation of white men, themselves suing for liberty and freedom from their own colonial masters, paradoxically remained a nation tone-deaf to the cries of freedom from their own black slaves? Obviously, as even American text books now slowly begin to show, they were much too busy themselves personally engaging in the fruits of that ruthless, sordid, brutal, and inhuman business of enslaving others.

Almost to a man, America's founding fathers had all been so thoroughly corrupted and morally compromised by their own personal involvement in the sordid slave business, that in those trying days of Philadelphia, they all were effectively reduced to the world's best known “hypocrites of freedom.” Which goes a long way towards explaining one of the questions that has always perplexed me: Why it is that the French Revolution, even though it occurred a decade later than the American Revolution, is still the revolution held up by freedom-seeking and freedom-loving people around the world as the ultimate symbol of liberty?

More to this point, even as the Fascists stalked the globe in the run up to WW-II, it was the Bolshevik Revolution, and not the American revolution, that caught the attention of, and won the hearts and inspired freedom-seeking people across the globe, including many Americans and British to its cause? Except for America's own “fair-weather pseudo-patriots,” rarely is the “slave-tainted American revolution” held up by freedom-loving people as the symbol of freedom and liberty? Surely it had something to do with the fact that even when slaves joined the colonial army, they still were denied their freedom. While their British opposition, granted the slaves their freedom as an immediate condition of military service. The readers surely recall the eloquent defense by John Quincy Adams of a similar crew of 53 Africans on the Amistad. They were freed before the American Supreme Court. However, less than a decade later, the U.S. Congress enacted the draconian “Fugitive Slave Act, ” which threw the American Revolution into reverse. It basically said that property and preservation of the Union were higher values than freeing slaves?

Another question this book raises is that of whether Hermann Melville's “Benito Cereno,” a fictionalized account of this insurrection, by emphasizing the deviousness of the rebel's ruse — to the exclusion of the larger issue of “slaves fighting for their own freedom” — was intended merely as pretext and as a special plea for the pro-slavery cause?

While the author artfully dodges the issue of Melville's motives, no one can dodge the fact that there were so many issues — all enabled by slavery — that shook the very moral foundation of those revolutionary times, that it is difficult NOT to see the glaring moral contradictions that slavery represented to the American Revolution? Slavery had it own moral collateral damage, for in addition to the brutality and evils of slavery itself, there also was the crime and lawlessness of piracy raging on the high seas, the depletion of seals and whales and the general exploitation of the marine ecology for economic gain, plus the permanent debasement of peoples raised in a hateful race-based slave society where structural inequality was the built-in cross-generational consequence. In retrospect, it seems not only immoral, but also short-sighted and dumb to have build a revolution entirely off the backs of slaves — which is to say, one based only on the wealth derived from morally questionable forms of economic exploitation, and then call such a revolution a revolution based on “freedom” and “liberty?”

Much to his credit, rather than debate the merits of the moral basis of the American Revolution, the author keeps the reader's eye on the ball by carefully leading us through the many thickets and mind fields of moral complexity. Yet, when he comes out on the other side of the Andes, this well-researched, sophisticated, nuanced and carefully choreographed narrative, nails down every moral issue relevant to the context of America's founding generation. It is then left up to us, the reader, to sort things out and decide for ourselves just what the truth really is? And for me, I believe it is impossible for anyone to remain confused about what our founding fathers were up to during those trying days in Philadelphia? Quite simply, they were defending the freedom to exploitation on the high seas, including to continue engaging in trading in human lives. And every man in Constitution Hall was acutely aware of the consequences of what they were doing, period.

As an aside, this author's careful, probing, and his expert analysis, calls to my attention the wonderfully famous but much more heavy-handed probing in the book by Charles Beard, called “An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States,” in which Beard too makes the parallel claim that the founding father's notion of “freedom” and “liberty,” was thoroughly tainted by a dense background and subtext of immorality driven by corruption, greed, in-fighting, land speculation, the brutality of slavery, squandering of nature's resources, and the mindless pursuit of profits both on land as well as on the high seas.

it is worth mentioning too that there are at least three other contemporary books that come to the same conclusions as did Grandin and Beard about the meaning of the American notion of freedom and liberty. See for instance, Peter Andreas', “Smugger Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America;” Benjamin Woolley's “Savage Kingdom: The True Story of Jamestown 1607 and the Settlement of America;” and finally, Andrea Stuart's “Sugar in the blood: A Family's story of Slavery and Empire.” I have reviewed them all on amazon.com.

In the present book's much richer, fact-based context, the author does not take sides. To him it apparently seemed a lot easier to allow the facts to lead the reader to his own discoveries of how and why our founding fathers would turn a blind eye and a deaf ear away from the staggering suffering of their own slaves, and towards a more clinical business oriented transactional notion of their own “white male only” freedom?

Indeed, it seems all but clear in retrospect that what they meant by “freedom” and “liberty” was simply the transactional ideas of: “freedom of the seas,” “freedom of commerce,” and thus the freedom for white men like themselves to engage in unfettered trade, trade that invariably involved crime, violence, social dislocation, destruction of the environment, general mayhem, and last but certainly not least, the buying and selling of other unfree peoples? This “transactional notion” of freedom, with all of its attendant unwritten conditions, goes a long way towards explaining why the American Revolution did not have the same cachet as the French (or even the Russian) Revolution.

For sure, the most astonishing insight that comes from reading this book is not just the revelations about America's “transactional idea of freedom,” but that the more one learns about the American revolutionary generation itself, the more one is forced to appreciate the profound influence on U.S. history that the 300-year era of unchallenged Spanish rule has had in shaping America. To underscore this point, in the epilogue, the author points to a rather astonishing article in the “Augusta Daily Constitutionalist,” in 1859, which implored Georgians to build their own “slave Empire,” extending from San Diego, on the Pacific Ocean, along the shore line of Mexico across Central America to the Atlantic. Ten stars!